Cardiac arrest doesn’t just happen to adults who are middle aged or elderly. America was reminded of this fact on January 2, 2023, when 24-year-old Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field from a heart attack he experienced during his team’s game against the Cincinnati Bengals. Fortunately, Hamlin was resuscitated with CPR and an automated external defibrillator (AED).

Hamlin’s health scare — which millions witnessed because the game was nationally televised – made a lot more Americans aware of the risk of cardiac arrest in young people and how CPR and AEDs can save lives.

According to the American Heart Association, sudden cardiac arrest affects between 7,000 and 23,000 children under the age of 18 every year. (The actual number, however, is probably higher.) Additionally, between 2004 and 2008, the rate of sudden cardiac arrests among NCAA athletes was 2.3 cases per year.

Hamlin’s medical emergency prompted University of Vermont (UVM) administrators to take notice of the risk of cardiac arrest on campus, whether the victim is a young student or perhaps a staff member or visitor who is older. The day after the Hamlin incident, UVM Provost and Senior Vice President’s Chief of Staff Kerry Castano spoke with Director of Emergency Management John Marcus about what happened at the Bills-Bengals football game and the status of the school’s AEDs.

Cat ECare Enables Quick, Life-Saving Response to Cardiac Arrest and Other Medical Emergencies

Prior to Hamlin’s nationally televised cardiac arrest, the school had some AEDs distributed around campus. However, the equipment really wasn’t managed in an organized way. It wasn’t standardized, people weren’t trained how to use the AEDs, and maintenance was a challenge.

Fortunately, Marcus and his team of student interns had already been developing a solution: the Cat ECare program. UVM Provost and Senior Vice President Patty Prelock responded to Marcus’ proposed program by immediately committing the funding to provide AEDs in seven classroom buildings.

Related Article: How a Brown County Kansas School Safety Initiative Made Its Entire Community Safer

Cat ECare emergency stations, which are distributed around campus, include AEDs. However, Marcus and his team made the stations even more useful by adding bleeding control kits and Narcan.

Additionally, embedded within the program are ongoing training opportunities for UVM students, faculty, and staff. Training covers CPR, how to use AEDs, bleeding control, and how to use Narcan.

UVM now has 100 Cat ECare emergency stations located all around campus. Not only does this equipment prepare the school to save a life should someone experience a heart attack or some other medical emergency, it’s a great opportunity for UVM students to get involved in service to the community, enriching their college experience.

The Cat ECare program was just one reason why Marcus was named a finalist in this year’s Director of the Year program.

In my interview with Marcus, he describes:

- The origins of Cat ECare and what Cat ECare means: 1:13

- How he involved student interns and other campus partners to help develop the program: 3:04

- How he and his team expanded the program: 3:52

- Getting support and funding for Cat ECare: 7:17

- Results of the program: 16:01

- Maintaining equipment, supplies and support for Cat ECare: 18:52

The transcript of the interview is below the following video:

Hattersley: What is the Cat ECare program?

Marcus:

Our mascot is the Catamount, so a lot of our programs and different things that we do have a cat name to them. So CAT eCare is short for Catamount Emergency Care, and that involves the placement of stations around campus that contain automated external defibrillators or AEDs, stop the bleed kits for severe bleeding and Narcan or Naloxone for opioid overdose reversal. And along with that, there’s a training component as well that I’d like to talk about.

Hattersley:

Right? I’m sure that’s for CPR, first aid, things like that. Bleeding control?

Marcus:

Yes. Yes. I can tell you a little bit about how the program came into being. We had a smattering of AEDs around campus for a few years. It was something that departments just kind of bought on their own, and there was no rhyme or reason to where they were, what brand they were, who was maintaining them, whether anyone knew they were there, whether anyone was trained in them. And I have a background in emergency medical services and the fire service. And I looked at this and it was a risk management problem and it was not a really good public safety solution. So I started thinking about what we could do to maybe make things better, increase what we had and get some training involved as well. So I reached out to a student intern that I was working with and I said, I have a new project.

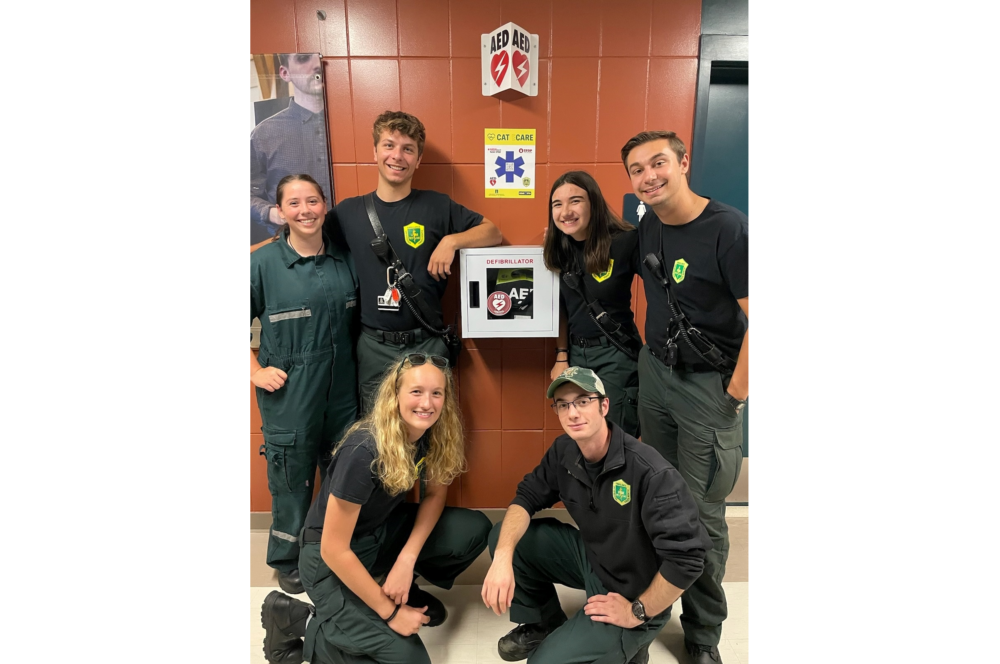

Let’s talk about AEDs on campus. So we did a lot of brainstorming and the semester ended, I got new interns and we decided to bring in some campus partners. We have a college of medicine here, we have a school of nursing and health sciences, and we have a completely student run advanced life support rescue squad on campus that operates two ambulances, 24-7, holidays, summers, all that. And they serve the surrounding community as well. So we got representatives from all those groups and we sat down and started figuring out what we could do to try to increase the number of AEDs on campus and provide a training program.

Hattersley:

Did you notice any particular trend besides the AEDs? Did the program just sort of expand from there, “We got some AEDs now, oh wait, people need to be trained on CPR and oh, maybe they need to know about bleeding control.” Is that kind of how it happened?

Marcus:

Well, this is the great thing about working with students and I mean really engaging them, not just sitting at a table and waiting for them to come talk to you or handing them a brochure, giving them a social media account to follow or something. Really actively involving them and giving them agency and a stake in things. So I was thinking AEDs and along with AEDs, I think high quality CPR, because AEDs are designed to be used by the public, by lay people. They walk you through how to use them. But research has shown that with high quality CPR and an AED, somebody’s survival from a sudden cardiac arrest that the rate dramatically increases if you add that CPR and training on how to use an AED and the comfort level as well of somebody actually taking that off the wall and attending to the person in distress.

So I was really in tune to that training issue in the AEDs and CPR. And we had been independently looking at active threat response and things like that. And we had talked about Stop the bleed kits and how we could augment the emergency medical response to an active threat.

Related Article: How Bystanders Can Use Med Tac Training to Save Lives

One of the students said, “Why don’t you put the stop the bleed kits in the AED cabinets?”

Why didn’t I think of that? I was thinking of budgets and hours and other things and not putting stop the bleed kits in the AED kits. So we talked about that and we’re like, there’s a training program for that. We can train people in that.

And then this group of, we have a faculty member from the College of Nursing and Health Sciences, myself and my interns and a representative from the Student Rescue Squad. We meet monthly and one of the employees, either me or the faculty member takes turn buying coffee for the group. The weekly meeting is in a coffee shop on campus and we buy the students coffee. And at one of the subsequent meetings, one of the students said, Narcan isn’t really widely available on campus. And it’s an issue everywhere, I’m sure.

Hattersley:

Absolutely.

Marcus:

Yes. The surrounding area here, campus, nobody’s immune from it: students, professors, staff. It’s a huge thing. And accessibility is key. And there are places where you can get [Narcan] on campus, but you have to know where to go. It’s only during business hours, things like that. And somebody said, could we make that more available? And if there’s kind of a place people are looking for emergency equipment, why don’t we put it in there? So that was added again at the suggestion of a student.

Hattersley:

That’s great. Now let’s back up a little bit here. How did you get support for this program in the first place, and how did you get the funding for it? That’s always the multimillion dollar question, right?

Marcus:

That is the multimillion dollar question. So the AEDs, the first thing we did is we talked to our people here. We have a department that maintains medical equipment because we have a medical school and we’re affiliated with a teaching hospital. We have a department that does nothing but maintain medical equipment. So they know a lot about AEDs and they’re able to give us a quantity discount.

They purchase AEDs along with the state health department and some of the hospitals in the state so we can get really good pricing on them. So we said, what’s the model? We want one model. Right now we still have some older models and there’s supply chain issues and getting the pads and the batteries and everything. Some are two year pad pads, some are four year pads, some of the batteries are five years, some they’re proprietary batteries, some they’re Duracell camera batteries.

So we ask them to standardize the AEDs for us and then give us a rock bottom price. We asked the departments or the occupants of a building to buy the AED, and it’s about $1800 to $1,900 right now for the AED, including the cabinet, the sign. And then I buy bleeding control supplies in bulk from a medical supply company. I buy plastic bags from an office supply company, and I make up labels on my office printer. And my student rescue volunteers sit down with a hundred plastic bags, 200 tourniquets, 200 dressings trauma sheers, nitro gloves, and they assemble the kits for me and put our custom branded sticker on it. We can produce those at about half the price of a commercially available stop the bleed kit. So my budget furnishes those and the Narcan we’re able to get that for free through a state program. So essentially if a department pays for the AED and a cabinet, I pay for the installation, I pay for the maintenance, I provide the bleeding control kit, and I provide the Narcan. So it’s kind of a synergy kind of thing where you buy a little and you get a lot.

Hattersley:

So what was your pitch to the top administrators and to the department heads about this program? I mean, $1800 bucks. When you think about saving a life, that doesn’t seem like much money, but when you’re laying out 1800 bucks per department, that can be quite an expenditure. What’s your pitch to get them to buy into this thing?

Marcus:

So there’s a saying, and I always mess up sayings, which is why the students love me, but luck is where opportunity meets preparation. And in January of 2023, there was a nationally televised football game where a player, DeMar Hamlin of the Buffalo Bills, a young perfectly healthy athlete, had a sudden cardiac arrest in front of millions of people on TV and was resuscitated because they had people trained in CPR and had an AED on site and came back and today is playing in the NFL again.

We were on break. That was early January, and we were doing a lot of the training and tabletop exercises and things that we tried to squeeze in when the students aren’t there. And the provost came out to me and said, what’d you think about that DeMar Hamlin thing? And I said, yeah, that was really amazing.

Really everything worked out. And she said, do we have those machines here? And I said, funny that you mention that, because I’ve been working with some students on a program and we’re trying to develop this. And she said, give me a quote for, and she named seven buildings and she said, I want to fully outfit these seven buildings. And after that, it just became kind of a momentum thing. It’s like sometimes you just have to get out of the way when something starts. And we made up the program, we branded it with a cat name, we made up a logo, and we went out there and started promoting it at the different health fairs and safety fairs and orientations and things like that. And it was a thing.

Hattersley:

So now how did you broach the topic with students? How did you get them involved? I mean, are you regularly involved with students anyway? And was this just sort of an add-on type of a thing or did you have to pretty much launch this thing from the get-go?

Marcus:

I’m the advisor to the student run ambulance service. So I have contact with them all the time. We work very closely together. They’ve been in existence for 52 years, continuously, a very well respected organization in the area, and they’re completely run by students, nine elected student officers for everything from director training equipment, vehicle personnel. They understand the importance of early intervention in everything: cardiac arrest, opioid overdose, severe bleeding. So they were with me right from the start. Also, four years ago, public health became very intermingled with emergency management. Emergency management used to be about earthquakes and floods and fires and hurricanes and things like that. And all of a sudden public health became a big part of emergency management and emergency preparation. And we have a really good public health sciences undergraduate program here.

I had been getting interns from that program. And these are students who are in public health, but they’re interested in emergency preparation, emergency management, and they were kind of the ambassadors for this. They went out and talked to people. Coming up, we have I think 60 students who belong to student clubs, like the rugby club and the soccer club, and we have 60 students who are about to go through our training. Our students have gone out and talked to people. We have a ski club, and they said, “Hey, you really should have this training, being an outdoor club and all that kind of stuff.

So between my public health sciences interns and my rescue student volunteers, they’ve really done all the heavy lifting for me. I just sit back and smile and buy them coffee and they go out and preach.

Hattersley:

So I guess the moral of the story is if you’ve got a teaching hospital or a nursing school, they’re a prime audience for this, correct?

Marcus:

Yeah, absolutely. But I wouldn’t limit it to that. We have a lot of students who come here who have been lifeguards or done work, worked in some kind of park or childcare or something where they’ve had this kind of training. A lot of them would be excited to be able to continue it and maybe work in a program like this. So it doesn’t necessarily have to be an undergraduate program or students in an organized rescue squad or anything like that. It’s just finding like-minded people who want to get involved in a project.

Hattersley:

So what have been the results of this program? It is been going on for about a year now. Is that right?

Marcus:

This is really our second year of having a full class schedule. The training we have, it’s conducted entirely by students. So they take American Heart Association, basic Life Support instructor certification, so they’re able to deliver the training and certify the participants.

They’re also stop the lead instructors. With Narcan, there’s no formal training or certification for, but it’s just an introduction and an overview. So I have a core of student instructors, which the nature of college is that you have a certain number of students graduating or leaving every year, and you have to keep training new people, but you get fresh perspectives and fresh ideas and diversity into the program by doing that.

So they teach the classes, and we teach a regular class on Monday evening and a regular class on Friday afternoon all semester long. We have a registration system that the university provides at no cost to the program. So people can just click a link on our website and go online and see all the classes and pick one and register for it.

And then we do a lot of special groups, this being the week before the students come back for the fall semester, we’re training a lot of student employees. We’re training a lot of groups. There’s an outdoor trip that goes out the week before classes start, and all their leaders, 40 of their leaders have just been through the training. So we set up special training for them. So it’s really, it’s been talked about and we’ve been designing logos and making up names and things for about three years now. But this is really our second year of offering a full slate of classes.

We now have 99, we call them Cat eCare stations, but the AED, the Stop the Bleed Kit and the Narcan, we are going to install the 100th and we’re going to have a little ceremony with the provost and the dean of the College of Medicine and the Dean of the College of Nursing and Health Sciences and some of the students who were involved. So I haven’t got a response from them yet. I just invited them today when I realized we were at 99, I was like, oh, we’ll put up the hundredth and we’ll have a little party.

Hattersley:

Absolutely. Since the program’s been going on for a little bit, I know that sometimes when programs start, there’s a lot of energy and excitement about it, and then things kind of trail off and people stop paying attention to it. How do you maintain that energy and that excitement?

Marcus:

Again, it comes back to the students. I hate to beat the same drum, but we have new students every semester. We ended up being so successful that I actually hired a student employee over the summer. Pretty much every semester we get brand new students, we get new interns from the public health sciences program, we get a new representative from the rescue squad. The faculty member who started this with us was going to retire last year, and he actually postponed his retirement, went to his dean and said, I want to work part-time and work on this program and teach one or two classes. He said it put a bounce back into his step. It gave him a reason to come to work every day.

And it’s just, I think you get new young people coming into the program, coming into the meetings, and they’ve got ideas and they’ve got energy and they’re seeing something. We give them a look behind the scenes as well. I mean, when something doesn’t go well, I’m very honest with them and not at all censored with my language or my feelings about if something doesn’t go well. But things like the registration system, and we’re moving to a case management system. When people email us about something — they didn’t get their certification card or something — we had shared an email inbox and there’s always a lot of confusion about did somebody answer that email or whatever. So we’re going to a case management system now and we’re implementing that this fall, and the student interns will be involved in that implementation.

The earlier students got to see how the registration system was set up and the information that we gathered from registrants and the things we tell them, wear comfortable shoes and do this and that, and this is what the class will be. And now this case management system, they’ll be involved with the developer talking about what reports do we want to be able to generate and what tracking do we want to do, and who’s going to have access and what email templates do we want to use and what knowledge base articles do we want? So they get a little bit of something new every year, and we’re constantly trying to figure out what we can do to keep it fresh and keep people engaged.

Hattersley:

Speaking of keeping it fresh, I know that AEDs don’t last forever. Batteries wear out, the pads wear out, the Narcan probably has an expiration date. How do you keep track of all those supply chain issues?

Marcus:

That was one of the issues initially that led us to get more involved in this program. And the department that I mentioned before, technical services partnership that does all the equipment. We contract with them to inspect every unit once a month. They inspect the AED, the pads, the Narcan expiration date, make sure everything’s in the bleeding control kit and all that. And they have a database so they know when every piece of equipment is going to expire and where it is. And they give me spreadsheets.

That is the one thing that my department does pay a good bit of money for, but it’s well worth it. And there are two technicians who are involved in the program and they’re really invested in it. Sometimes they stop by at our meetings and talk to the students, and we have them explain to the students what they look for when they inspect an AED and things like that. They’ll come to our hundredth AED celebration. And for them, it’s not just checking a piece of equipment. They’re highly invested in it. But it is a contract that we pay for to have everything inspected and tracked.

Hattersley:

And have there been any medical emergencies where these kits have been deployed and used and possibly saved a life?

Marcus:

There have not yet. We do have a history of a couple of saves on this campus. Before the program started, there was one at a basketball game where a coach had a sudden cardiac arrest and there was a faculty member who had a sudden cardiac arrest, and there happened to be EMTs standing by at both times that that happened. So it has happened in the past, but we have not had anything yet.

Hattersley:

Well, and truth be told, it doesn’t just happen to older adults, it happens to young adults, it happens to kids, or maybe they slice their hand or something and they need a bleeding control kit or the opioid addiction that’s been going around for so long. I mean, there’s so many uses for these types of systems. I really love them. Any sage advice for other campuses wanting to set up a similar program like Cat eCare?

Marcus:

I do want to say one more thing about it as far as what we’ve done out of this program and that we haven’t necessarily, they haven’t used the equipment to save anyone yet. But I get emails from former students and they say that the time we spent working on Cat eCare was absolutely the best time they had in four years of college. So there’s the program and there’s the saving lives and stuff, which is not to be discounted, but in tandem with that, we are giving these students this experience that they’re talking about. Pur student instructors are leaving here with the ability to teach basic life support and certify people. And if I’m a prospective employer and I’m looking at a student’s resume and they’re like, “Hey, they can teach all the other employees how to do CPR and use an A ED and stop the bleed on Narcan.”

Hattersley:

Well, and you never know when they’re going to actually go out into their own communities or in their lives, and they may be standing in line at McDonald’s and someone has a heart attack and they can administer CPR.

Marcus:

That’s a huge thing. And we’re a land grant university, and part of our mission is to serve the state and have a lot of our students come from very rural areas where EMS may be 20 minutes away. Having these people go back to their towns of residence or working in places where they’re trained to do these things, it’s fantastic.

But back to your question that I derailed about my sage advice, I think that I don’t like committees and groups for doing things. I find a lot of committees and groups can be unproductive and very slow moving and difficult to get things done. But I think in a case where you’re kind of starting something brand new, it is really great to have different people at the table if you are a staff member, if you’re a police chief or a public safety director or something like that. Involve faculty, students, student government, things like that. And student clubs, volunteer organizations get these people at the table.

They’ve got a tremendous wealth of experience and knowledge and stuff that they bring to the table. So I think if you want to start something new or create something or drastically rebuild or improve something, don’t try to do it by yourself and don’t try to do it in a silo with other public safety people or emergency management people, or law enforcement people.

Get people around the table, buy them coffee and don’t just hand them a sticker and say, put this on your water bottle, but say, “Hey, we want to do this. What do you think we should do? What do we need? How do we do this?” That’s the engagement of the whole community.

Hattersley:

Bribery with coffee will do wonders. John, anything else you want to add before we close?

Marcus:

I don’t think so. I’ve enjoyed talking to you, and I’m really proud of this program. I know that AEDs are becoming a lot more common in public places. You see them everywhere and college campuses as well. And this isn’t really something groundbreaking and earth shattering that we did something that nobody’s ever done before. But I’m just very proud of the way that we did this and that it’s continuing to sustain itself and grow our students and involve them in health and safety here on our campus.

Hattersley:

John, thank you so much. And thank you everybody for watching.

Marcus:

Thank you, Robin.