A patient enters a Texas teaching hospital and under supervision, a nursing student starts the patient’s IV. The patient’s significant other doesn’t like that she is in discomfort. He pulls a knife out of his pocket and threatens the fresh-faced nursing student. Although this was the first instance of hospital workplace violence endured by Rhonda Collins during her honorable nursing career, it certainly wasn’t the last.

“I’ve been punched, I’ve been bit — I’ve had all of those incidents happen over the years,” Collins said in an interview with Campus Safety. “I look back and we all were just like, ‘Well, that’s just our patient and that’s what we do.'”

Therein lies part of the problem, Collins says: nurses rationalizing violent patient behavior.

“There’s no other profession in the world where you got to work and go, ‘Well, if my customer bites me or punches me, that’s just part of the job.’ That doesn’t happen anywhere except in healthcare,” she continued. “However, I’m grateful to see that the conversation is changing. We’ve really got to talk about changing the culture of how we approach this.”

Collins poses for a photo with the child of a friend she helped deliver when she was a labor and delivery nurse.

Now, more than ever, it is essential that the conversation changes since a recent survey from the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) found hospital assaults hit an all-time high in 2020. From 2019 to 2020, the assault rate at U.S. hospitals increased more than 23%.

Collins has seen innumerous instances of violence against nurses in her many roles within the healthcare industry. She started as a labor and delivery nurse, making her way from unit manager to director of women’s services, and eventually to vice president of nursing at one of the largest hospitals in the United States. Life circumstances and the need for a more traditional work schedule led Collins into healthcare industry, where she was pleasantly surprised to quickly learn she could make real change in nurse safety. She is currently the chief nursing officer for Vocera, which provides communication products and services for healthcare employees.

During her various roles throughout the years, Collins has seen ebbs and flows in hospital workplace violence that often reflect the pulse of the country as a whole. Nearly two years into a global pandemic and a politically divided country, Collins said it’s the worst she’s ever seen it.

“I truly believe our next pandemic is mental illness because we have seen such an exacerbation of anger, just a fury that consumes our country right now from every direction and that definitely spills over into the hospital environment,” she said. “Children have been separated from their social infrastructure of schools and adults have been separated from their social infrastructure at work. When you think about taking one of your children or your husband to the hospital and then being told that you can’t be in their room and how that would make you feel, even though we did it for good reason, it’s created an ethical situation that we have to address on the backside as leaders in healthcare.”

At the start of the pandemic, nurses and other healthcare workers were praised for their dedication and for risking their lives to fight a disease that health officials knew little about. However, the tables have turned. Many hospitals are now reporting that respect and admiration have been replaced with violence and anger. Collins recalled a recent incident in her area where a nurse who had just gotten off her shift and was still in her scrubs was getting gas when a man started screaming obscenities at her and threw hot coffee on her.

“I follow several nurse groups on social media, and they’re all saying, ‘Take care of yourselves out there,’ and ‘Don’t wear your scrubs to work — don’t wear them out of the hospital or identify yourself as a healthcare worker.’ I had one nurse say to me, ‘I never thought when I went into nursing that every night when I would drive to work, I would think, ‘Is this the night I won’t go home?'” Collins said woefully. “I do think it just reflects the general boiling undercurrent of the country. It just bleeds over into everything, and it’s created a situation where healthcare leaders have to reevaluate how we deal with it.”

On the bright side, one good thing to come out of the pandemic, said Collins, is that it has moved the nurse from the bedside into a seat of authority since they are the ones confronting this disease head-on.

“It’s no longer people who are behind closed doors in the boardroom making decisions — it is those people who are doing the work day in and day out, and we have to listen to what they have to bring to the table,” she said. “They are the experts, and you can watch them work and see that they know exactly what to expect in the moment that it can happen.”

What Needs to Change to Mitigate Hospital Workplace Violence?

While there is no one solution to this growing problem, Collins believes the number one thing that has to change is the culture surrounding reporting violent incidents. Too many nurses look the other way, she says, and make excuses for their patients or each other.

“There is a culture among nurses that ‘You’re not strong enough if you react to someone being aggressive towards you.’ We have to aggressively tear down the culture that has allowed that to flourish, and we have to address it,” Collins urged. “We have to create an environment where nurses can freely and safely report incidents that happen to them.”

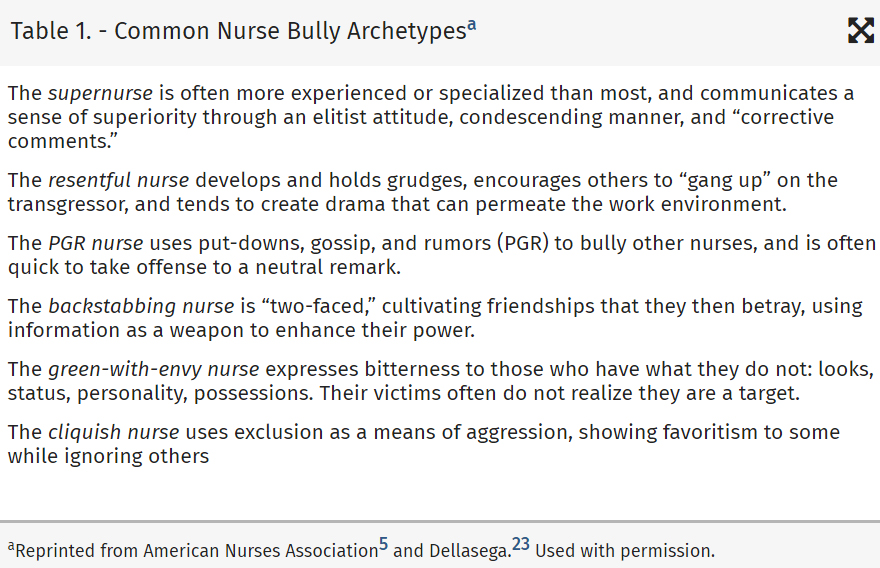

The more unknown threat of nurse-on-nurse bullying is also something that needs to be addressed within nurse culture, says Collins. Typically referred to as lateral violence, bullying amongst nurses is a common occurrence. According to the Workplace Bullying Institute, an organization dedicated to the eradication of workplace bullying, 36% of all complaint calls are from nurses, making them the most frequent callers. In fact, one study found that within the first six months, 60% of nurses leave their first job due to the behavior of their coworkers.

“It’s the nurses-eat-their-young conversation. It’s been going on for decades. It’s a stressful environment, and it’s a competitive environment,” Collins described. “There’s the good nurse, the nurse who’s not as good. Just like all human environments, human behaviors are exacerbated under stress. You pressure cook it, and people’s tendencies come out.”

Examples of nurse bullying (Source: Nursing Administration Quarterly)

In another study, over 50% of nursing students reported seeing or experiencing nurse-on-nurse bullying during their clinical rotations. However, nurse bullying isn’t only experienced by young nurses. A third study found that bullying occurs at all levels within the healthcare industry, with 60% of nurse managers, directors, and executives reporting they experienced bullying in the workplace.

While the industry is focused on solving the problem and there is less tolerance for the behavior, Collins beseeches experienced nurses to step up and be willing to teach incoming nurses who are joining the force during one of the worst nursing shortages in modern history.

“We have nurses who have spent the last year-and-a-half to two years not allowed into the hospital to do their clinical through nursing school. They’re coming out of nursing school having done everything in a virtual environment or having done everything in a simulated environment. For the first time ever, they’ve got a nursing degree and they’re licensed by the state board, but they’re now just touching patients for the first time,” she said concerningly. “Nurses are also stressed — they’re tired, they’re worn out. They are carrying their own issues from their own personal lives, and sometimes their responses are inappropriate or can be aggressive. Hospitals have to be willing to address that too so they can calm the dynamics of the staff with each other within the hospital.”

To take big steps towards mitigating hospital workplace violence, Collins challenges nurses to “air out their dirty laundry,” and be willing to talk about what they are struggling with and willing to report it — whether it’s outside violence or lateral violence.

“The quality of life for individuals working in a hospital affects the patient, the family, and most especially, our staffs. It should be a reportable measure of what we’re doing to solve for workplace violence, what we’ve done to put in place. If you look at hospitals across the country, it’s very inconsistent. Usually when a hospital has been aggressive about it, they’ve had an event in their area that really drove them to look for solutions so they can prevent it from ever happening again,” she said. “I will say it again: We have to intentionally dismantle what has allowed us to get here — to be tolerant of it or to look the other way. That means we have to take a scalpel to it. We have to open it up and have the very uncomfortable conversation about what we do to change our culture.”

Policies and Procedures Further Supported by Technologies

In order for these desired cultural changes to flourish, they must be backed by healthcare policies and procedures. For some hospitals, a near zero-tolerance policy for both external and internal violence has been implemented to protect staff. One hospital, recalled Collins, ‘fired’ a patient for his repeated violence against nurses.

“The hospital went through their legal systems and their legal roles, and they determined that this patient was a threat to everyone in the hospital and discharged him and said he was never welcomed back,” she said. “Hospitals are taking extreme measures to protect their staff now. That was the first time I had ever heard of that, but I think hospitals have to look and say, ‘What is the benefit of protecting my staff versus allowing this behavior to continue from an outside source?’ When I say we have to aggressively address our culture of going, ‘Well, that’s just what we do,’ we have to aggressively protect the staff.”

While having ironclad policies and procedures in place to protect hospital staff is essential, Collins urgently stresses the need for technologies that supplement those practices.

“I think policies are written words on paper that we all agree in a cooperative, collective community to follow, but sometimes we have to hardwire behavior with technologies that require them to respond in a certain way,” she said.

One such technology is personal mobile duress buttons. “I can’t tell you how many patients’ rooms I’ve been in where the urgent call thing is on this wall over here and I’m over there, right? It’s very difficult to rely on that and having something on your body is always the preferred way to reach out,” Collins said passionately. “Unfortunately, we’ve had nurses lose their lives in trying to care for their patient and just couldn’t reach for help. Their only tool was to yell, and so a lot of times that’s what nurses end up doing — just yelling for help.”

Collins is also a proponent for technologies that simplify nurses’ day-to-day operations — not just technologies that are used for emergency purposes. Allowing technology to carry memory for them enables healthcare employees to focus on other important tasks at hand and to be more aware of their surroundings.

“When I talk to nurse executives, I say, pick the top three or four things that create a congested, chaotic work environment. Can you relieve it with technology? Can you give them a tool? Can you relieve it with a policy or procedure or both a policy, procedure and technology? What can you do to smooth out that particular workflow that frustrates, congests and causes people to act out? And then move forward with it,” Collins said. “I think the focus has to be on equipping these people to hardwire human behavior to allow technologies to carry memory for them — just like you use your smartphone to remember your day for you. Very few nurses get to use those kinds of readily available technologies.”

Collins also urges hospitals to “get outside their own echo chamber” and look at other businesses in the corporate world that have solved communication and workflow issues using technologies. Communication is the very foundation of effective healthcare, said Collins: communication between the family and the patient, the patient and the healthcare providers, the healthcare providers and the extended teams.

During a recent hospital stay as a patient, Collins recollected how with each new nurse or healthcare provider who came into her room, she had to update each of them on her own condition and treatment. Essentially, she experienced firsthand how lack of communication, which can often be remedied by technology, can lead to frustration for both the healthcare provider and the patient, creating the potential for a hostile environment.

For many hospitals, disparate communication technologies that only connect to a limited number of people within a facility are commonplace. In her time with Vocera, much of Collins’ research has been on understanding what causes physicians and nurses to adopt technology and what causes them to abandon it.

“The hospital I was at, nurses were carrying a walkie-talkie to communicate with the emergency department, they had a little ear thing that they had to press a button to talk to only the three of four people within their little unit, and then they were carrying a phone and the residents were carrying pagers. Every single nurse was just loaded down with this stuff, and all that would require is a communication strategy — a real strategy to determine how many different problems do I need to solve,” Collins said. “When you’re working with that many disparate communication tools that don’t integrate or interface with each other, that problem can be easily solved. It doesn’t matter how sophisticated or how important it is or how useful we think it might be if it doesn’t solve the problem. If it doesn’t fit within the context of their work, they quickly abandon it.”

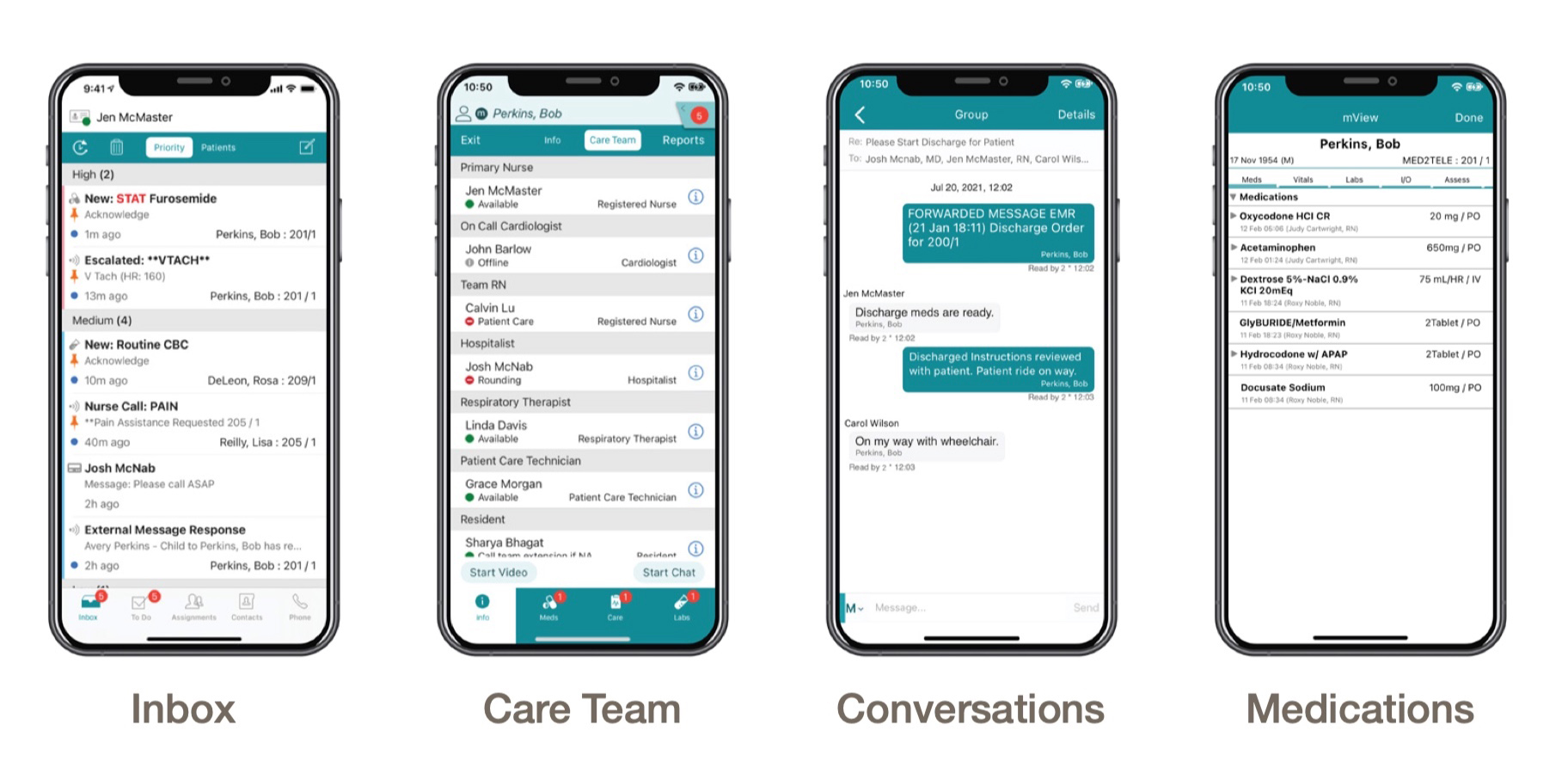

One solution Vocera has created to remedy the issue of communication is a hands-free, wearable communications tool that integrates with smartphone apps to provide patient contextual care to ensure that nurses and physicians get the information they need when they need it — in the right context and on the right platform.

“We put everything in one phone, and you can give the nurses one wearable and they can connect to everybody in the hospital — not just the people they are working with that day,” Collins said of the technology. “There are solutions to these problems, and I do think that it has to be taken seriously because communication is everything; from keeping people safe to causing no harm to patients to facilitating patients through the system. Communication is essential to teamwork and essential to bringing people together with a common goal.”

Vocera Edge, a cloud-based communication solution for smartphones, allows nurses to document electronic health records while receiving filtered, prioritized alarm and task notifications. It also enables physicians to locate and communicate with nurses and other team members supporting their patients.

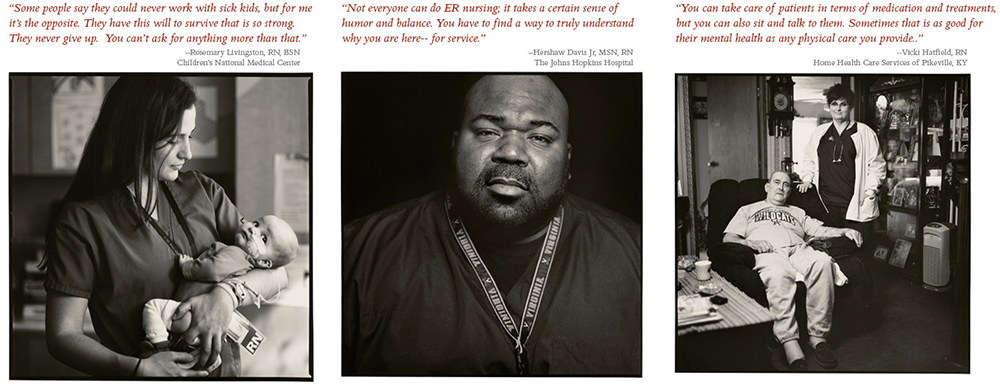

The American Nurse Project

While Collins continues to work with hospitals to improve communications technologies and subsequently improve hospital workplace violence, “Anyone who knows me knows that my heart still resides with bedside nurses that have to do that work every day,” she said. This is made evident in her involvement with The American Nurse, a project aimed to elevate the voice of nurses by capturing their personal stories through photography and film. It includes an award-winning book, three feature-length documentaries, and an ongoing series of interviews.

Collins became involved with The American Nurse when working for Fresenius Kabi, a healthcare company that specializes in medicines and technologies, and the sole financial partner for the project. The book, published in 2012, chronicles the life and work of 75 nurses from across the country.

“We worked together because we were looking for a way to honor nurses and to really bring the voice of the nurse to the forefront,” Collins said. “So we partnered with Carolyn Jones, the photographer and photojournalist who took the pictures and did the interviews. I wrote the afterword in the book and was part of the original documentary. What we really wanted to do was allow nurses in their own voice to tell their story about why they were a nurse and why they do what they do.”

One of the featured profiles is a nurse in Wyoming who is an indigenous Native American. Her grandfather was their tribal medicine man and she speaks about how she has combined both her spiritual upbringing and her scientific education as a nurse to support patients.

Another is of a nurse in Appalachia who drives over mountains and through streams to get to his patients. Coal mining has stripped the hills, causing extreme water runoff that has flooded homes. He keeps waders in his car and carries his equipment in a waterproof bag to access patients in those homes.

“Nurses are committed to the health and well-being. We are there from the beginning to the end, and it’s a very different discipline and practice from the practice of medicine,” Collins concluded. “It’s very much caring for the human body and that spirit in that family. I’m so very proud of my profession.”

Excerpts from The American Nurse; photography and interviews by Carolyn Jones.