The views expressed by guest bloggers and contributors are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, Campus Safety.

In a recent article1, I identified four fallacies, embraced by most law enforcement agencies and schools, that are likely to undermine the effectiveness of their active incident plans.

First, most agencies and schools focus almost exclusively on the response phase, i.e., what to do upon the outbreak of gunfire. Less attention is paid to the three other phases of a crisis: prevention, which precedes response, and mitigation and recovery that follow it. Certainly, officials recognize the importance of preventing a shooter but magnetometers, gunshot detection, and similar technologies will not prevent a determined individual from accessing a school or public venue and engaging in mass killing before responders can arrive to neutralize the threat. Furthermore, “see something, say something” compliance is spotty at best; people see many concerning behaviors but say nothing because they don’t want to turn in a friend, don’t want to get involved, fear retaliation, are not certain they are observing a crime, etc.

The second fallacy complements the first. Schools generally rely on law enforcement responders to deal with the threat but fail to recognize the critical roles of other stakeholders. Other entities, such as school administrators, parking, facilities, grounds, IT, the public information office, student life, and others have critical roles to play, often in several, if not all, phases of the active incident.

Third is the mistaken belief that all stakeholders have identical goals. Universal goals such as preventing an active incident, minimizing loss of life, and limiting property damage are too broad to be useful for planning. For instance, in the prevention phase, police may want to conduct omnipresent monitoring, the ubiquitous staging of tracking and surveillance technologies, and intrusive investigations of people’s movements but faculty, staff, and students are likely to object to working and studying in such an Orwellian environment. In the recovery phase, police and facilities will want to keep the school closed while they respectively conduct their criminal investigation and repair activities while finance officials, concerned about withheld tuition while the school is closed, will want to resume operations more expeditiously. Similarly, in this phase, the public information office’s goal of open and transparent communications may conflict with that of the school’s legal team as the latter awaits the expected slew of liability lawsuits. In short, the various goals and priorities of the stakeholders change over the course of the crisis and may be at variance with each other.

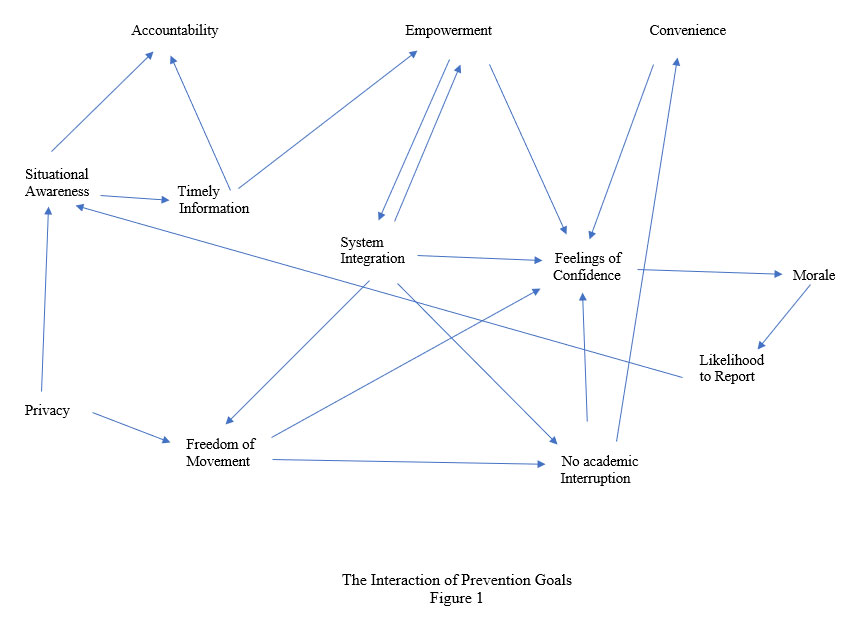

Fourth, and related to the above, schools often fail to specify which of the many actors’ goals are (or should be) ascendant in each phase and how these goals interact with each other. In a dynamic situation, some activities logically precede others and some, though not necessarily the same activities, may have a determining impact on the situation. See Figure 1 for an example of the interaction of goals.

Negative Impacts on Planning

The above fallacies have several deleterious effects on active incident response planning. First and foremost, many stakeholders do not realize they have a role to play. As a result, they have no way of knowing what they need to do in the different phases and what resources they need. Furthermore, they will not practice a responsibility not explicitly assigned to them and so have no way of knowing whether they are deficient and what resources they need to acquire.

Second, they will not understand how their own roles will interact with those of others. Let us consider, for example, the crucial role of parking during the response phase of an active incident. Most schools may have only two or three entrances. In most active incidents, it’s not uncommon to have scores if not hundreds of police cruisers respond. If the entrances and exits are clogged with cruisers, how will medical personnel and ambulances access the scene to provide immediate life-saving care2 and transport victims to hospitals? Are there sufficient school parking services personnel to direct large volumes of vehicles to staging areas and have they practiced this task; or, in an ongoing dangerous situation, is parking even the right solution for this task? If the answer to either of these questions is no, have mutual aid agreements been established with local responders?

Third, in the absence of an appreciation of their respective tasks, various stakeholders will respond in a disjointed rather than coordinated manner. The initiation of such a horrific event is no time to start figuring who’s in charge, what needs to be done, what needs to be done first, and whether the activities of Stakeholder A will have a negative effect upon the success of Stakeholder B’s response?

Overcoming Stovepipes

Most schools, like other task-oriented entities, are hierarchically structured. The individual with overall responsibility and authority (e.g., the principal, provost) is assisted by other department heads who perform specialized tasks, such as teaching academic classes, food services, counseling, maintenance, and administration. Individuals performing these specialized tasks are required to “stay in their lane.” Teachers don’t serve food and maintenance personnel do not keep attendance records. Specialization of tasks results in specialization of information. However, narrowly focused information channels undermine task integration across areas of responsibilities. The resulting isolated fiefdoms have at best a superficial understanding of other stakeholders’ responsibilities and operational plans. In an environment in which their respective perspectives, goals, priorities, and plans are not shared, these various actors will be ill-prepared to interoperate in a crisis.

The first step of developing a multi-phased integrated approach is to conduct a tabletop exercise (TTX) in which senior representatives of all the stakeholders, both internal and external (i.e., municipal law enforcement, medical responders, and hospitals), work through a multi-phase active incident scenario.

The TTX will examine crucial issues such as how each stakeholder will respond in each phase; who serves as back-up if a major player isn’t available; would information be timely, how would it flow, and where are the bottlenecks; what are the respective responsibilities of school administrators relative to first responders; how weather, time of day and other contingencies affect response; scope and effectiveness of existing MOUs; dealing with parents, the media, and political leaders; and best practices and lessons learned from other incidents.

The TTX

The TTX should take several hours, depending on the complexity of the scenario, the number of participants, and whether the exercise covers all phases or just one or two at a time. The scenario should be fully scripted to incorporate real locations, approximate reaction and response times, seasonal weather, realistic estimates of available staffing and students on campus3, etc.

The TTX can be conducted using the following steps:

Step 1: Identify Goals

First, the facilitator should discuss the general school goals that need to be accomplished during the particular phase under consideration. For instance, during the recovery phase, the following 27 selected goals (there are more!) are important4:

- Security of the shooting site(s)

- Privacy of victims

- Timely repairs

- Accountability

- Recovery, documentation and eventual return of abandoned items

- Situational awareness

- Timely information shared with campus community

- Timely information shared within and between leadership

- Freedom of movement on campus

- Access control

- Replacement of lost equipment

- Secure counseling for traumatized individuals

- Development of renewed confidence and feeling of safety

- Cost-effective initiatives

- Timely resumption of academic and administrative functions

- Identification of best practices and lessons learned

- Development of a corrective actions plan, with priorities

- Reconcile lost income and unanticipated expenses with on-going financial needs

- Unified message

- Response to FOIA requests

- Response to VIP visits

- Minimize loss of faculty, students and staff

- Recruitment of lost personnel

- Minimize liability

- Outreach to client base

- Rejuvenation of school brand

- Modification of existing MOUs and development of new ones as needed

This list should be compiled for each crisis phase (i.e., prevention, response, mitigation, and recovery).

Step 2: Identify Goals of Specific Stakeholders

As noted above, different stakeholders have different goals. Continuing with the recovery example, the following breakout for some of the stakeholders5 shows the coincidence and divergence of some of these goals. (There may be as many as 15 (internal and external) stakeholders at the table6.)

The Police

- Security of the shooting site(s)

- Recovery, documentation and eventual return of abandoned items

- Situational awareness

- Timely information shared within and between leadership

- Access control

- Secure counseling for traumatized individuals (including responders)

- Development of renewed confidence and feeling of safety

- Replacement of lost/destroyed equipment

- Identification of best practices and lessons learned

- Development of a time-phased corrective actions plan, with priorities and assigned responsibilities

- Response to FOIA requests

- Response to VIP visits

- Minimize liability

- Modification of existing MOUs and development of new ones as needed

Facilities

- Timely and cost-effective repairs

- Timely information shared within and between leadership

- Freedom of movement on campus

- Access control

- Secure counseling for traumatized individuals

- Cost-effective initiatives

- Minimize loss of faculty, students, and staff

- Recruitment of lost personnel

Public Information Office

- Privacy of victims

- Situational awareness

- Timely information shared with campus community

- Timely information shared within and between leadership

- Development of renewed confidence and feeling of safety

- Timely resumption of academic and administrative functions

- Identification of best practices and lessons learned

- Development of a corrective actions plan, with priorities

- Unified message

- Response to FOIA requests

- Response to VIP visits

- Minimize liability

- Outreach to client base

- Rejuvenation of school brand

Students

- Privacy of victims

- Recovery, documentation and eventual return of abandoned items

- Situational awareness

- Timely information shared with campus community

- Timely information shared within and between leadership

- Freedom of movement on campus

- Access control

- Secure counseling for traumatized individuals

- Development of renewed confidence and feeling of safety

- Timely resumption of academic and administrative functions

- Rejuvenation of school brand

Step 3: Identify Priorities for Each Stakeholder

Stakeholders must prioritize their respective tasks. Considering the police, for instance, some tasks precede others (e.g., security of the shooting scene is a prerequisite to access control and both must be accomplished before development of the corrective actions plan and modifications of MOUs); and from the police perspective, others are simply lower on the food chain of importance, such as responding to FOIA requests (a high priority for the PIO), replacing lost equipment and school liability considerations). In the same manner, prioritized lists of goals (and their associated tasks) need to be developed for each stakeholder in each phase.

Note that some priorities of certain stakeholders may outweigh those of another, so the process must include mutual agreement of each stakeholder with the others’ rankings.