Using research conducted by the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) and other sources, Part 1 of this three-part series discussed common deception strategies school shooters have used to evade detection, and Part 2 discussed common behavioral differences seen in K-12 and college shooters’ interactions with those around them.

Part 3 below highlights proposed interventions for campus violence prevention.

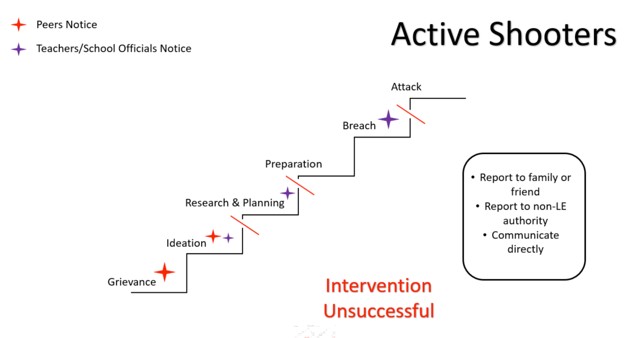

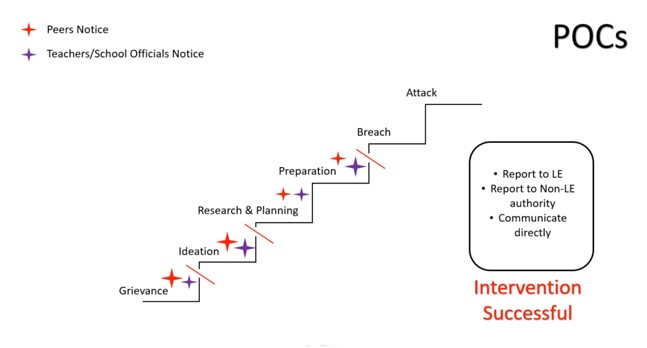

It can be helpful to compare the timing of interventions by teachers and peers in response to concerns as they occurred along the “pathway to violence.” (Fein & Vossekuil, 1998; Calhoun & Weston, 2003). This theoretical framework delineates the sequence of behaviors and psychological processes leading an individual from an initial grievance to the actual commission of a violent act.

The pathway involves a progression of observable steps that potential attackers often exhibit, beginning with grievance formation, followed by ideation, research and planning, preparation, breach, and ultimately, the implementation of violent actions. Individuals might not progress linearly through these stages. Intervention at any point can effectively mitigate the risk. Research on this model has demonstrated that 58% of the time all the steps of the pathway to violence remained intact and observable for active shooters (Jones, et al., 2024).

Visual of when behaviors are noticed on the Pathway to Violence for school shooters, who notices those behaviors, and what is done when those behaviors are noticed. For active shooters, behaviors tend to be noticed by authority figures much later in the Pathway and much less often compared to persons of concern (POCs). The larger the star, the more individuals notice the behavior. Active shooters appear to be better at evading detection and bystander concern.

4 Interventions for Campus Violence Prevention

To address the challenge of attackers’ influence and manipulation, it is essential to develop strategies that enhance bystander intervention and improve threat assessment protocols. Several key interventions are proposed:

- Enhanced Bystander Training: Training programs in K-12 and higher education settings should focus on teaching parents, peers, and teachers how to recognize pre-attack behaviors and persist in their inquiries, even in the face of resistance, deception, or evasion. As shooters have demonstrated, they often exploit emotional bonds to manipulate suspicious bystanders away from their inquiries. By understanding the specific tactics used by shooters to influence those around them, bystanders can be better equipped to respond effectively and with tenacity.

- Multi-Disciplinary Threat Assessment Teams: Schools and workplaces should establish threat assessment teams that include law enforcement, mental health professionals, and educators. These teams can provide a comprehensive approach to evaluating and addressing concerns about potential violence and can also evaluate whether a person of concern is actively working to obfuscate violent intent and/or evade detection.

- Advanced Law Enforcement Training: Law enforcement officers, behavioral health specialists, and school resource officers should receive specialized training to recognize and respond to deception and evasion tactics employed by individuals who may be contemplating violence. This training should emphasize understanding the communication strategies used by potential offenders and developing effective countermeasures during interactions with law enforcement. Additionally, threat assessment interviewing techniques may prove valuable in identifying any progression along the pathway to violence.

- Established Clear Reporting Process: Making it clear for bystanders when you see concerning behaviors that could be determined to be pre-attack behaviors, what are the recommended steps to follow for reporting is important (See more at the FBI’s Prevent Mass Violence Campaign – Prevent Mass Violence — FBI). More is needed to prevent mass violence than communicating directly with the potential attacker. Telling someone trustworthy the concerns observed is important, especially when reporting to law enforcement is not an option. Further, for our schools and workplaces, if someone reports concerning behaviors, having a process that has consistent follow through in a manner that protects the reporting party, and the person of concern’s personal circumstances in a respectful manner is key for long-term prevention efforts.

Creating Safer Educational Environments

When looking a specific subset of mass attackers, active shooters were determined to often exploit the emotional bonds they share with parents, peers, and teachers to conceal their intentions and evade detection. By understanding the specific tactics, used to manipulate these relationships, more effective strategies for preventing future attacks can be developed. Additionally, the rise in communicated threats to schools presents new challenges for educators and law enforcement, requiring updated protocols and enhanced threat assessment tools.

RELATED: 4 School Security Basics Your Campus Should Implement Now

Enhanced bystander training, multi-disciplinary threat assessment teams, advanced law enforcement training, and established reporting processes are critical components of a comprehensive approach to long-term violence prevention. By improving the ability of individuals and institutions to recognize and respond to warning signs early, safer environments for students and staff can be created, reducing the likelihood of both threats and actual violence.

About the Authors

Dr. Karie Gibson earned a Doctor of Psychology (Psy.D.) degree in clinical psychology with a concentration in forensics. She has been a special agent with the FBI for more than 19 years and currently serves as the Unit Chief for the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit-1 (BAU-1), which focuses on the prevention of terrorism and targeted violence.

Dr. Lauren Brubaker is the Behavioral Research Scientist at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. She manages research projects for BAU-1, the Behavioral Threat Assessment Center, and BAU-2, the Cyber Behavioral Analysis Center.

Andre Simons, CTM, is a retired FBI Supervisory Special Agent and a Contract Researcher to the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit.

Note: The views expressed by guest bloggers and contributors are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, Campus Safety.

References

- Fein, R. A., & Vossekuil, B. (1998). Protective intelligence and threat assessment investigations: A guide for state and local law enforcement officials. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

- Calhoun, F. S., & Weston, S. W. (2003). Contemporary threat management: A practical guide for identifying, assessing, and managing individuals of violent intent. Specialized Training Services.

- Jones, N. T., Williams, M. M., Cilke, T. R., Gibson, K. A., O’Shea, C. L., & Gray, A. E. (2024). Are all pathway behaviors observable? A quantitative analysis of the pathway to intended violence model. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 12(2), 106-115.