Much of today’s focus regarding K-12 school safety and security is on emergency response. Various stakeholders, including district leaders, parents, and school boards, want to know if a school is prepared to respond to an incident, particularly those involving violence.

However, prevention should be at the forefront of the rhetoric and school safety plans, and behavioral threat assessments play a pivotal role.

The overall threat landscape has drastically changed in recent years. During the pandemic, the United States saw a significant uptick in homicides, shootings, and aggravated assaults. While FBI crime data shows overall violent crime returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, the Justice Department’s National Crime Victimization Survey found violent victimization rate for people between the ages of 12 and 17 doubled, representing the age group that saw the biggest increase in violent victimization. The survey also found fatal and non-fatal gun violence increased by more than 10% for those under the age of 18.

Campus Safety spoke with Lew Robinson, a retired U.S. Secret Service who specialized in behavioral threats assessments, and Kirk Cerny, COO of Secure Passage, about what is causing an increase in violent crime among young people and leading practices and resources for addressing the issue.

“We’ve really lost trust and respect in each other, trust and respect in our institutions — whether it be governmental schools and so forth. And it impacts other issues — mental health and developmental issues,” Robinson said (1:49). “We’ve seen a significant uptick in mental health and emotional and developmental issues in the last several years, especially coming out of COVID and even really pre-COVID in the schools, and the schools having to deal with those issues.”

Students are also carrying the weight of negative home life factors into schools, including substance abuse and fiscal issues. Social media is largely to blame as well, says Robinson.

“Social media has certain positive impacts in society, but the negative impacts for kids that are constantly on social media and being bombarded with the TikTok challenges and bullying on social media and Instagram. They’re trying to outdo one another through these different crazy contests and different things that are going on, or the videos that are made and the next person wants to have their 15 minutes of fame,” he said. “Maybe it’s a violent incident, maybe it’s not. But again, the impact of social media on the kids and wanting to be influencers, there’s a positive/negative impact, and obviously the social stressors associated with all that.”

Arguably most detrimental is the lack of positive relationships and connections within a community, something research continuously shows can increase someone’s propensity for violence.

“We like to say a habit is established in 30 days and then it’s really pinned down after 60 and becomes part of your life after 90. Well, for 18 months to two years, people were locked in their homes and relatively antisocial by comparison to their normal pattern,” Cerny said. “This invites antisocial behavior, and as people returned to school, we saw the uptick in fights, bullying, and other kinds of events.”

That is why having processes in place to recognize “red flag” behaviors is essential to violence mitigation. To recognize those red flags, Robinson says, schools must establish a behavioral threat assessment team and a bystander reporting system.

“People report it and [the team] gets that intervention going to get me off that highway to violence,” he said. “I like to use the analogy that I’m on that highway to violence but there’s plenty of off-ramps and exits to get me off that path to targeted violence. Maybe I just need some counseling to help deal with stressors.”

School Behavioral Threat Assessment (SBTA) Solution from Secure Passage

Although a behavioral threat assessment team and bystander reporting system are crucial, how can schools, many of which have limited resources — particularly from a personnel standpoint — be expected to effectively organize, assess, and mediate behavioral threats when the sheer volume is nearly impossible to manage?

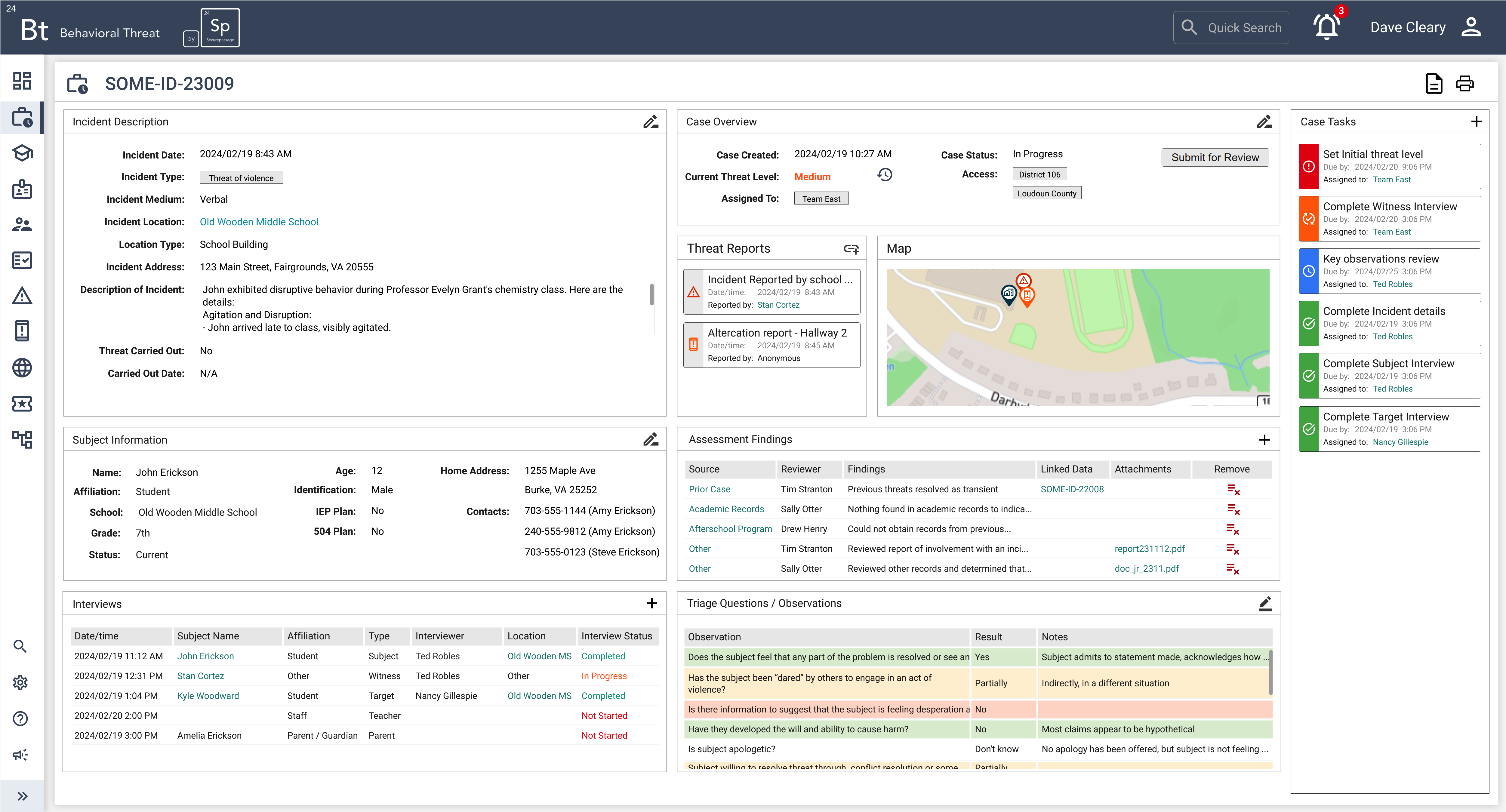

With the core mission of identifying, organizing, and prioritizing key digital and physical data, after more than three decades in the security space, Secure Passage developed its own School Behavioral Threat Assessment (SBTA) application for a school district in Northern Virginia in 2018 (13:28). The system uses various frameworks but leans toward the National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) model used by the Secret Service as well as the model used by Virginia’s criminal justice department. However, the solution is customizable to a district or state’s specific requirements.

“If they don’t currently have a framework in place that is authored or orchestrated by a state or by a district, we come with those frameworks, but beyond that, we are able to bring in the assessment pieces that might be bespoke within a district or a state,” Cerny described. “If there are requirements that need to be managed from that behavioral perspective — and oftentimes, it flows over into the physical security piece and it flows over into other elements of the educational ecosystem — we’re able to capture those kinds of assessment pieces that might be driven by the district or the state as well.”

The system helps identify and manage behavioral threats and houses them in a secure repository that gives staff and administrators the ability to see open and closed cases. It then allows school leaders to determine a response or intervention, if necessary, implement the chosen response, and then analyze how the case is progressing.

Behavioral Threat Assessment: Turning Students Around, Not Turning Them In

While protecting students from violence is crucial, mission-critical to Secure Passage is getting struggling students the help they need.

“Behavioral threat isn’t about turning people in. It’s about understanding the problems and turning them around. That’s the approach we certainly take,” said Cerny. “Even for busy professionals who’ve done this a million times, it’s important to follow the steps, kind of like a pilot in a cockpit. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve taken off and landed successfully. Hopefully, your ratio is exactly one-to-one, but then in addition, you have a pre-flight checklist that you go over. It doesn’t matter how many hours you have under your belt — this helps professionals analyze case records and then submit those reports to stakeholders as necessary so that information’s being shared with the appropriate parties at the appropriate time to get in front of something that could potentially trend toward violence.”

Although behavioral threat assessments can mitigate violence, they can also mitigate bullying and suicide (37:11). In 2022, Michigan’s OK2SAY tip line saw a 19% increase in tips compared to the year before. While instances or threats of school violence made the top five tip categories, the categories with the most tips were bullying and suicide threats. In Pennsylvania, more than 90% of tips submitted in the Safe2Say Something app in 2019 pertained to mental health issues, specifically suicides.

“Behavioral threat also helps with the potential turnaround of suicidal ideation and other kinds of things that we face in education,” said Cerny. “It has multiple needs to support the mental wellness of our people that we have within our ecosystem.”

As our country continues to face a teacher shortage and mental health concerns persist, technology must be used as a force multiplier — not a replacement — in improving campus culture and student safety.

“The more you can have a human-led, machine-driven solution, the better you’re going to be. And I say human-led because humans are always part of the process, you can’t automate everything,” Cerny said. “But automating multiple indicators of potential threat, bringing those together so an administrator, an analyst, a school resource officer, can immediately access that different information that’s been collated and presented within the Secure Passage platform, for example, is a huge advantage.”

Learn more about Secure Passage’s Student Behavioral Threat Assessment solution here.

What’s the Future of School Safety, Student Wellness?

While the school safety landscape may seem bleak, Robinson and Cerny, who perhaps many would assume are pessimists given their daily insight into school violence, both see hope on the horizon for school safety and student wellness (25:07).

“Five minutes before we joined this video recording, I was on with the governor’s office, and they were talking about within their state, the ability or the need to bring together the insights from their department of education, a university-based school safety center, the governor’s office and emergency management, et cetera — tying all of this together such that they can get to a crawl, walk, and then run posture with their security within the state for their schools,” Cerny said. “The positive that I see right now is longitudinally in education, we’ve had groups of schools, administrators, et cetera, trying to do the very best that they can with the resources that they’ve got to enhance the security of their school for their students, faculty, staff, and visitors. But now there are formal programs that are bringing together physical threat assessments, potentially behavioral threat assessments, other kinds of assessments where this is being addressed in a more formal way, but in a stair-step way that the posture is always getting better and better from a security perspective.”

Here are some additional topics discussed in the interview:

- A scenario that highlights the importance of identifying concerning or prohibitive behaviors and initiating the intervention process (4:44)

- Three ways schools can mitigate threats of harm (8:33)

- Common errors schools make regarding behavioral threat assessments (11:49)

- What makes Secure Passage’s SBTA unique (20:13)

- Hopeful thoughts for the future of school safety and student wellness (25:08)

- How schools can access fiscal and human resources to improve behavioral threat assessment capabilities (31:32)

The full interview transcript is below and includes subhead descriptions to help break up the discussion into easily digestible parts.

Watch the full interview here or listen on the go on Apple or Spotify.

How School Threats Have Evolved

Amy Rock (1:31): Today we are going to discuss the importance of school behavioral threat assessments, and we’ll kick off the discussion with Lew. Now, in your long career, you’ve specialized in behavioral threats. How have you seen the school threat landscape change over the years of that work?

Lew Robinson (1:48): Well, Amy, I would say thanks for having the interview today and meeting with Kirk and I to talk about this very important topic. The landscape has changed, in my opinion as a reflection of society today. Society has changed and the different stressors and factors that we see impacting both our school students and adults in society, that carries over into the school violence as well. So we look at all the factors similar. It could be trust and respect. We’ve really lost trust and respect in each other, trust and respect in our institutions, whether it be governmental schools and so forth. And it impacts other issues — mental health and developmental issues. We’ve seen a significant uptick in mental health and emotional and developmental issues in the last several years, especially coming out of COVID and even really pre-COVID in the schools, and the schools having to deal with those issues.

And again, another reflection of society as a whole, negative home life factors. These things that impact the home life come to school. So whether it’s a substance abuse in the home, mental health issues in the home, fiscal issues in the home, all those stressors impact the students and they bring that within the school. Social media — what can I say? Social media has certain positive impacts in society, but the negative impacts for kids that are constantly on social media and being bombarded with the TikTok challenges and bullying on social media and Instagram, trying to outdo one another and these different crazy contests and different things that are going on, or the videos that are made and the next person wants to have their 15 minutes of fame. Maybe it’s a violent incident, maybe it’s not. But again, the impact of social media on the kids and wanting to be influencers, there’s a positive/negative impact of that, and obviously the social stressors associated with all that.

Going back to that trust and respect, if I don’t have a positive relationship in the home with my family, positive relationship in the community with my peers, positive after-school events. I’m not involved in band. I’m not involved in my church youth group, I’m not involved in a sporting team, I’m not involved in scouting — something that gives me a positive outlet. All those stressors are coming together and just that lack of positive relationships tied in with all of these other things, that stress comes together and the kids are at school eight hours out of the day, and where’s a lot of that violence going to happen? It’s going to be on the school bus, it’s going to be at school on the way home at the bus stops. That’s where you’re going to see the violence. It comes to school.

Scenario: Student Becomes Irritable, Grades Deteriorate

Amy Rock (4:44): And now, I also wanted to ask, using your background as a roadmap, can you share a scenario that highlights the importance of identifying concerning or prohibitive behaviors and initiating the intervention process?

Lew Robinson (4:58): Sure. And I give this scenario quite a bit, and if I do presentations on behavioral threat assessment in schools, I’ve used this through the years, and I think it highlights the importance of identifying warning signs, your red flags in that intervention. I like to use scenario, I’m a freshman in high school, I’m involved in scouting. I’m involved in my church youth group. I have a lot of friends, positive relationships with friends, doing really well in school, the first half of school. Second half of school, my behavior changes, something’s going on. I’m irritable. I’m not participating in class. I’m lashing out at others and scouting, maybe I’m not attending the meetings, not attending youth group. And there’s some behavioral flags that are raised that my friends and my teachers notice.

As the school year progresses, my grades are going down, but now it’s March. I’m a kid that loves to play baseball, and I try out for the baseball team, and I get cut from the baseball team. My focus now goes to my gym teacher who is the baseball coach. All the sources of my problems are not the baseball coach because he cut me. I start fixating on the baseball team, baseball coach, I’m going to get that guy for cutting me. But what they don’t know what the background is, we didn’t pick up on those red flags is I’m having some of those stressors at home that I mentioned. My parents are getting divorced. There’s physical issues in the family, and it’s impacting me, and I don’t know how to handle that stress. So now I fix it on the baseball coach because if that baseball coach hadn’t to cut me and I was able to make that baseball team, well, that would’ve saved my parents’ marriage. They could come watch me play baseball and cheer me on and enjoy and get back together as a family and have some good times together. But he hasn’t done that, he cut me. Now I’m focused on him.

So now I’m drawing schematics, little doodles on the side of the paper with guns or explosives or different things, and I’m posting things on social media. I’m showing an interest in violent events, things that are just red flags and things that if you use that community systems approach — I talked about scouting in school and the church youth group — there’s things that are there in my behavior that have changed, but nobody says anything. Nobody picked up on that. But if they had picked up that I’m doing this, and the peers in my class are seeing my notebook, and again, my grades are going down, nobody put together what is going on? What’s happening in his life that’s caused this? A good kid, and now something’s happened. Okay.

Some of those red flags, having a behavioral threat assessment team management team in place in the school picks up on those red flags, having a bystander reporting system in place picks up on those red flags. People report it, and we get that intervention going to get me off of that pathway, that highway to violence. I like to use another analogy that I’m on that highway to violence, but there’s plenty of off ramps, exits, to get me off of that path to targeted violence. So I’m not attacking the school, I’m not going after my gym teacher, I’m not going after the other baseball players on the team. You’re able to get me off of that highway of violence, use that exit ramp, get me the help that I need, maybe just some counseling just to help deal with that stressor of my parents being divorced and going through that separation and divorce. Again, coming back to that mental health, student wellness, and just a good quality behavioral threat assessment would’ve identified and picked up on those things and got me the help that I needed.

Processes, Systems for Mitigating Potential Threats

Amy Rock (8:33): I know we’re here to talk about behavioral threat assessments, but there isn’t just one thing that can be implemented to prevent and mitigate violence. So what are some additional processes, systems or programs schools should have in place to mitigate potential threats?

Lew Robinson (8:46): The best practice certainly be to establish a behavioral threat assessment management team that handles a school district, or maybe they’re going to be specific to the school, maybe an overall school district team and then a team at each school. But to establish that behavioral threat assessment management team and develop policies and procedures, and someone’s going to lead that team and training and everything. Make that a quality robust team.

And again, with that bystander reporting, having reporting system in place. Some states have a state level mandate, others do not. It could be school districts choose what system they want to use and so forth. But again, having that so that I can make that anonymous report or a confidential report and get that process going. We talked to intervention in the last question to get that going.

The other thing is what I say in the beginning, trust and respect. Schools have to build a culture of trust and respect in their schools so that kids feel comfortable coming to teachers, talking to the bus driver, talking to the janitor, the maintenance staff, maybe their guidance counselors, having some trusted relationship within the school to know that if I come forward and say something about a peer that I’m concerned about, that they’re going to take it seriously and they’re going to act upon it. And if they act upon it, I don’t want to come forward if they’re going to say, “Lew Robinson just said that he saw Joe Smith doing something.” We keep it confidential and you continue to do that and build that trust so I’m not building up a fear to report. Again, make that positive influence on these kids so that they are willing to come forward because school safety, really, it’s everybody in that community — the school, the students, the staff, administrators, so forth, and all the community stakeholders involved in school safety. It takes that whole group to keep the school safe. So in a nutshell, it’ll be those three things that I just mentioned: establish a team, have a reporting system, and truly a strong, robust culture that builds a strong relationship with the kids and trust in reporting.

It could be the invisible ones. You could say who thinks of the maintenance staff at the school? They’re going to see and hear a lot of things from kids. They don’t think that they’re listening or, “Oh, it’s just Mr. Jones, the maintenance engineer.” Or school bus drivers — all the stuff that goes on in a school bus – good and bad — that school bus driver knows all that stuff. They hear these things. It’s also getting those folks could be a part of your behavioral threat assessment management team and that multidisciplinary team. Again, taking a look at what you need, making a good sound team put together, made up of those individuals.

Common Errors in School Behavioral Threat Assessments

Amy Rock (11:46): As many eyes and ears as possible, for sure. And now you mentioned behavioral threat assess teams, and there obviously are schools that have these teams and certain procedures in place but might not be utilizing them properly. The biggest, most recent example we can think of is Oxford High School where they had a process but they didn’t follow it, and there was also a lot of confusion as to who would spearhead the threat assessment team.

Are there any common errors you’ve seen being made regarding behavioral threat assessments, whether that be through policy, execution, recovery, et cetera?

Lew Robinson (12:20): You have to train, I’ll use the analogy again. I’m a baseball guy, played baseball in college, so everything I do comes back to baseball where it’s a scenario analogy I’m using. So in this case, the catcher knows what the first baseman’s going to do in this play. Same with the second baseman, shortstop, third base, pitcher. We all know what we’re supposed to do. I know my individual role, I know what your role is. It’s the same with this multidisciplinary threat assessment team. We have to know what each other’s role is, understand our piece of it, but understand also what my partners, my teammates are doing. So that’s why it’s very important as a training piece. They should meet monthly, go over things. If there’s no cases reviewed, they could use scenarios like we used earlier and walk through that as a training exercise just so that they’re good. Understand what each other’s doing in that process so that they do have a quality team in place that can address these threats. And again, that early intervention, get me off of that path of violence.

Secure Passage’s School Behavioral Threat Assessment (SBTA)

Amy Rock (13:18): And now that brings us to potential solutions that are available to aid schools in addressing behavioral threats, including those offered by Secure Passage. So I’ll switch over to you, Kirk. Can you just give a brief history and overview of the company and what you guys do?

Kirk Cerny (13:33): Yep. Thank you very much, and it’s a pleasure to be with you today. First of all, we’re not new to the business of security. Our organizations span back 30 years in digital security as well as physical security. We got our start in physical security as it relates to behavior in the late nineties, early two thousands, working on projects that would assist our customers in the federal government to understand who might be likely to attack or be a threat to that agency, that organization or the people, places and things that they have. And so we began that journey as insider threat specialists, which all ties into behavior and how behavior is addressed from a security perspective. We embody the principle at Secure Passage that it’s all security to us, meaning that there’s digital security, there’s physical security. All of it needs to be converged or blended in order to give the best picture possible for understanding a threat and mostly for safeguarding or raising the security posture of your organization.

Our core mission is really designed to be meticulous about the identification, organization, and prioritization of the key digital and physical data that an organization needs to understand, visualize and be safe about. When it comes to behavioral threat, certainly having a platform in place to be able to capture the data, manage the cases, understand and inform all stakeholders, is something that we are passionate about. And we’ve built that foundation of a platform on the decades of experience that we have in digital security and physical security, but also law enforcement, behavioral science, critical infrastructure, and education.

Personally, I’ve got 25 years of experience in the education space, so understanding how all of those pieces come together in order to provide an ecosystem that is first of all, understanding the threat that’s in their environment, as well as then, the ability to, as Lew mentioned, mitigate on a pathway to violence. Somewhere along the way, stepping in front of the individual and turning them around. By the way, behavioral threat isn’t about turning people in. It’s about understanding the problem and turning them around. That’s the approach certainly that we take.

From a platform perspective for behavioral threat, more than a decade ago, we’re not new to this, we started looking for a solution and then building ultimately a solution, managing campus risk: in-depth discussions with district leaders, school administrators, security professionals, district police chiefs, certainly counselors, school psychologists, teachers and operations staff. We built a platform to support education and the various needs that security remits have, but also something that takes the input of all of those different parties and blends them together. So as Lew was mentioning earlier, having a behavioral threat management team really comes from the foundation of work that we’ve put into our platform.

We developed at Secure Passage, the first behavioral threat assessment application of our own in 2018, and it was for a large school district in Northern Virginia where they were using the application really to identify, assess, manage behavioral threats as they exist of all types, and then put it into a secure repository of data that is supporting records, giving staff and administrators the ability to see open and closed cases, and certainly in a role-based access controlled, not available to the internet type of solution that is a security-first posture for behavioral threat assessment.

We use a variety of frameworks, but we lean toward the NTAC model with the National Threat Assessment Center from the Secret Service as well as the Virginia model, which is the Virginia accepted model from their criminal justice department. The model is not as important at a baseline for what a district is using, but moreover, to understand the way that they want to manage a behavioral threat program. But if they don’t currently have a framework in place that is authored and orchestrated by a state or by a district, we come with those frameworks, particularly NTAC and the Virginia model, and then beyond that, we are able to also bring in the assessment pieces that might be bespoke within a district or a state. If there are requirements that need to be managed from that behavioral perspective, and oftentimes, Lew, as you know, it flows over into the physical security piece and it flows over into other elements of the educational ecosystem, we’re able to capture those kinds of assessment pieces that might be driven by the district or the state as well.

So very comprehensive, but certainly a way to surgically take the evidence that might be growing for behavioral threat around an identity — one student or one staff member or even third parties — we need to understand the threat that they might bring to the school as well. All of that can be captured within the Secure Passage platform for behavioral threat assessment, and then give you the insight that you need as an organization to make good and solid decisions. Again, in this case, to get in front of that potential problem, understand it from a clinical perspective, but also from just a human and behavioral perspective to turn that individual around it and have positive outcomes with a behavioral threat management program.

What Makes Secure Passage’s SBTA Solution Unique?

Amy Rock (20:13): Now, Secure Passage, as you said, has been in the industry for decades. Your school behavioral threat assessment solution, what do you think makes it unique from similar solutions?

Kirk Cerny (20:25): Well, number one, the ability to customize the threat assessment based upon the needs or the requirements of the jurisdiction. But then also the underpinnings of having professionals like Lew, for example, that have utilized the frameworks in a variety of settings, including educational settings, K-12, higher education, et cetera, and have conclusively mitigated threats based upon that framework.

What we do find is that there’s a national conversation now about mental wellness and education. This is something that certainly professionals have talked about for a very long time. You go to the website of the National School Psychologists Association. They have deep and wide material on behavioral threat, but it is just now really entering the public discourse. We have presidential candidates in this election cycle who are actually talking about mental wellness as it relates to education. This is a piece of the security puzzle that we know has been very important for a very long time, but districts and states are taking it more seriously now because of the uptick in, as Lew mentioned, kind of the antisocial behavior that has come from the conditions in which we live today, whether it’s a rather chaotic society or an antisocial society coming out of lockdowns.

We like to say a habit is established in 30 days and then it’s really pinned down after 60 and it becomes part of your life after 90. Well, for 18 months to two years, people were locked in their homes and relatively antisocial by comparison to their normal pattern. This invites antisocial behavior, and as people returned to school, we saw the uptick in fights, bullying, and other kinds of events. We also have seen an uptick in school-related violence as it relates to sharp objects and guns.

The other thing that we find with practitioners that we’re working with in the education space and corporate space as well, interestingly, this problem is societal. It’s not just K-12 or on campus or in hospitals, et cetera, but it is a nationwide a societal issue. The practitioners, because they’re busy people, and oftentimes there might be multiple cases that they’re looking into, they need an ability to walk through step by step some of these guidelines. The NTAC guideline, for example, Lew, I think that’s somewhere in the neighborhood of 60 pages. The Virginia guidelines are upwards of 90 or a hundred pages of material to ingest and then operationalize. We help users by allowing them, first of all, to have a place to open a case to review and validate incoming reports and that sort of thing, but then have a place, a source of truth for that information to reside that allows them then to determine a response or intervention if necessary, implement the chosen response, and then understand how the case is progressing. And if this is something that is substantive and we really need to intervene, or if it’s something that’s more transient, someone in a hallway saying, “I don’t like you, and next time I see you, I’m going to punch you in the face.” Well, that kind of thing is very transient versus something that’s substantive like, “I am going to come to school, not only punch him in the face, but I’m going to stab him.” So those kinds of things are taken into account as well so that the practitioners can analyze those records, make sure that the processes for intervention are well followed.

Even for busy professionals who’ve done this a million times, it’s important to follow the steps, kind of like a pilot in a cockpit. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve taken off and landed successfully. Hopefully your ratio is exactly one-to-one, but then in addition, you have a pre-flight checklist that you go over. It doesn’t matter how many hours you have under your belt — this helps professionals analyze case records and then submit those reports to stakeholders as necessary so that information’s being shared to the appropriate parties at the appropriate time to get in front of something that could potentially trend toward violence.

Is There Hope for School Safety, Student Wellness?

Amy Rock (25:07): Yeah, absolutely. Now, I wanted to ask a few questions that Lew, Kirk, either of you or both of you are invited to answer. A lot of topics we cover on Campus Safety can be heavy and disheartening, and I imagine you guys feel that sometimes. And I would like to end our chat today with some hopeful thoughts or takeaways for the future of student and school safety. Do either of you see hope on the horizon for how schools are addressing increased violence?

Kirk Cerny (25:36): And my response, Amy, is five minutes before we joined this video recording, I was on with the governor’s office, and they were talking about within their state, the ability or the need to bring together the insights from their department of education, a university-based school safety center, the governor’s office and emergency management, et cetera, tying all of this together such that they can get to a crawl, walk, and then run posture with their security within the state for their schools.

So the positive that I see right now is longitudinally in education, we’ve had groups of schools, administrators, et cetera, trying to do the very best that they can with the resources that they’ve got to enhance the security of their school for their students, faculty, staff, and visitors. But then now there are formal programs that are bringing together physical threat assessments, potentially behavioral threat assessments, other kinds of assessments where this is being addressed in a more, as I mentioned, formal way, but in a stair step way that the posture is always getting better and better from a security perspective.

This is something that in cybersecurity for the past 20 years, companies, organizations, governments, everybody’s being hacked all the time. We put controls or layered security if you will, in place to enhance that step by step. But on the behavioral side, as I mentioned earlier, we’re just now getting around to, at least as a national effort or a national conversation, to address it. That being said, there are some school districts in America that have been conducting behavioral threat assessments and have had very successful behavioral threat management teams for a very long time, for decades in some cases. So good progress has been made, but certainly those that have programs in place, they are being asked by their colleagues in school safety, “How did you do it? How do you actually operationalize it once you understand a framework you want to follow?” And moreover, how do we make this, from a state perspective, available to the biggest city that’s in our jurisdiction or in our footprint all the way to the rural school that may not have similar issues day to day, but do have some commonalities and need to be supported. So it is one of those IT situations where from a positive perspective, we’re making progress against behavioral threat. It is expanding rapidly. People need to know what to do, and we can certainly help them with that flow, with that process based upon our decades of experience in that behavioral space.

The biggest challenge is just the volume of events and data that is coming across. You’re not only talking about multiple cases that you might be tracking, but each one of those cases has multiple sets of data that allow you to glean deeper insights on the trends that are happening with that individual. A shift in behavioral pattern, for example. This is something that practitioners have a hard time getting ahead of and having a formal program in place, number one, with a behavioral threat management team, as Lew mentioned, as well as then a tool that resides as your source of truth gives an organization a significant advantage in staying in front of multiple cases and multiple threats coming potentially from multiple different sources at any given time.

Amy Rock (29:42): I spoke to a Campus Safety reader who’s a practitioner. He was a security director at a K-12 school a couple of years ago, and he was saying how he literally gets the anonymous tip sent to his phone and a person just can’t be expected [to handle that]. He works 24/7, basically, because his phone rings that a kid submitted an anonymous report at 3:00 AM because someone was scrolling on social media and saw it. And that’s where technology can help those practitioners, who are so already overwhelmed, not have to do that 24-hour-a-day job.

Kirk Cerny (30:22): Exactly. The more you can have a human-led, machine-driven solution, the better you’re going to be. And I say human-led because humans are always part of the process, you can’t automate everything. But automating multiple indicators of potential threat, bringing those together so an administrator, an analyst, a school resource officer, can immediately access the different information that’s been collated and presented within the Secure Passage platform, for example, is a huge advantage. Leveraging technology to bring together that information more quickly because they say that seconds count, right? So it’s important even in your day-to-day ecosystem to be drawing together the potential indicators of threat as quickly as you can to reduce the time to detection of that threat to reduce the time to mitigation and response of that threat.

Available Resources for Behavioral Threat Assessment Improvement

Amy Rock (31:32): You had also mentioned in your answer, schools working with resources that they have, which brings me to my next question. What advice do you guys have for schools or districts that might be struggling with their threat assessments due to a lack of resources? We know there’s not enough mental health care providers, there’s not enough social workers in schools. What advice do you have for schools struggling a little bit?

Kirk Cerny (31:55): I’ll take the first pass. I actually served on a committee in a state where we made grants for school safety from the Department of Homeland Security. And in as much we saw availability of millions of dollars each year out of the state that schools could apply for in a grant allocation. This kind of solution would meet the requirements of a security product or a security enhancement to which those kinds of funds could be made available. The states have been, as you read in Campus Safety magazine, making significant investments in school safety. So the state itself can be a resource.

There’s potentially a question of haves and have nots. If your district has a grant writer, oftentimes you can access more funds, both state and federal funds for school safety. It’s important for the administrators to look for those resources that are available from the state. Those may come from the Department of Education, from Emergency Management or Department of Homeland Security within the state. They can also certainly come from other kinds of organizations or groups like the State Association of School Boards. School board members, as well as superintendents as well as you go along the chain of administration in schools, they are very focused on behavioral threat at the moment, mental wellness of the students. So this is an important thing to understand that those groups may be also funding or seeking sources of funding for those types of behavioral programs. Lew, did I steal your thunder, sir?

Lew Robinson (33:49): Well, maybe just a wee bit, but I’ll pimoggyback on what you said because you focused on the fiscal resources and how to do that. So I’ll look at the human resources for a district. As Kirk mentioned, a smaller rural district, maybe they’re going to partner up with their neighboring school district and they’re going to have a joint behavioral threat assessment team and pull their resources together to cover both. Maybe they’re going to leverage human resources from the county level or the state level mental health professionals, taking advantage of the tools that are already out there, the organizations that are already out there to be a part of your team that helps you accomplish that mission. And like Kirk said, there’s the grant writing process and the grants that are out there, but there is also thinking outside the box, if you will, bringing in those human resources from others.

You have to be efficient with your resources, and nobody has unlimited resources, both human resources and fiscal, and how can we be affected by mutually helping each other address this situation in our school districts, in our communities? Maybe local law enforcement has developed a threat assessment program and looking at these things in their community, leveraging the county mental health professionals, other law enforcement agencies in the area, coming together and making a behavioral threat assessment team for the county or the city. Well, maybe the school district becomes a part of that team and that team looks at issues within the school district.

How to Mitigate School Violence Today

Amy Rock (35:24): And one final question to close out our discussion today — if listeners could go do one thing after listening to this podcast that would make a difference or help their school or district better handle or address behavioral threat assessments, what would that be?

Lew Robinson (35:40): I’ll bat lead off on this one, Kirk. I would say it ties back to the common theme through what we’ve talked about here. If you’ve not established a behavioral threat assessment management team, please do so as soon as you can. As a part of that, as we mentioned through your developing policies and procedures, how your team’s going to operate that multidisciplinary threat assessment team, identifying a leader, identifying a training process for the people that are on your team to work together. And then identifying a tool like Secure Passage provides that’s available to help that team be successful in their mission. Again, taking a look at everything and putting it together, and this tool helps them accomplish that.

Kirk Cerny (36:26): That’s a beautiful answer. And being formal and being deliberate about the process is key. And certainly as we visit with superintendents and school board members and even governors, they’re tuned in now, I believe, to solidifying a formal process. And that is necessary in order for all of this to work. So ties in very much with what Lew said, but those are the voices from the field today who are saying, “Yep, it’s time.” And indeed as a national conversation, I believe we’re there. It’s time. And as it relates to those of us that have spent time in education and working with our students, faculty, staff, and our third parties that visit our schools, this is one of the greatest challenges that we know we’ve faced throughout our history. Behavioral threat also helps with the potential turnaround of suicidal ideation and other kinds of things that we face in education. It has multiple needs to support the mental wellness of our people that we have within our ecosystem. So thank you very much for the opportunity to talk about it today. And indeed a formal program would be the first best step.