This article, originally published July 13, 2023, was updated on Dec. 18, 2023, to reflect current statistics.

Discussions around mental health issues and their prevalence have changed dramatically over the years, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. People are more open and willing to share their mental health struggles yet our country doesn’t have nearly enough providers.

The National Council for Behavioral Health reports that 77% of counties in the U.S. have severe shortages of behavioral health professionals. A Harvard University study recently found just 17% of phone calls placed to get an appointment with a mental health counselor were successful. The U.S. is also 6.4% short of the psychiatrists we need, and the shortage is predicted to nearly double by 2025, reports Recovery.org.

According to Counseling Today, a publication of the American Counseling Association, there are five main reasons for the provider shortage:

- Lack of funding: The government provides a limited amount of funding for mental health services and counseling

- Poor reimbursement rates: Mental health providers are often not adequately reimbursed by insurance companies or government programs

- Low retention: The current number of mental health professionals does not meet the needs of the population

- Increased need for services and limited access to care: The increased demand for mental health services is outpacing the supply of providers

- An aging workforce: Many many health professionals in the U.S. are nearing retirement age

One group significantly impacted by the shortage is students. In a 2021 advisory report, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said a “widespread” mental health care crisis is affecting children, adolescents, and young adults, and it was only accelerated by the pandemic. Murthy pointed to the far-reaching and long-lasting economic and societal consequences that the country could face without age-appropriate and effective interventions.

More recently, in May 2023, Murthy released another advisory warning about the potential effects social media use has on youth mental health. The advisory says recent research shows that adolescents who spend more than three hours per day on social media are twice as likely to experience poor mental health outcomes, such as symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Murthy has called the increase in youth mental health needs “the defining public health crisis of our time,” with suicide as the second leading cause of death for kids ages 10 to 14. Suicide rates increased by 40% among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2019, while emergency department visits for self-harm rose by 88%. The CDC estimates one in five children ages 3-17 have a diagnosable mental, emotional, or behavioral health disorder in a given year. This amounts to 15 million children but only 20% get diagnosed or receive care.

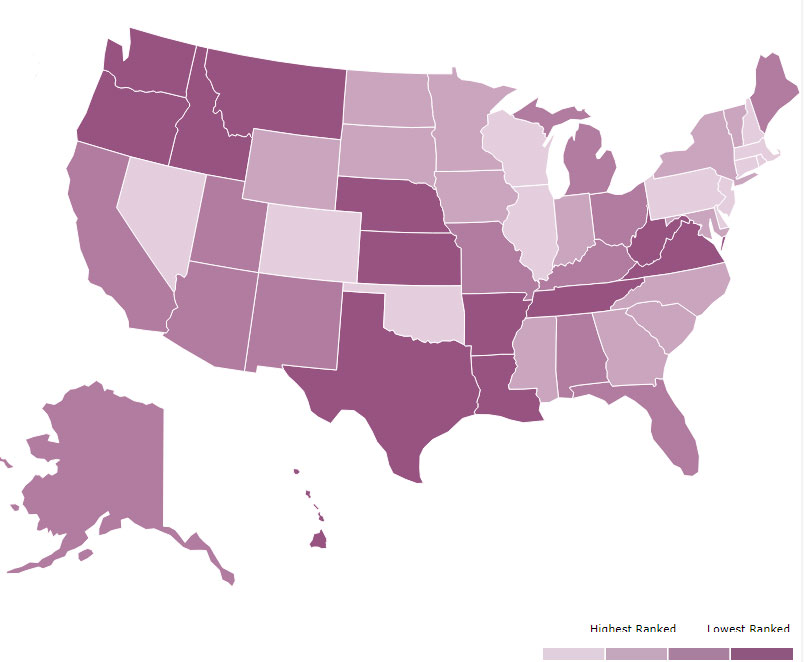

Image 1: This graphic ranks each state by the prevalence of mental illness among youth and rates of access to care. The darker the purple, the lower the ranking. (Graphic source: Mental Health America’s 2023 Youth Data Survey)

A 2023 youth data survey from Mental Health America found 16.39% of youth ages 12-17 reported suffering from at least one major depressive episode in the past year, and 11.5% of youth are experiencing severe major depression. It also found 59.8% of youth with major depression did not receive any mental health treatment. (Image 1 is a heatmap pulled from the study)

Mental Health Care Provider Shortages by State

Before we break down the shortage of school counselors, let’s start with an overview of the shortage of mental health care providers throughout the United States. According to a Dec. 2023 study from Access Across America, in 2021, roughly two-thirds of Americans with a diagnosed mental health condition were unable to access treatment. Additionally, only one-third of insured people who visited an emergency department or hospital during a mental health crisis received follow-up care within a month of being discharged.

The Health Resource & Services Administration (HRSA) regularly measures these deficits using Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) designations. HPSAs are used to identify areas and population groups within the United States that are experiencing a shortage of health professionals, and they can be geographic areas, populations, or facilities.

There are three categories of HPSA designation based on the health discipline that is experiencing a shortage: primary medical, dental, and mental health. The primary factor used to determine an HPSA designation is the number of health professionals relative to the population with consideration of high need, according to health policy research company KFF.

Data from HRSA shows that as of Dec. 17, 2023, 4,652 facilities, 1,284 geographic areas, and 886 population groups have mental health care HPSA designations — up from 4,477, 1,225, and 844 in June 2023 when this article was originally posted.

The data also shows 169 million Americans live in these mental health care HPSA designations — around 49% of the population — with over 8,504 more professionals needed to ensure an adequate supply. In June 2023, those numbers were 163 million and 8,250, respectively.

KFF gathered state-by-state mental health care HPSA data through Nov. 1, 2023. One of the data measurements, the ‘Percent of Need Met,’ is computed by dividing the number of psychiatrists available to serve the population of the area, populations, or facility by the number of psychiatrists that would be necessary to eliminate the mental health HPSA. Here’s that breakdown from highest to lowest Percent of Need Met:

- Rhode Island: 61.9%

- New Hampshire: 57.8%

- Utah: 54.3%

- New York: 51.1%

- Nebraska: 47.9%

- Georgia: 43.2%

- Virginia: 41.6%

- Wyoming: 41.2%

- Massachusetts: 41.1%

- Mississippi: 39.5%

- District of Columbia: 39.3%

- Wisconsin: 38.4%

- Pennsylvania: 37.8%

- Michigan: 36.1%

- Colorado: 34.3%

- Arkansas: 33.7%

- Oklahoma: 33.6%

- South Dakota: 33.5%

- Indiana: 31.1%

- Ohio: 30.9%

- Texas: 30.9%

- Iowa: 30.6%

- Nevada: 28.6%

- Oregon: 27.8%

- Minnesota: 27.3%

- Montana: 27.3%

- Idaho: 26.4%

- South Carolina: 26.4%

- Louisiana: 26.2%

- Alabama: 25.4%

- Kansas: 25.4%

- Kentucky: 24.2%

- California: 24.0%

- Maryland: 22.5%

- North Dakota: 22.3%

- Illinois: 22.0%

- Florida: 21.8%

- Maine: 19.7%

- Connecticut: 19.0%

- New Jersey: 17.9%

- Washington: 16.9%

- Tennessee: 16.3%

- New Mexico: 14.4%

- Hawaii: 14.1%

- West Virginia: 13.0%

- Missouri: 12.4%

- North Carolina: 12.1%

- Alaska: 11.9%

- Delaware: 11.6%

- Arizona: 9.1%

- Vermont: Data not provided

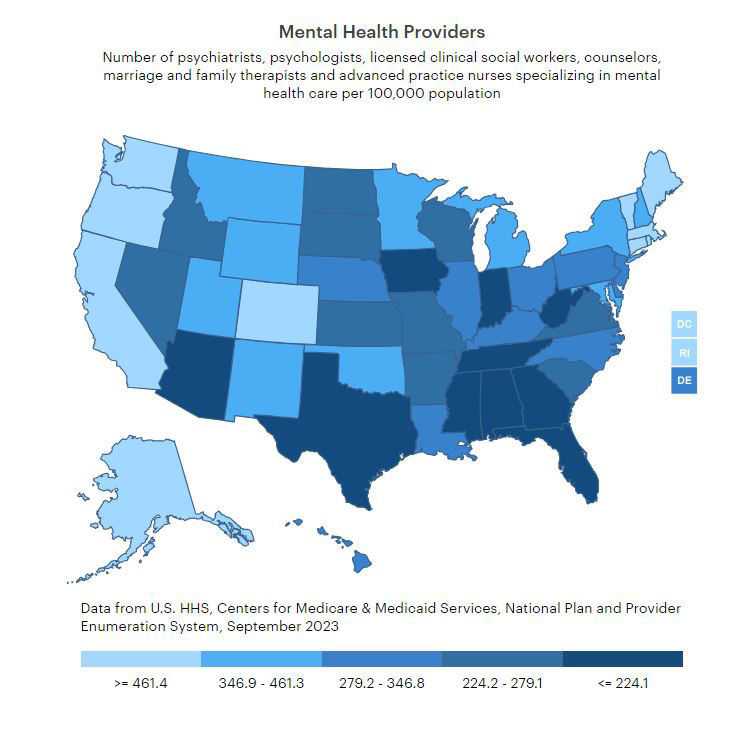

Image 2: This graph shows the number of psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed clinical social workers, counselors, marriage and family therapists, and advanced practice nurses specializing in mental health care per 100,000 population. (Graphic source: www.americashealthrankings.org)

It is important to note that the above data from KFF and HRSA only includes psychologists; it does not address the shortage of other mental health providers. A Sept. 2022 study from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services looked at the number of all mental health providers in the U.S., including psychologists, psychiatrists, licensed clinical social workers, counselors, marriage and family therapists and advanced practice nurses specializing in mental health care.

HHS’ study, last updated in Sept. 2023, estimates there are 324.9 U.S. mental health providers per 100,000 people — up from 305 last year. Massachusetts has the highest ratio of mental health providers at 758.7 to every 100,000 people while Alabama has the lowest at 140 — although that’s up from 128.8. A state-by-state breakdown can be found here. (Image 2 is a heatmap pulled from the study)

School Counselor Shortages by State

Due in part to a lack of mental health professionals, a recent survey on school safety found 60% of K-12 school leaders cited mental health issues as the greatest school safety obstacle they are currently encountering, and more than 50% feel ill-equipped to assist students with those challenges.

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends at least one counselor for every 250 students. However, only two states met that criteria as of Dec. 2022: Vermont (186:1) and New Hampshire (208:1). The national average is 444 students per counselor. The state with the highest ratio of students to counselors is Arizona at 716:1.

It is important to note the difference between school counselors and school psychologists. School counselors are a resource for the entire student population and focus on individual or group sessions to build skills to overcome social and behavioral challenges and improve academic performance, says Charlie Health. School psychologists conduct mental health evaluations, diagnose mental health issues, and write individual education plans.

There is also a significant shortage of school psychologists. According to the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), the recommended ratio is one school psychologist for every 500 students. Data from NASP shows that as of Jan. 10, 2023, the national average is one psychologist to every 1,127 students — over 100% more than the recommended ratio.

While the data sets used in this article are not all direct comparisons, a lack of overall mental health support in schools means more students will turn into adults who do not have the proper knowledge or understanding of how to address their mental health needs or challenges, and the current state of available mental health professionals outside of a school setting will only compound their struggles. A recent survey by Inside Higher Ed also found about 65% of college presidents indicate they plan to increase their institution’s capacity to meet the mental health needs of students, staff, and faculty members — a smart move since another recent study from TimelyCare found nearly 60% of college students received mental health care during their K-12 years.

Using employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and school counselor-to-student ratio data from the ASCA and the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) through Dec. 2022, Charlie Health, a provider of virtual intensive outpatient (IOP) treatment programs for youth and their families navigating mental health challenges, ranked states from best to worst in counselor-to-student ratios for elementary through secondary schools.

Here’s an overview of all 50 states, plus D.C., from best to worst school counselor-to-student ratio:

- Vermont: 443 counselors to 82,401 students (186:1)

- New Hampshire: 813 counselors to 169,027 students (208:1)

- Hawaii: 659 counselors to 176,441 students (268:1)

- Colorado: 3,177 counselors to 883,199 students (278:1)

- Montana: 503 counselors to 146,252 students (291:1)

- Maine (tie): 581 counselors to 172,455 students (297:1)

- North Dakota (tie): 387 counselors to 114,955 students (297:1)

- Tennessee: 2,542 counselors to 985,207 students (301:1)

- Wyoming: 298 counselors to 92,772 students (311:1)

- Virginia: 3,940 counselors to 1,251,639 students (318:1)

- Missouri (tie): 2,716 counselors to 882,477 students (325:1)

- West Virginia (tie): 782 counselors to 253,930 students (325:1)

- North Carolina: 4,638 counselors to 1,513,677 students (326:1)

- Maryland: 2,662 counselors to 882,527 students (332:1)

- South Carolina: 2,282 counselors to 766,819 students (336:1)

- New Jersey: 4,072 counselors to 1,373,960 students (337:1)

- Connecticut: 1,458 counselors to 509,058 students (349:1)

- New York: 7,446 counselors to 2,606,748 students (350:1)

- Pennsylvania: 4,835 counselors to 1,704,396 students (353:1)

- Arkansas: 1,346 counselors to 486,305 students (361:1)

- South Dakota: 385 counselors to 139,566 students (363:1)

- Massachusetts: 2,534 counselors to 921,712 students (364:1)

- Kentucky: 1,798 counselors to 658,809 students (366:1)

- Nebraska: 880 counselors to 324,697 students (369:1)

- Iowa: 1,369 counselors to 506,656 students (370:1)

- Oregon: 1,499 counselors to 560,917 students (374:1)

- Delaware: 362 counselors to 138,092 students (381:1)

- Wisconsin: 2,143 counselors to 830,066 students (387:1)

- Texas: 13,696 counselors to 5,372,806 students (392:1)

- Kansas: 1,217 counselors to 481,750 students (396:1)

- Oklahoma (tie): 1,744 counselors to 694,113 students (398:1)

- Mississippi (tie): 1,111 counselors to 442,627 students (398:1)

- Ohio: 4,082 counselors to 1,645,412 students (403:1)

- Rhode Island: 336 counselors to 139,184 students (414:1)

- Alabama: 1,769 counselors to 734,559 students (415:1)

- Georgia (tie): 4,130 counselors to 1,730,015 students (419:1)

- Alaska (tie): 310 counselors to 129,872 students (419:1)

- Florida: 6,428 counselors to 2,791,707 students (434:1)

- Washington: 2,465 counselors to 1,087,354 students (441:1)

- New Mexico: 716 counselors to 316,840 students (443:1)

- Louisiana (tie): 1,557 counselors to 693,150 students (445:1)

- Nevada (tie): 1,085 counselors to 482,348 students (445:1)

- District of Columbia: 195 counselors to 89,883 students (460:1)

- Indiana: 2,176 counselors to 1,033,964 students (475:1)

- Idaho: 623 counselors to 307,581 students (493:1)

- Utah: 1,251 counselors to 680,659 students (544:1)

- California: 10,602 counselors to 6,064,504 students (572:1)

- Minnesota: 1,473 counselors to 872,083 students (592:1)

- Michigan: 2,246 counselors to 1,434,137 students (638:1)

- Illinois: 2,838 counselors to 1,886,137 students (665:1)

- Arizona: 1,552 counselors to 1,111,500 students (716:1)

Overall, school counselors are there to serve all students, regardless of their mental health status. They are often the ones who spot a student that may be struggling with their mental health, and can offer them support and point them toward available resources before symptoms escalate.

The shortage is school counselors is only compounded by the shortage of teachers. Those statistics and a breakdown by state can be viewed here.

What’s Being Done to Improve Student Mental Health Support?

According to a 2022 study from the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), 48% of all schools report they do not have enough funding to provide adequate mental health services with more than two-thirds reporting an increase in the percentage of students seeking mental health services from school since the state of the pandemic. To help pre-K through 12th-grade students recover from time lost in schools during the pandemic, the Biden Administration established the $122 billion American Rescue Plan Act’s (ARPA) Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) in 2021.

The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act of 2022 also committed more than $1 billion in the next five years to support schools in addressing youth behavioral health needs. The law directs HHS and the U.S. Department of Education to create a technical assistance center that will help states and schools better use Medicaid dollars for school-based services. In July 2022, the department and HHS issued a joint letter to governors encouraging partnerships at state and local levels and outlining resources to support youth with behavioral health needs.

In Oct. 2022, the Education Department earmarked $280 million for two grant programs to increase access to mental health services for students and young people. The first program, School-Based Mental Health Services (SBMH), provides funding to schools to increase the number of credentialed school-based mental health professionals, according to a press release. The second program, the Mental Health Service Professional Demonstration (MHSP), supports districts in hiring additional school-based mental health service providers in high-need districts by boosting the mental health profession pipeline. This includes investing in partnerships between school districts and institutions of higher education to prepare qualified school-based mental health service providers for employment in schools.

In Feb. 2023, the Education Department announced it awarded more than $188 million to 170 grantees in over 30 states. The department estimates the grant money will help the communities hire approximately 5,400 school-based mental health professionals and train an additional 5,500 more.

To help schools access these funds, Effective School Solutions (ESS), which provides clinical programs, professional learning, and consulting services to help districts introduce mental health best practices, released a national seven-part framework guide.

Texas Schools Push for Dedicated Mental Health Funding

While ESSER funding has helped schools increase their mental health resources, schools, districts, and states have voiced concerns about what happens when that funding runs out. ESSER II money is set to expire in Sept. 2023 and ESSER III money is set to expire in Sept. 2024. Additional funding will be needed to continue employing the new mental health professionals and other resources and programs implemented to support student mental health needs.

Texas schools, for instance, received $19.2 billion during the pandemic through several iterations of the ESSER fund, according to data from the Texas Education Agency (TEA). Of the 714 school districts that participated in a statewide survey, over 73% said they used the funds for mental health initiatives.

Cory Green, the associate commissioner for the TEA’s Department of Grant Compliance and Administration, told the Austin American-Statesman that there “will come a point in time when district budgets are going to go back down to what their normal spending level is.”

“It’s hard for us to predict great outcomes when this fiscal cliff is coming at the end when the ESSER dollars dry up,” said Adrian Kohler, policy director at Texans Care for Children. “Overall, the expiration of ESSER funds will absolutely put at risk many of the innovations for mental health.”

Texas is one of the worst states for psychologist-to-student and social worker-to-student ratios. Texas schools have one psychologist for every 2,600 students — more than five times the recommended ratio. The statistics are even more staggering for social workers. The School Social Work Association (SSWA) recommends one social worker for every 250 students. In Texas, it’s one for every 5,200 students — more than 20 times the recommended ratio.

Texas school officials and mental health advocates also fear several school safety bills passed since the 2018 Santa Fe High School shooting that claimed the lives of 10 people will be used mostly for school security instead of maintaining student support services established during with pandemic using ESSER funds.

“We think it’s critically important that our campuses are safe, but we also want to make certain that legislation moves forward that has mental health in mind so we don’t miss the resources needed to continue mental health initiatives at a school level,” said Seth Winick, director of the Texas Coalition for Healthy Minds.

Texas school officials are urging lawmakers to create a dedicated funding source for mental health needs that isn’t tied to school safety spending, according to The Texas Tribune. In May, 36 Texas health and wellness organizations wrote to the Texas Legislature, urging the creation and funding of a separate “student mental health allotment” in the remaining weeks of the session.

“The Legislature is taking important, positive steps this session to address children’s mental health — but there is a major gap in the bills that are moving,” reads the letter. “The Legislature’s mental health plan needs to reach a much larger number of children and include support for prevention and other strategies that reach children before a crisis.”

Experts: Universal Mental Health Screenings Key to Combatting Youth Anxiety, Depression

To address the growing youth mental health crisis, public health experts agree universal mental health screenings are critical and must start at a young age.

In Oct. 2022, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that primary care doctors screen all children ages 8-18 for anxiety, regardless of whether or not they are showing symptoms, and that screening and follow-up care can reduce symptoms. From 2016 to 2019, around 5.7 million children were diagnosed with anxiety and depression, according to CDC data. The guidance also confirmed previous recommendations that children ages 12-18 should be screened for depression.

Child psychologist Irina Gorelik told CNBC that when anxiety and depression symptoms are noticed by school personnel, it has usually already affected a child’s academic performance. A primary care doctor might be better equipped to recognize signs and symptoms that “maybe be harder to observe earlier on,” she added.

Gorelik also said universal screenings may decrease the embarrassment children might feel after a diagnosis and that screening all kids “can help to minimize stigma around mental health issues and help jumpstart conversations around support.”

Schools are also encouraged to adopt universal mental health screenings to identify students in need of support. According to a poll commissioned by ESS, only 40% of administrators say their school has adopted broad-based mental health screening initiatives.

In May, ESS released a six-point leading practices guide for districts, states, and federal policymakers to reinvent mental health in schools over the next five years. Each step, one of which dives deep into the importance of universal mental health screenings and where to begin, has recommendations for both districts and state and federal groups. The full guide with more details and recommendations can be read here.

A study published in the National Institute of Health’s National Library of Medicine outlines the process of universal behavioral and emotional health screenings in schools, including challenges, considerations, misconceptions, and feasibility.