This article, originally published in Oct. 2017, was updated on June 20, 2025, to reflect current research, statistics, and events, and to include additional resources.

If you are a victim of sexual assault, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at (800) 656-4673 or chat online at online.rainn.org for help. Additional resources for victims can be found here.

Investigating college sexual assaults is a sensitive process, and to actually prove a sexual assault occurred is an extremely difficult task. Why can sexual assaults be so difficult to prove or disprove? Unfortunately, there are a number of reasons.

The National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC) estimates that two-thirds of sexual assaults aren’t reported to the police (2020). It is the most underreported crime, so just getting the victim to make an official report is the first hurdle, and getting them to follow through in the investigation and adjudication phases can also be a challenge.

One study from the National Center for Campus Public Safety found that 90% of sexual assaults are committed by someone the victim knows, which can lead to confusion on the part of the victim and reluctance to pursue justice. Most victims of sexual assault do not report immediately, especially if it involves a non-stranger assault. This can be due to denial, shock, self-blame, embarrassment, fear of not being believed, or fear of the criminal justice system.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, abuse or assault is:

- Least likely to be reported if the offender is a current intimate partner or former partner (only 25% of these assaults reported to police)

- Less likely to be reported if the offender is an acquaintance or friend (only 18-40% of these assaults reported to police)

- Most likely to be reported if the offender is a stranger (46-66% of these assaults are reported to police)

Additionally, a study from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found more than 50% of college sexual assaults involve alcohol, which can affect recall and make the victim fear being punished or feel shame.

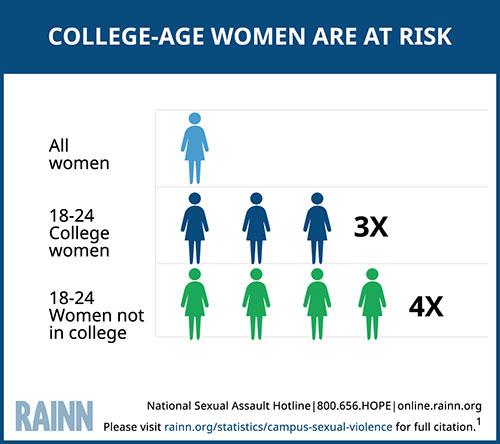

Some additional statistics related specifically to sexual violence on college campuses include:

- 13% of all students experience rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence, or incapacitation (among all graduate and undergraduate students)

- Among graduate and professional students, 9.7% of females and 2.5% of males experience rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence, or incapacitation

- Among undergraduate students, 26.4% of females and 6.8% of males experience rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence, or incapacitation

- 5.8% of students have experienced stalking since entering college

Clery, Title IX, and Sexual Assault

Some college campuses have come under fire — and are paying big — for deliberately threatening or shaming students from reporting sexual assaults for fear it will ruin the school’s reputation. In March 2024, Liberty University was hit with a $14 million fine for violating the Clery Act. A preliminary investigation by the U.S. Department of Education determined the Virginia school violated federal safety laws for years and created a culture that made students fearful of reporting sexual violence.

The penalty is the largest Clery fine in history, dwarfing the Department’s $4.5 million fine in 2019 against Michigan State University over its systemic failure to address claims of sexual abuse committed by former sports doctor Larry Nassar. In the Campus Safety interview below, Kyle Norton, director of regulatory compliance at the Healy+ Group, and Jenn Scott, a regulatory compliance consultant, discuss why Clery Act fines have gotten so big, common Clery Act violations, advice on how college campuses can keep up with Clery Act requirements, and much more. Read the accompanying article here.

Witnesses can also be hard to come by in sexual assault cases generally, and in college specifically because of the prevalence of large, unsupervised parties. Students tend to be at a higher risk at certain times of the year. For instance, more than half of college sexual assaults happen in August, September, October, or November, which is consistent with the first few months of the first semester. For colleges, this period has been widely dubbed “The Red Zone.”

But experienced sexual assault investigators can find ways around all of these hurdles, and justice can be brought even in sexual assault cases without much initial evidence.  It is estimated that one in five women will experience completed or attempted rape during their lifetime. Considerations beyond just the forensic evidence are critical.

It is estimated that one in five women will experience completed or attempted rape during their lifetime. Considerations beyond just the forensic evidence are critical.

New Title IX changes relating to the college sexual assault investigation process might mean different campuses are using different standards, but every college still has the same goal of keeping their students safe and comfortable.

In May 2020, a serious roadblock for sexual assault investigations was implemented when the U.S. Department of Education implemented a new rule for Title IX investigations. The new rule prohibited decision-makers in sexual misconduct investigations from using evidence or statements from someone who did not participate in cross-examination at a live hearing. This received significant criticism from advocates for sexual assault survivors who believe live questioning could re-traumatize victims and prevent victims from coming forward.

In Sept. 2021, the rule was rescinded, allowing decision-makers to consider evidence from involved parties who did not undergo cross-examinations, including police reports, medical reports, Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner documents, and emails and text messages sent leading up to the alleged misconduct.

In April 2024, the U.S. Department of Education released the unofficial version of the final Title IX revisions. The most significant changes include expanded definitions and protections and optional administrative procedures. The new rule has been praised by victim advocate groups and makes “crystal clear that everyone can access schools that are safe, welcoming and that respect their rights,” said Education Secretary Miguel Cardona.

Below we give some best practices for campus police to get to the bottom of any sexual assault report, even with limited or no physical evidence. The information is adapted from The Blueprint for University Police: Responding to Campus Sexual Assault, which focuses on giving law enforcement information on handling rape and sexual assault cases.

Trauma-informed practices, which involve recognizing, understanding, and properly responding to the effects of trauma, are becoming more commonplace during police investigations.

The need for trauma-informed investigations is critical since a 2021 survey from Know Your IX, a survivor- and youth-led advocacy group, found educational disruptions for students who reported their sexual assault to their schools were not from the sexual violence alone, but because of violence exacerbated by schools’ harmful responses to reports of violence.

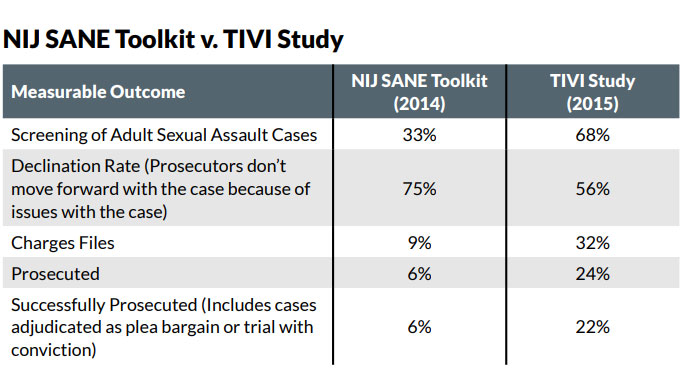

A study conducted by the Salt Lake County Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) determined applying a trauma-informed approach to sexual assault investigations led to more charges being filed and more successful prosecutions.

When a victim feels supported and protected, they are more likely to participate in an investigation and therefore more likely to provide useful information beyond physical evidence.

At the 2023 Campus Safety Conference West in Las Vegas, Al Williams, Assistant Chief of Police for the Ball State University Police Department, shared leading practices for trauma-informed and victim-centered sexual assault investigations. An outline of his presentation can be found here.

Searching for Proof During Sexual Assault Investigations

At first, sexual assault reports can appear to be, “He said, she said” scenarios, where there are little investigators can do to corroborate the accused or accuser’s stories. Unfortunately, experienced sexual assault investigators are familiar with these scenarios.

There can’t always be forensic evidence to work with, but police can still prove sexual assault occurred or didn’t occur with little to no initial evidence, even in cases where there are no witnesses.

Here are nine tips:

- Practice interview techniques such as victim debriefing and adapt an “information gathering” versus interrogation approach to suspect interviews to gather information. Understand physical descriptions (e.g. tattoos), smells and sounds the alleged victim remembers. Here are more facts and myths on sexual assault that police should know.

- Document the specific details of the allegations, all the way down to condom use.

- Gather circumstantial evidence during the investigation, such as a sudden behavior change from the alleged victim. Look for dropped classes, withdrawal from sports or social clubs, and a sudden change in academic performance.

- Try to establish elements of force, threat, or fear if present from either party.

- Look for a serial pattern of behavior from the accused by contacting others who may have been victimized by that person, while being careful not to marginalize the accused.

- Conduct an extensive investigation for corroborating evidence including social media and cell phones.

- Evaluate the need for a search warrant.

- Consider the utility of a pretext phone call to gather evidence from the accused.

- Identify and contact any outcry witnesses.

It is crucial to note that the prevalence of false reporting for sexual assault crimes is extremely low — between 2-10%. Believing victims’ accusations is essential to successful sexual assault investigations.

The above information is adapted from The Blueprint for University Police: Responding to Campus Sexual Assault.

If you are a victim of sexual assault, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at (800) 656-4673 or chat online at online.rainn.org for help. Additional resources for victims can be found here.