Using research conducted by the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) and other sources, Part 1 of this three-part series discussed common deception strategies school shooters have used to evade detection.

Part 2 below discusses common behavioral differences seen in K-12 and college shooters’ interactions with those around them.

Part 3 discusses proposed interventions for campus violence prevention.

Drawing upon both research and operational experience, the BAU has observed that school shooters may adjust their behaviors and modify their manipulations depending on the social context and the relationship they have with the bystander. Parents, peers, and educators/teachers represent three distinct yet common categories of interpersonal relationships, each with unique dynamics that influence how school shooters manipulate their responses.

The BAU notes the differences between K-12 and college shooters in these contexts as particularly striking (For the purposes of this paper, a K–12 school shooter is defined as a current or former student of a K–12 school who carried out a targeted attack at that school. Similarly, a college shooter is defined as a current or former college student who carried out a targeted attack at a college or university.)

K-12 School Shooters Often Exploit Emotional Investments

In the K-12 setting, school shooters tend to be under the age of 18, reside with parents or with a caregiver, and thus have more frequent and/or substantive interactions with adults and authority figures. In this context, adolescents may generally be more likely to deceive or evade when they perceive their parents or authority figures as overly controlling or punitive (Smetana et al., 2009).

RELATED: Preventing Active Shooter Incidents Through Student Behavior Analysis

Deception and evasion can become tools for asserting independence while avoiding direct confrontation or punishment. Moreover, adolescents are more likely to use deceptive strategies with parents than with peers, as peer relationships are often characterized by higher levels of trust and equality (Marshall et al., 2005).

The ‘Code of Silence’ Among Peers

Peers often experience conflicting emotions between suspicions of imminent violent behavior and the implicit “code of silence” that frequently governs adolescent and young adult peer relationships. This code, characterized by a reluctance to report or “snitch” on a friend, can frequently supersede concerns about potential future violence. Even when peers observe concerning behaviors, their willingness to act can be diminished by a fear of social repercussions, including ostracization or damage to their personal relationships (Ajzen, 1991; Brown, Clasen, & Eicher, 1986).

Compounding this dilemma is the inherent uncertainty that peers face in assessing the severity of a threat. Lacking the necessary training, confidence, or expertise to definitively interpret observed behaviors as precursors to violence, peers may doubt their own judgment, further inhibiting their willingness to report their friend to an authority figure. Research has shown that in ambiguous situations, bystanders are typically more likely to defer action due to the diffusion of responsibility and the fear of making incorrect assessments (Darley & Latané, 1968), commonly referred to as “the bystander effect”. Thus, the interplay between social loyalty, the “bystander effect”, and overall uncertainty of future violence can create a significant barrier to early intervention in cases where peer observation could be instrumental in preventing attacks.

How K-12 Shooters Conceal Their Plans

A K-12 school shooter who is an adolescent living with parents or other authority figures must evade detection of behavioral changes, regulating the image they project to others while concurrently concealing the necessary instruments (e.g., weapons, ammunition) and/or plans to enable the attack. In the experience of the BAU, school shooters often mask their grievances and contemplated use of violence through minimization (e.g., “It’s nothing, I’m just having a bad day”), making excuses for their concerning behaviors, attributing them to common adolescent issues like stress, reclusiveness, or academic pressure.

Strong emotional attachments may lead parents or others close to accept explanations that are implausible and to dismiss their own suspicions. This process is shaped by confirmation bias, which is the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that supports preexisting beliefs or hypotheses while discounting contradictory evidence (Nickerson, 1998). Such bias helps explain the “bystander paradox:” those who are physically and emotionally closest to a potential school shooter, and thus best positioned to observe concerning behaviors, are often the least able or willing to recognize their seriousness and/or report them to authorities.

This paradox is, in many ways, an understandable and logical human response. What parent, close friend, or trusted mentor would readily or eagerly entertain the idea that someone they love could be capable of mass violence? The same emotional bond that places them in a position to observe concerning behaviors can also cloud their ability to recognize or act on them.

The bystander paradox doesn’t always reflect indifference, but more commonly highlights the tension between love, loyalty, and the growing sense that something might be very wrong. For many bystanders, that internal conflict can lead to hesitation, minimization, or even silence.

College Shooters: Navigating Isolation and Mental Health Struggles

In contrast, students who are enrolled in colleges or universities often face far different circumstances. Older, increasingly self-sufficient, and typically more isolated, these individuals may live off-campus and have fewer close relationships. They are increasingly more likely to suffer from untreated mental health issues (Blanco et al., 2008), and the opportunity to “cocoon” in solitude can make it difficult for others to detect subtle or even overtly obvious pre-attack behaviors.

Decreased attention and limited interactions by family is normalized due to the natural separation that occurs when young adults seek out placement with higher education. However, these students still interact with professors, roommates, or peers who can observe changes in behavior.

RELATED: Building a School Safety Culture on Campus and in Your Community

In higher education, the dynamics shift as students can choose to adopt a more detached and individualistic social posture. College peers, influenced by developmental changes and an increased emphasis on autonomy, are less likely to intervene in behaviors they perceive as reflective of personal/emotional challenges or academic stress. This detachment is exacerbated by social norms that discourage “interfering” in others’ lives, thus creating a permissive environment in which warning signs are more easily ignored (Bonino et al., 2005).

Potential attackers can exploit this detachment by downplaying concerning behaviors, minimizing them as harmless expressions of frustration related to academic pressures, personal difficulties, or other transitory issues. Such rationalizations serve to reduce the perceived threat and mitigate the likelihood of peer intervention (DeLisi et al., 2018).

Concealment Tactics in Higher Education

College shooters can conceal their planned attacks in ways that differ from their younger counterparts. Whereas K-12 school shooters might rely on emotional bonds to reassure parents and teachers, college shooters are more likely to exploit their peers’ detachment, play upon themes of independence and individuality, and push others to accept the claim that young adults can and should manage their own affairs. Their behaviors often include withdrawal from social activities, declines in academic performance, or disturbing social media posts. These warning signs are often rationalized as typical stressors and “growing pains” associated with assimilation into college life.

For example, the shooter who targeted faculty and students at Virginia Tech in 2007, exhibited several warning signs, including increased social isolation and alarming communications. The gunman was able to avoid detection in part by maintaining a low profile and by deflecting concerns raised by faculty and peers. His behavior comported in some ways with Vrij’s non-barking dog theory in that there was an absence of overt or “noisy” aggression that might have raised additional alarms, even though significant signs of distress were present.

The Role of Teachers in Detecting Warning Signs

The BAU has observed that the overwhelming volume of students and behaviors that teachers must manage can make it difficult for them to detect the fleeting, nuanced, or subtle pre-attack behaviors, often referred to as “leakage.” While teachers play a critical role in maintaining school safety, they are frequently tasked with addressing a wide array of student needs, behavioral challenges, and administrative responsibilities. Teachers are not only educators but also disciplinarians, counselors, and mentors, often balancing these roles simultaneously. Given these demands, expecting teachers to consistently identify subtle, individualized signs of potential violence can be unrealistic without proper support, training, and resources.

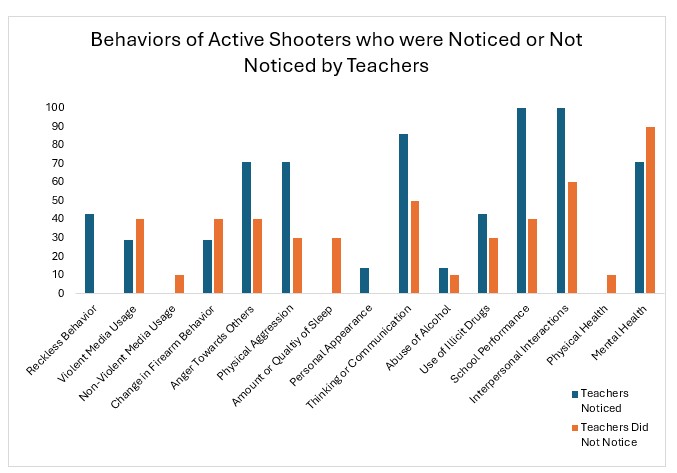

Through this lens, it’s not surprising that the pre-attack behaviors most observed by teachers are those related to interactions and relationships with others (e.g., anger, physical aggression, and interpersonal conflicts) as well as performance-based indicators (e.g., academic performance, thought processes, verbal expressions, or communications that suggested a break from typical or coherent reasoning).

Pre-attack behaviors of school shooters that teachers noticed and pre-attack behaviors of school shooters that teachers did not notice (n = 20). K-12 teachers and college professors both appeared to notice changes in interpersonal interactions and mental health, followed by school performance issues, decreases in quality of communication or thinking, and anger towards others.

How Attackers Evade Teacher Detection

Teachers, particularly in K-12 environments, are often called upon to identify and respond to behaviors of concern, such as aggression, social withdrawal, or threats of violence. However, attackers can often manage to evade detection by presenting a façade of compliance or of reform. In many cases, they acknowledge past misbehavior while simultaneously offering reassurances that they are “working on themselves” or “trying to improve.” This tactic, observed in several high-profile cases, including the perpetrator of the Parkland shooting, appears to fall within the category of responses identified by the BAU as “perceived positive behaviors” or “false compliance.”

RELATED: Early Warning Signs of Potential School Gun Violence

The BAU has further observed that in general, teachers will report the concerning behaviors to school officials or parents if they believe disciplinary action is warranted. If teachers do not believe disciplinary action is warranted, they tend to confront the individual directly or manage the situation within the confines of the classroom. It may be difficult for teachers – overwhelmed by the enormous challenges of day-to-day classroom management – to not only address the problematic behavior but also to explore why the problematic behavior is happening.

Challenges in Higher Education Settings

In higher education settings, the challenge for faculty and administrators is further complicated by the increasing autonomy granted to students. College students, typically viewed as adults, are often given the benefit of the doubt in matters of personal behavior, and the large number of students in many college classes may dilute the quantity and quality of interactions between students and instructors. Faculty may be less attuned to or less inclined to report concerning behaviors unless they directly disrupt the academic environment.

Further, family members sometimes lack access to information about their student’s academic adjustment and progress due to privacy laws that recognize students as independent adults. This detachment, combined with the larger and more impersonal nature of many college settings, can allow attackers to blend in more easily, evading detection until it’s too late (Fox & DeLateur, 2014).

Peer Interactions and the Pathway to Violence

In both K-12 and higher education contexts, then, peer interactions may represent a critical yet underutilized arena for the detection of pre-attack behaviors exhibited by potential attackers. Peer groups are uniquely positioned to observe the day-to-day actions, emotional volatility, and social withdrawal that often precede acts of violence. However, despite their proximity, peers frequently neglect to report concerning behaviors, a phenomenon likely shaped by several socio-psychological factors and once again reflecting the bystander paradox.

In K-12 settings, peers may interpret aggressive or threatening behavior through the lens of adolescent development, normalizing it as part of the broader spectrum of teenage rebellion. Such behaviors are often trivialized, framed as “jokes” or dismissed as inconsequential outbursts that do not actually suggest true violent intent. This interpretation aligns with findings in adolescent psychology, where peers are more likely to downplay threats due to the perceived omnipresence of dramatic emotional expressions during adolescence (Saarni et al., 2006).

The BAU posits that when concerning behaviors are observed by both teachers AND peers, the likelihood of intervention to address the issue and mitigate the potential threat significantly increases. Conversely, when such behaviors are noticed by only one group, the probability of intervention diminishes, reducing the chances of effectively managing the potential for violence.

About the Authors

Dr. Karie Gibson earned a Doctor of Psychology (Psy.D.) degree in clinical psychology with a concentration in forensics. She has been a special agent with the FBI for more than 19 years and currently serves as the Unit Chief for the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit-1 (BAU-1), which focuses on the prevention of terrorism and targeted violence.

Dr. Lauren Brubaker is the Behavioral Research Scientist at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. She manages research projects for BAU-1, the Behavioral Threat Assessment Center, and BAU-2, the Cyber Behavioral Analysis Center.

Andre Simons, CTM, is a retired FBI Supervisory Special Agent and a Contract Researcher to the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit.

Note: The views expressed by guest bloggers and contributors are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, Campus Safety.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Blanco, C., Okuda, M., Wright, C., Hasin, D. S., Grant, B. F., Liu, S. M., & Olfson, M. (2008). Mental health of college students and their non–college-attending peers: results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(12), 1429-1437.

- Bonino, S., Cattelino, E., and Ciairano, S. (2005). Adolescents and risk: Behavior, functions, and protective factors. New York: Springer.

- Brown, B. B., Clasen, D. R., & Eicher, S. A. (1986). Perceptions of peer pressure, peer conformity dispositions, and self-reported behavior among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 22(4), 521-530.

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4), 377-383.

- DeLisi, M., Tostlebe, J., Burgason, K., Heirigs, M., & Vaughn, M. (2018). Self-control versus psychopathy: A head-to-head test of general theories of antisociality. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 16(1), 53-76.

- Fox, J. A., & DeLateur, M. J. (2014). Mass shootings in America: Moving beyond Newtown. Homicide Studies, 18(1), 125-145.

- Gibson, K. A., Craun, S. W., Ford, A. G., Solik, K., & Silver, J. (2020). Possible attackers? A comparison between the behaviors and stressors of persons of concern and active shooters. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 7(1-2), 1-12.

- Marshall, S. K., Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Bosdet, L. (2005). Information management: Considering adolescents’ regulation of parental knowledge. Journal of adolescence, 28(5), 633-647.

- Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175-220.

- Saarni, C., Campos, J. J., Camras, L. A., & Witherington, D. (2006). Emotional development: Action, communication, and understanding. Handbook of Child Psychology, 3, 226-200.

- Smetana, J. G., Villalobos, M., Tasopoulos-Chan, M., Gettman, D. C., & Campione-Barr, N. (2009). Early and middle adolescents’ disclosure to parents about activities in different domains. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 693-713.

- Vrij, A., Granhag, P. A., & Porter, S. (2010). Pitfalls and opportunities in nonverbal and verbal lie detection. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(3), 89-121.