In Part 1 of this three-part series, the authors discuss common deception strategies school shooters have used to evade detection.

Part 2 covers behavioral differences in K-12 and college shooters’ interactions with parents, peers, and teacher.

Part 3 covers proposed interventions for campus violence prevention.

While school violence in the U.S. has always been a concern, the escalation of threats in K-12 schools and in higher education has strained law enforcement and safety resources to new levels. For example, more than 700 students were arrested in Georgia for issuing threats in the aftermath of the September 2024, Apalachee High School shooting in Winder, Ga.

Anonymous threats delivered via social media have become especially prevalent, leading to school closures, lockdowns, and heightened anxiety over the potential of attacks. While the overwhelming number of threats never materialize into actual violence, their sheer volume creates a culture of fear, disrupts the educational environment, and depletes law enforcement resources.

The rise in communicated threats of violence directed at schools adds yet another dimension to the myriad challenges already facing threat assessment teams, campus police, school resource officers, and law enforcement who must sift through the crushing noise to identify true potential threats.

RELATED: 70% of School Shooters Perpetuated Violence Against Women, Lehigh Study Finds

This same challenge often extends to parents, teachers, and peers, collectively known as bystanders, who struggle to determine whether their child, student, or friend is contemplating violence or is perhaps just experiencing normal young adult phases of development. This dilemma isn’t surprising: even trained threat assessment professionals must engage in a deliberative, structured, and sometimes complicated process to identify persons who are truly on a pathway to violence versus those who are not.

Adding to the difficulty for both professionals and bystanders, attackers continue to actively adapt their methods, conceal their plans, influence, and in some cases, manipulate those around them prior to the attack to escape detection. As bystanders and threat assessment professionals work to better identify potential attackers before they strike, it is important to remember that this is not a static or algorithmic process but a dynamic effort in response to an ever-evolving challenge.

The FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit

The FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU), located in Quantico, Va., continues to hold the primary responsibility within the U.S. federal government for operational engagement and academic research into targeted violence prevention and response. Unlike other government or research entities, the FBI’s BAU is the only national team providing operational support, conducting research using reliable law enforcement records (versus open-source data), and responding to completed mass attacks to conduct post-attack analyses to assess and determine offender motivational drivers.

These “deep dive” post-attack analyses yield useful insights to inform future prevention efforts. As a result, BAU profilers, analysts, and researchers who study, interview, and respond to mass attackers have a distinct advantage in understanding active shooters’ behaviors.

How School Shooters Manipulate Bystanders

While much attention has rightly been focused on attackers’ pre-attack warning signs, another area for exploration is how attackers influence and even manipulate bystanders in the lead-up to their attacks. Time and again, the BAU has observed instances where family members, peers, and teachers witnessed changes in behavior, expressed concerns, and even confronted the offender before the attack.

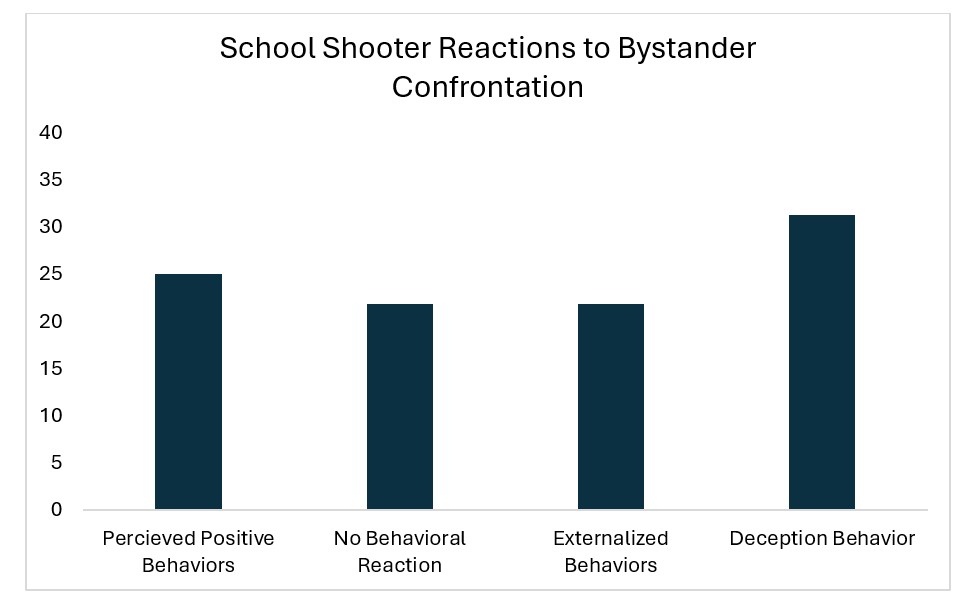

In reviewing 20 school shootings that occurred between 2002 and 2018 (nine at universities or community colleges, and 11 at K-12 schools), the BAU assesses that these shooters utilized nine different methods of manipulation, obfuscation, or disengagement when a bystander directly communicated their concerns. The BAU broadly grouped the ten distinct responses under four general categories as:

- “Perceived positive behaviors” such as impression management, reassurances, or placations;

- “No behavioral reaction” such as ignoring or unresponsiveness to confrontations;

- “Externalized behaviors” such as blaming others or becoming aggressive; and

- “Deception behavior” where the shooter actively created a false narrative and/or lied to conceal their contemplated or planned violent act.

Reactions of school shooters (n = 20) when confronted with bystanders’ concerns or questions based on categories of behaviors. School shooters category appeared to utilize deceptive behaviors the most compared to other behaviors.

Leveraging FBI/BAU research data and operational experience, the BAU authors present here practical considerations for improving bystander intervention, school/campus threat assessment, and law enforcement engagement. Understanding the nuances of these tactics, and particularly how they appear to vary in different social contexts, is critical for cultivating opportunities for detection and disruption.

Deception Strategies for Evading Detection

Over the past decade, significant advances have been made in understanding the behaviors of violent offenders prior to their attacks. One example, where the attackers were all active shooters, is the FBI’s 2018 A Study of the Pre-attack Behaviors of Active Shooters in the United States Between 2000 and 2013. This study offered valuable insights into how active shooters responded when confronted by family, friends, and authority figures who observed concerning behaviors prior to the attack.

Analyzing 63 cases of active shooters, one of the study’s key findings focused on bystander responses to warning behaviors:

- 83% of the shooters in the study had at least one bystander confront them or express concern about one or more of their behaviors;

- 54% of the shooters in the study displayed at least one concerning behavior that received no response or reaction from anyone.

Importantly, every shooter in the study exhibited at least one observable concerning behavior, and most displayed four to five such behaviors. These findings underscore a core challenge: while concerning pre-attack behaviors are often observed by others, bystanders frequently don’t know how to respond in a meaningful way or, in some cases, choose not to respond at all.

Though not systematically measured, the BAU anecdotally noted that several of the shooters in the study who were confronted by a bystander manipulated or influenced their way out of the conversation, deflecting concern and avoiding further scrutiny. These tactics may have assisted the shooter in evading detection on their pathway to the shooting attack.

The Psychology of Deception in Adolescents

Related research from fields such as deception detection, forensic linguistics, and threat assessment can provide additional insights into the strategies utilized by shooters.

Deception, defined as intentionally causing someone to believe something untrue (Buller & Burgoon, 1996), and evasion, the avoidance of giving direct or complete responses (Masip et al., 2017), play a particularly important role. Behaviors involving deception and evasion are routinely observed in adolescence, especially during the developmental stage where individuals navigate autonomy and identity while still influenced by parental and peer expectations (Goffman, 1959).

RELATED: 3 Ways to Prevent Youth Violence

Adolescence and young adulthood are pivotal phases of development, marked by identity formation, peer influence, and the gradual assertion of autonomy from parental figures (Arnett, 2000). During these stages of development, deceptive behaviors can often serve as tools to avoid conflict, protect privacy, or gain social standing. Goffman’s theory of self-presentation adds further context, suggesting that individuals perform different roles and adopt temporary personas depending on their social environment.

Adolescents, transitioning into adulthood, can become increasingly adept at using deceptive behaviors to manage their public image. This becomes particularly evident in interactions with parents, teachers, and peers, where the desire for social approval can be especially pronounced.

Common Deception Strategies Used by Adolescents

Understanding the common strategies of deception and evasion frequently employed by adolescents can be useful when assessing the risk for violence in school-aged individuals:

- Lying by omission: Adolescents will sometimes withhold information to prevent conflict or avoid repercussions, particularly in their communications with parents and authority figures. This form of deception is subtle and often goes unnoticed, as it involves leaving out critical details rather than fabricating false information (Engels et al., 2006).

- Minimization: Another common tactic is minimizing the severity of an action or event, enabling an individual to downplay their behavior, particularly when confronted by peers or authority figures. By framing a situation as less serious than it is or as an expected phase of the adolescent experience, an individual can evade accountability and preserve social standing (Marshall et al., 2005).

- Vagueness and ambiguity: Individuals use vague language to avoid making firm commitments or admissions. This strategy is particularly effective in conversations where a person seeks to avoid lying outright but simultaneously does not wish to fully disclose the truth (Vrij et al., 2010).

- False compliance: Individuals may express cooperation and agreement when confronted or directed, only to secretly defy it when out of sight of authority figures. This strategy can be utilized in both school and home environments and serves as a means of preserving autonomy while avoiding immediate conflict (Smetana et al., 2009).

- Denial: Adolescents may outright deny any violent intentions, claiming they have been misunderstood or that their behavior has been misinterpreted. This denial tactic is often employed in interactions with teachers or other authority figures who are likely to perceive the behavior as a serious concern.

- Intimidation or aggression: In the experience of the BAU, some individuals contemplating targeted violence, when confronted by concerned bystanders, may react with hostility, often demanding that others back off and “mind their own business.” Intimidation and threats of retribution can be tactics used to deflect attention and are ultimately designed to conceal the problematic behavior, which could include a planned attack.

The ‘Non-Barking Dog’ Theory

Aldert Vrij’s “non-barking dog” theory, introduced in 2010, provides another useful framework for understanding deception and evasion in this context, particularly when individuals strategically withhold expected behaviors to avoid suspicion.

Drawing inspiration from a Sherlock Holmes story in which the absence of a dog’s bark signaled something unusual, Vrij argues that the lack of expected behaviors or emotional responses can serve as crucial indicators of deceit. This theory may be particularly relevant to mass attackers, who often compartmentalize plans of attack, self-regulate emotions, and engage in image control to appear calm, detached, or otherwise normal in the lead-up to violence, thus disarming potential observers who might otherwise intervene. These future attackers may consciously avoid the emotional or behavioral cues typically associated with internal conflict or aggression, such as agitation, anxiety, or erratic behavior. The absence of pronounced distress or blatantly concerning signals (“non-barking behavior”) can deceive friends, family, or colleagues who might otherwise respond by raising concerns with authority figures.

Comparing School Shooters to Persons of Concern

To further explore this issue, the BAU conducted a limited comparative analysis of school shooters (n=20) against a matched sample of persons of concern (POCs, n=20) who exhibited disturbing behaviors but did not escalate to violence. The results suggest a potentially significant psychological and behavioral divergence between these two groups.

Qualitative findings indicate that POCs who did not attack tended to exhibit heightened emotional volatility, which manifested as more overt, attention-grabbing behaviors, often described as making more “noise” in comparison to school shooters. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this increased “noise” and emotional expressiveness appeared to generate interest and draw greater scrutiny from authority figures, including educators and mental health professionals. As a result, POCs more frequently become the subject of early intervention efforts, whether through the provision of mental health services or the implementation of disciplinary measures.

RELATED: How Common Are Female School Shooters?

An important caveat: it was not that the POCs in this sample were more emotional and therefore less dangerous, but rather, their emotional volatility or “noisiness” resulted in them being noticed and referred for intervention, often through the behavioral threat assessment and management (BTAM) process. Furthermore, peer reporting plays a critical role in this process, as POCs are more likely to be flagged by their peers, leading to formal reports to school administration and subsequent involvement of law enforcement. This suggests that the visibility of emotional dysregulation and externalized behaviors in POCs may counterintuitively serve as a protective factor by triggering early detection and intervention, potentially averting the escalation to violence.

Conversely, the more controlled, less conspicuous, and in some cases deliberately obfuscated behaviors of school shooters may allow them to evade similar levels of intervention, thus complicating efforts to preemptively mitigate the risk they pose.

About the Authors

Dr. Karie Gibson earned a Doctor of Psychology (Psy.D.) degree in clinical psychology with a concentration in forensics. She has been a special agent with the FBI for more than 19 years and currently serves as the Unit Chief for the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit-1 (BAU-1), which focuses on the prevention of terrorism and targeted violence.

Dr. Lauren Brubaker is the Behavioral Research Scientist at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. She manages research projects for BAU-1, the Behavioral Threat Assessment Center, and BAU-2, the Cyber Behavioral Analysis Center.

Andre Simons, CTM, is a retired FBI Supervisory Special Agent and a Contract Researcher to the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit.

Note: The views expressed by guest bloggers and contributors are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, Campus Safety.

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480.

- Buller, D. B., & Burgoon, J. K. (1996). Interpersonal deception theory. Communication Theory, 6(3), 203-242.

- Engels, R. C., Finkenauer, C., & van Kooten, D. C. (2006). Lying behavior, family functioning and adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(6), 949-958.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The moral career of the mental patient. Psychiatry, 22(2), 123-142.

- Marshall, S. K., Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Bosdet, L. (2005). Information management: Considering adolescents’ regulation of parental knowledge. Journal of adolescence, 28(5), 633-647.

- Masip, J., Martínez, C., Blandón-Gitlin, I., Sánchez, N., Herrero, C., & Ibabe, I. (2017). Learning to detect deception from evasive answers and inconsistencies across repeated interviews: A study with lay respondents and police officers. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2207.

- Silver, J., Simons, A., & Craun, S. (2018). A study of the pre-attack behaviors of active shooters in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- Smetana, J. G., Villalobos, M., Tasopoulos-Chan, M., Gettman, D. C., & Campione-Barr, N. (2009). Early and middle adolescents’ disclosure to parents about activities in different domains. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 693-713.

- Vrij, A., Granhag, P. A., & Porter, S. (2010). Pitfalls and opportunities in nonverbal and verbal lie detection. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(3), 89-121.