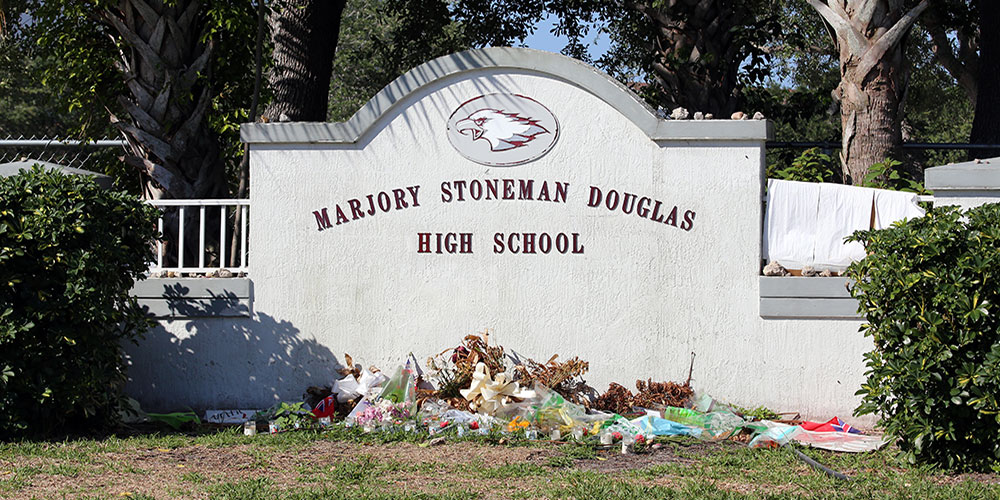

For the first time since last September, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission met on Tuesday to discuss various school safety issues and to assess the effectiveness of programs and laws implemented after the tragedy.

The commission, which was created to investigate the Feb. 2018 shooting and make safety recommendations, discussed the need for more consistent guidelines that schools can follow to prevent dangerous incidents, reports CBS News.

“One of the things that I know works is, when you’re training people, you’ve got to give them as hard and fast rules as you can. People like hard and fast rules,” said Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, who is chairman of the commission. “You have to minimize the subjectivity, you’ve got to give them that framework.”

While all public schools in the state of Florida use the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines, they don’t have a common reporting system. According to a survey distributed by the commission to Florida school districts, 18 districts use dedicated software systems provided by four vendors, two have developed their own systems, 21 are using “some aspects of their student information systems,” nine are using “pen and paper,” and 14 are using Excel, Google Docs or similar software.

“Five hundred and thirty schools, 350,000 students, they reported to the office of Safe Schools that they did 277 threat assessments for the 2020 – 2021 school year,” said Gualtieri. “That is 0.8 threat assessments per one thousand students. That’s not even one per school.”

Gualtieri said Broward County Public Schools, which houses MSD, has improved their threat management and assessment processes, describing them as “a model for the way it should be done.” Superintendent Dr. Vickie Cartwright said the district’s board approved the creation of a new behavioral threat assessment department under the safety, security, and emergency preparedness division.

Broward County Sheriff Gregory Tony also testified about improvements his agency has made in emergency communications. Since he raised salaries, Tony said BSO has been able to fulfill a staffing shortage among dispatchers and 911 operators, according to NBC.

“We learned from MSD about the importance of dispatching resources and getting enough personnel out there fast, swiftly, without having to make multiple calls,” he said.

Responding law enforcement officers from various agencies had difficulties communicating with each other at the scene. When BSO deputies and Coral Springs Police Department officers arrived, they were unable to merge radio traffic. Coral Springs firefighter Mike Moser said all first responders in the county can now communicate with each other on a predetermined radio channel reserved for large incidents.

However, Tony voiced frustration over the fact that 911 calls from Parkland are still routed through Coral Springs. He wants his agency to run the system entirely, Local10 reports.

“(We) cannot get past the bureaucratic structure of government that exists with two different entities and non-elected officials on one side, a single elected sheriff and then a county administrator,” Tony said. “It didn’t work that way in the past. This organization has managed communications, handled it effectively, had built it. There was a transition into a regional program, so to speak.”

Tony and Cartwright are also working together on implementing real-time viewing of surveillance cameras on school campuses and geocoding that will help determine where an emergency is happening.

MSD Public Safety Commission Discusses Guardian Program, Alyssa’s Law

During the meeting, Gualtieri pushed for more districts to implement the Coach Aaron Feis Guardian Program, a program recommended in the commission’s initial report.

Guardians are armed personnel who are either school employees who agree to serve in addition to their regular job duties or personnel hired for the specific purpose of serving as a guardian, according to WTPS. Guardians must complete 144 hours of training and pass psychological and drug screenings.

Gualtieri said there should be more than a single armed person on each campus, which is what is required under current law.

“Two is better than one, three is better than two and four is better than three,” he said. “That doesn’t mean you need 50 or 60, but you need to increase security in a measured way.”

Since its enactment, 47 out of 67 school districts participate in the program and approximately 1,300 staff serve as guardians.

Alyssa’s Law was also a topic of discussion. The law requires all Florida public schools to implement a mobile panic push button system that is directly linked to law enforcement to ensure real-time coordination between responding agencies.

Although it was meant to be implemented by the 2021-22 school year, not all districts have it fully in place due to integration issues where the alert doesn’t reach 911.

“As we sit here today now two weeks out from school starting we cannot say with 100% certainty that every district has implemented Alyssa’s Alert so that if you push the button… it is going to the 911 center. We don’t know that for sure,” Gualtieri said. “With the state spending 8 million bucks on this, and the law saying that it had to be done by the end of the school year that just passed, I mean why are we now at that we don’t know.”

Sylvia Ifft, deputy director of emergency management for the Florida Department of Education, said testing is being done over the next few weeks. More testing has been needed than was anticipated, she added.