The below article, originally published on April 18, 2023, was last updated on March 4, 2025, to include findings from a new study.

A survey released last year by the National Education Association (NEA) found 55% of educators want to leave teaching earlier than they originally planned. The main reason? Burnout from massive labor shortages.

About one in six teachers expressed they would likely leave their job pre-pandemic. This increased to one in four by the 2020-21 school year. In 2021 and 2022, teachers were twice as likely to report experiencing frequent job-related stress and difficulty coping with their job-related stress than the general population of working adults, according to the 2023 State of the American Teacher survey, released by RAND in June.

At one elementary school within the Fort Worth Independent School District, there was a whopping 88% teacher turnover rate for the 2022-23 school year. The year prior, there was a 42% turnover rate.

“More than half of our teachers are reporting frequent job-related stress and burnout, and that number is even higher for our Black educators and our female educators,” said NEA President Becky Pringle. “Teacher well-being continues to remain worse than that of other working adults, and this crisis is hurting our students and our communities.”

In March 2024, Education Resources Strategy (ERS), a national nonprofit that partners with school system leaders, released an analysis of teacher turnover trends from 2021 to 2023. Using data from nine large, unnamed urban and suburban school districts, 23% of teachers left their school or teaching role during the 2022-23 school year. While it is higher than pre-pandemic turnover in the sample, which was around 18% during the 2019-20 school year, it is lower than the 2021-2022 school year’s peak of 26%, Education Week reports.

Most impacted by the shortage are higher-poverty schools. The ERS analysis determined schools serving the greatest proportion of students from low-income families lost 29% of their teachers between Oct. 2022 and Oct. 2023. Schools with the lowest concentration of poverty lost 19%. When teachers change schools within their district, they are much more likely to move to a more affluent school.

K-12 Teachers Have Highest Burnout Rate of All Industries

A 2022 survey from Gallup found K-12 school employees have the highest burnout rate of all industries nationally with 44% reporting they “always” or “very often” feel burned out at work. Female K-12 employees are also more likely to report feeling burned out. College and university workers have the next-highest burnout rate at 35%. Here are some additional findings on college faculty burnout. (See charts from the Gallup study that compare burnout rates by industry and gender.)

More recently, a 2024 survey from Study.com found 36% of middle and high school teachers said burnout and mental health issues were among their top challenges going into 2025, driven primarily by overwhelming workload, administrative tasks, and classroom management. More specifically, 32% cited classroom behavior management as a top issue for this coming year and 38% said reducing class sizes would make the most significant positive impact in teaching experience in 2025.

While teacher shortages predate the pandemic, particularly for substitute teachers and in hard-to-staff subjects such as math, science, special education, and bilingual education, these shortages have grown in the past three years and expanded to encompass other positions such as bus drivers, school nurses, and food service workers, Campus Safety previously reported.

The pandemic kicked off the largest drop in education employment ever. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of people employed in public schools — not just teachers — dropped from almost 8.1 million in March 2020 to 7.3 million in May. Employment has grown back to 7.7 million since then, but schools are still short nearly 360,000 positions, according to The Hechinger Report.

There are currently 567,000 fewer educators in America’s public schools today than there were before the pandemic. Nationally, the ratio of hires to job openings in the education sector has reached new lows as the 2021-22 school year started. It currently stands at 0.57 hires for every open position, according to BLS’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS).

While Teacher Demand Is High, Wages Remain the Same

Perhaps also contributing to the educator shortage is the addition of specialized positions and/or job requirements created following the pandemic. According to data released in Feb. 2024 by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 39% of schools now have an Indoor Air Quality coordinator on campus. This position is responsible for monitoring air quality conditions at the school and reporting air quality issues and complaints.

Furthermore, 42% of public schools with one or more instructional coaches working at their school (i.e. literacy coaches and math coaches) reported they have added more instructional coach positions since the 2019-2020 school year. Another 42% have a parent/family engagement specialist or outreach worker at their school. Among all public schools, 17% reported adding this type of position since the 2019-2020 school year.

Within the same NCES data set, nearly 80% of public schools said hiring general elementary and special education teachers for vacant spots remains a challenge. Two-thirds reported their biggest challenge in hiring teachers was a lack of qualified candidates while 70% said there are too few candidates applying for open teaching positions.

According to a March 2024 analysis by the ADP Research Institute, the imbalance between high demand and short supply should have led to higher wages but it hasn’t. The analysis determined teacher salaries are growing more slowly than average wages for all employees. The national average teacher salary is around $68,000 which is 8% less than the average U.S. worker’s salary. The pay gap is greater among teachers 30 and younger, the study found.

Research from study.com, released in Nov. 2024, found that among teachers considering leaving their jobs within the next five years, addressing the following support needs would make them reconsider:

- Improved salary and compensation (75%)

- Better work-life balance, such as more planning time, reduced workload (43%)

- Better support for managing student behavior and classroom challenges (34%)

Survey: Teachers Value School Support Staff More Than Pay

While low wages continue to factor into the teacher shortage, new findings suggest many teachers would trade an increase in salary for additional school support staff, such as special education co-teachers, paraprofessionals, school counselors, and nurses.

The survey, published Nov. 12, 2024, and conducted by Virginia Lovison, associate director at Deloitte Access Economics, and Cecilia Hyunjung Mo, associate professor of political science and public policy at University of California, Berkeley, suggests investing in specialized support roles may be as crucial as offering competitive pay.

“Our study reveals that teachers would rather trade pay raises for the assurance of support staff like full-time special education co-teachers, who help alleviate classroom burdens,” Lovison and Mo wrote. “It’s surprising just how much teachers value this kind of in-school support over additional income.”

The survey found teachers are willing to trade a 21% pay raise for a full-time special education co-teacher and 18% for a paraprofessional aide. The presence of a full-time school counselor is also worth $6,734 in trade-off value to teachers, more than double the cost per teacher of $2,475.

“These insights suggest that school and district leaders should prioritize the hiring and retention of support staff that make classroom jobs more attractive and should consider benefits beyond pay raises to attract and retain teachers,” the researchers wrote. “Union leaders and policymakers should consider broadening their efforts to enable teachers to work alongside more school counselors, nurses, and special-education specialists.”

Majority of Schools Have Special Education Teacher Vacancies

While most teachers value special education teachers over a pay raise, a National Center for Education Statistics report found 70% of schools had special education teacher vacancies in the 2023-24 school year. The Council for Exceptional Children and the Council of Administrators of Special Education also say about half of special education teachers leave the profession within the first five years of teaching.

During a Nov. 15 meeting with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, educators, researchers, advocates, parents, and attorneys said the shortage of special education teachers is hurting the academic growth and due process rights of students with disabilities, K-12 Dive reports.

Jessica Tang, president of the Massachusetts chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, said the shortage of special education teachers, as well as special education professionals and support staff such as speech language pathologists, behavior specialists, and paraprofessionals, means “students are not able to access critical services in a timely way, directly affecting their educational and social development.”

Twenty-two panelists spoke during the meeting, offering a wide variety of solutions such as raising teacher salaries, increasing class sizes, reducing compliance tasks, offering more school choice, and investing in teacher career pipelines. Several panelists recommended more funding under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act to support higher wages for special educators.

“We need to recognize that teaching is a profession and not just a job, and it should be created and treated with the respect and compensation that it deserves,” said Terita Gusby, CEO and founder of Education Prescriptions, a virtual tutoring company for students with disabilities.

The commission is studying the issue and plans to publish an Annual Statutory Enforcement Report on it in the second half of 2025. The findings and recommendations will be shared with the president and Congress.

Number of Employed Teachers by State

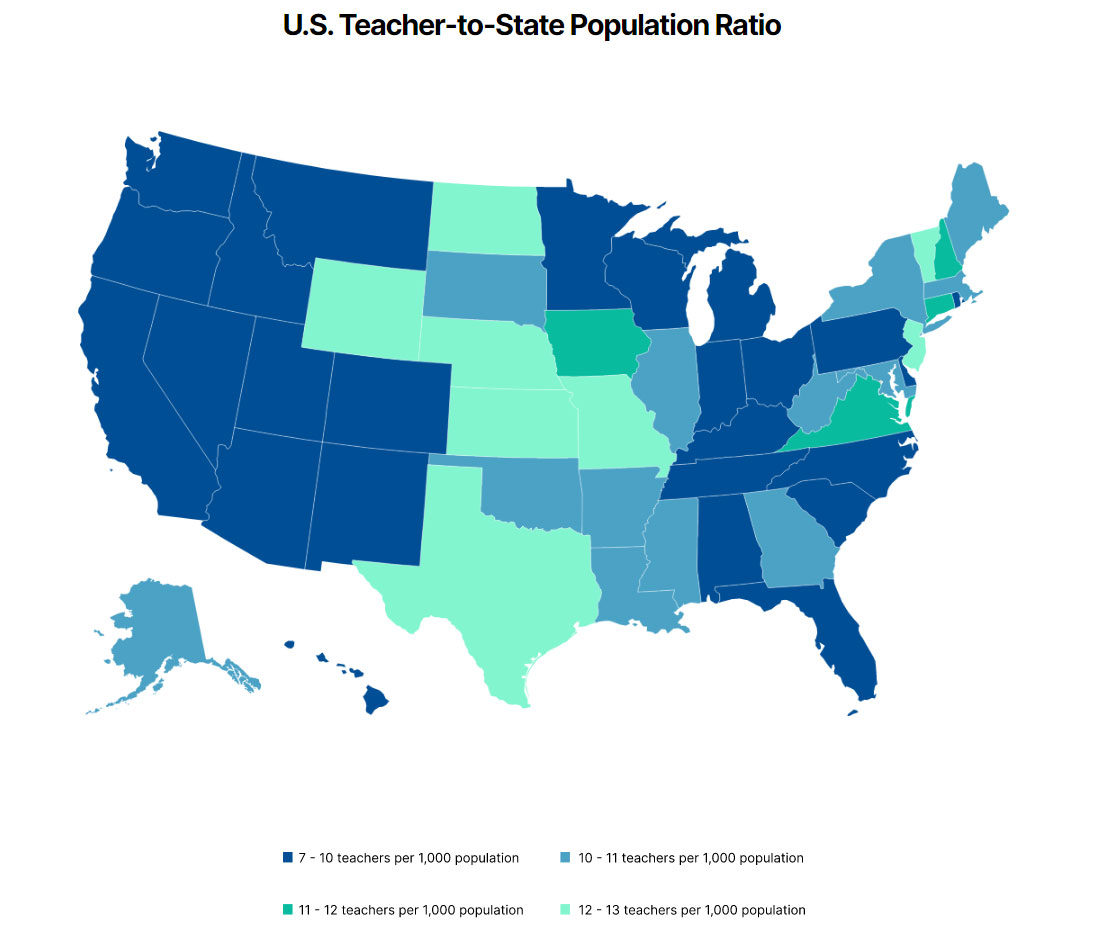

To see where each state stands regarding teacher staffing, Scholaroo, a scholarship search platform, compared the number of currently employed teachers in each state to the state population.

Please note these findings don’t take into account what percentage of each state’s population is school-aged or what the enrollment numbers are. For instance, only 18.8% of Vermont’s population is under the age of 18 while 29% of Utah’s population is under 18, according to PRB. Florida, which ranks the lowest in teacher-to-state population ratio, has the second-highest percentage of homeschooled children at 22.5%, says a study conducted by Q for Quinn.

The researchers created four categories. Here’s the breakdown and also the number of states that fall under each category:

- 7-10 teachers per 1,000 population: 25 states

- 10-11 teachers per 1,000 population: 13 states

- 11-12 teachers per 1,000 population: 4 states

- 12-13 teachers per 1,000 population: 8 states

Source: Scholaroo

Below are both the 10 best and the 10 worst states when it comes to teacher-to-state population ratio. The full list and a more detailed breakdown, including an interactive map, can be found here.

10 States with Highest Teacher-to-State Population Ratio

- North Dakota

- Nebraska

- Vermont

- New Jersey

- Wyoming

- Texas

- Missouri

- Kansas

- New Hampshire

- Iowa

Scholaroo also recently conducted another study on student safety, taking into consideration school security measures, bullying prevention programs, and other initiatives designed to ensure students feel safe at school. New Jersey, Vermont, and New Hampshire — all in the above list — ranked in the top 10.

10 States with Lowest Teacher-to-State Population Ratio

- Florida

- Oregon

- California

- Nevada

- Hawaii

- Michigan

- Washington

- Arizona

- Kentucky

- Tennessee

Nevada, California, and Arizona ranked in the bottom 10 states in Scholaroo’s student safety survey.

Teacher Shortages by State

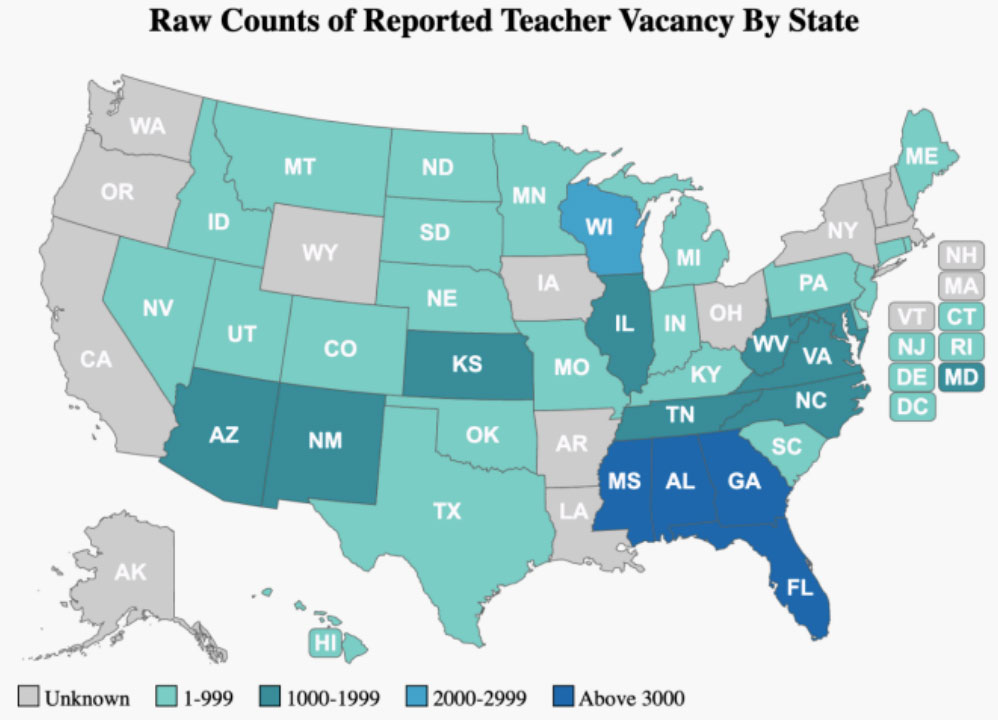

Perhaps a more accurate way to assess the current teacher shortage is by looking at teacher job vacancies by state. An Aug. 2022 study released by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University found there are at least 36,000 vacant full-time teaching positions in the United States with the number potentially as high as 52,800 (some states have not provided figures). The breakdown by state can be seen in the graphic below.

Source: Nguyen, Tuan D., Chanh B. Lam, and Paul Bruno. (2022). Is there a national teacher shortage? A systematic examination of reports of teacher shortages in the United States. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-631).

The highest number of open teaching positions are concentrated in the south and lower Atlantic where around 22,000 positions are vacant — almost three times higher than in the Midwest. Georgia had the highest number of vacancies (3,112) for the 2019-2020 school year. More recently, during the 2021-2022 school year, Florida had the most vacancies with 3,911 positions unfulfilled. That same school year, Mississippi and Alabama had over 3,000 vacancies. Sixteen states reported under 1,000 vacancies during the 2021-2022 school year. The states with the fewest vacant teacher positions were Utah (37), Missouri (38), and Nebraska (42).

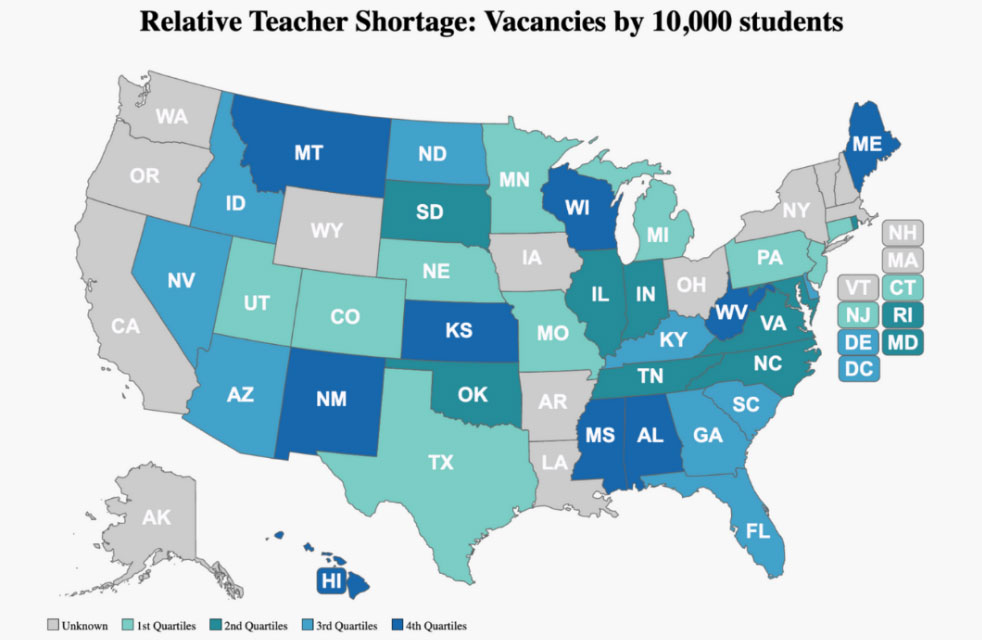

The researchers also broke down vacancies by 10,000 students, noting, “When student population is taken into consideration, the distribution changes substantially, and there is less of a geographical concentration of vacancy.” For instance, in the graphic below, there is no longer a cluster of high vacancy states in the southeast. However, Mississippi and Alabama are still among the states with the highest number of teachers needed for every 10,000 students.

Source: Nguyen, Tuan D., Chanh B. Lam, and Paul Bruno. (2022). Is there a national teacher shortage? A systematic examination of reports of teacher shortages in the United States. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-631).

Increased Mental Health Issues, School Violence Continue to Impact the Teacher Shortage

In addition to teachers, there are also significant shortages of mental health professionals in schools. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends at least one counselor for every 250 students. The national average is currently around 444 students per counselor. Compounding this shortage, child mental health concerns and school violence have skyrocketed since the pandemic.

A survey of 15,000 educators found a growing trend of students verbally and physically harassing teachers, as well as parents engaging in online harassment and unprovoked retaliatory behaviors against teachers. One-third of surveyed teachers reported experiencing at least one incident of verbal or threatening violence from students during the pandemic, and over 40% of school administrators reported verbal or threatening violence from parents. All respondents reported significant verbal or threatening victimization from students, parents, colleagues, or administrators.

As for physical violence, school staff (i.e., paraprofessionals, school counselors, instructional aides, and school resource officers) reported the highest rates with 22% reporting at least one incident of physical violence by a student during the pandemic. The RAND survey found 26% of teachers indicated they feared for their physical safety at school. Students misbehaving or having verbal altercations and fear of an active shooter were the top reasons teachers feared for their safety.

While many factors come into play regarding an increase in school violence, most who work in the education industry will agree that the ongoing staffing shortage is unequivocally one of those factors. It is a complete Catch-22 situation. With violence in schools on the rise, more teachers are leaving the profession and many who were once interested in becoming teachers have now changed their career paths due to safety concerns. Each issue fuels the other, and various entities are trying to come up with ways to combat the shortage.

Teachers Frustrated by Administrative Approaches to Education

Many who have a teacher or educator in their lives have likely heard about the hardships and qualms that often come with working in education. Students can be challenging, as can parents, and as a whole, society agrees that educators are underpaid for how important their job is. Some educators are also becoming increasingly frustrated with administrative approaches to education.

As one educator said in a recent blog post, “I wanted to teach; my administrators wanted to get the maximum number of students a diploma with the least amount of friction.”

In his post, Jeremy Noonan wrote that in 2007, he turned down a high-paying job in engineering to become a public school science teacher.

“I believed that making a difference in the lives of kids and maintaining the tradition of Western civilization would give my life meaning and value that money couldn’t measure. But I soon discovered that my ideals were often at odds with the school administration’s priorities,” he wrote. “The conflict between the bureaucratic, managerial priorities of school administrators and the moral ideals of teachers has characterized my seventeen-year teaching career.”

While frustrated with administrators, Noonan notes it’s much bigger than who is running a school or a district.

“The public school accountability system, by relying solely on quantitative metrics like graduation rates to gauge educational quality and to evaluate administrators, frustrates teachers’ ability to truly teach and care for their students and look out for their long-term well-being,” he continued. “While graduation rates have climbed steadily over the past twenty years, indicators of actual student achievement have stagnated or declined, leaving only a minority of graduates prepared for college-level studies and the rest largely unprepared for anything else.”

Per Noonan’s experience, and likely that of many others, student accountability and expectations seem to be dwindling,

“My school let students skip assignments and miss deadlines until the end of the semester, then let them do the work at the last minute to avoid a failing grade,” he described. “When I objected, stressing the importance of personal responsibility, the assistant principal replied, ‘Is it your job to teach chemistry or to teach responsibility?’ She didn’t care to hear my answer: ‘Both.'”

Like Noonan, most educators get into the field because they want to help children. When that no longer feels like a priority or even possible in some cases, many will seek employment elsewhere.

How Is the U.S. Trying to Fix the Teacher Shortage?

Entities big and small — from the federal government to individual schools — are trying out different ways to combat the teacher shortage. In Aug. 2022, the Biden Administration unveiled a three-point plan to address teacher shortages:

- Partner with recruitment firms to find new potential applicants

- Subsidize prospective teachers’ training

- Pay teachers higher salaries

To fulfill the first part, ZipRecruiter has launched a new online job portal for K-12 jobs. Additionally, Indeed facilitated virtual hiring fairs for educators and Handshake hosted a free virtual event in October to help current undergraduate students learn about careers in education.

To subsidize training, the White House recommended policymakers use federal funding to establish more teacher-apprenticeship programs. U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona and now former Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh said registered apprenticeship programs in Iowa and Tennessee could be replicated across the country. Last year, Iowa launched a grant program that helps high school students earn a paraprofessional certificate and an associate degree. It also helps current paraprofessionals earn their bachelor’s degree so they can teach — all while gaining first-hand experience in the classroom. The funding covers candidates’ tuition and fees as well as an hourly pay rate of $12 for high school aids and 50% of the wages that districts already pay paraprofessionals.

Walsh said the Labor Department would prioritize the education sector in future apprenticeship funding, including its next round of more than $100 million in grants.

“There’s no reason we can’t have successful apprenticeships in the United States of America; they do it in Europe all day long,” he said.

Education Department Announces 5-Year Plan to Improve Teacher Recruitment, Retention Strategies

More recently, in Sept. 2024, the Institute of Education Sciences, the U.S. Department of Education’s research wing, announced a newly-funded five-year initiative intended to find more effective teacher recruitment and retention strategies for American schools.

“The Center brings together researchers from 10 institutions to study recruitment and retention policies at varying stages of K–12 teaching pipeline across nine states. Researchers will use state longitudinal data systems and analytic approaches to estimate causal impacts of each policy,” the researchers say. “The Center will examine implementation of each policy. The Center will carry out leadership activities designed to bring together key groups involved in K–12 teacher recruitment/retention, to inform the focused program of research as well as supplemental research, share out findings from Center research, and build the field’s capacity to conduct K–12 teacher recruitment and retention research.”

Those policies include:

- Grow-your-own initiatives designed to address shortages of teachers in high-needs districts and increase teacher diversity;

- Financial support to teacher candidates in exchange for work commitments;

- Provision of labor market information to teacher candidates intended to influence their decisions about specialization and job searching;

- Licensure reforms that provide temporary licensure and/or change the cut scores required to pass licensure tests;

- Financial incentives, including salary floor policies, pay-for-performance policies, and financial incentives targeted to teachers in low-income schools and/or in specific shortage subject areas; and

- Teacher working conditions, including the 4-day school week, Advanced Teaching Roles, and working conditions negotiated in collective bargaining agreements.

The participating states include Arkansas, Colorado, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Texas, and Washington.

The latest federal data shows 44% of public schools started the 2022-2023 school year with one or more teaching vacancies. That percentage is even higher for high-poverty schools and those that serve mostly students of color.

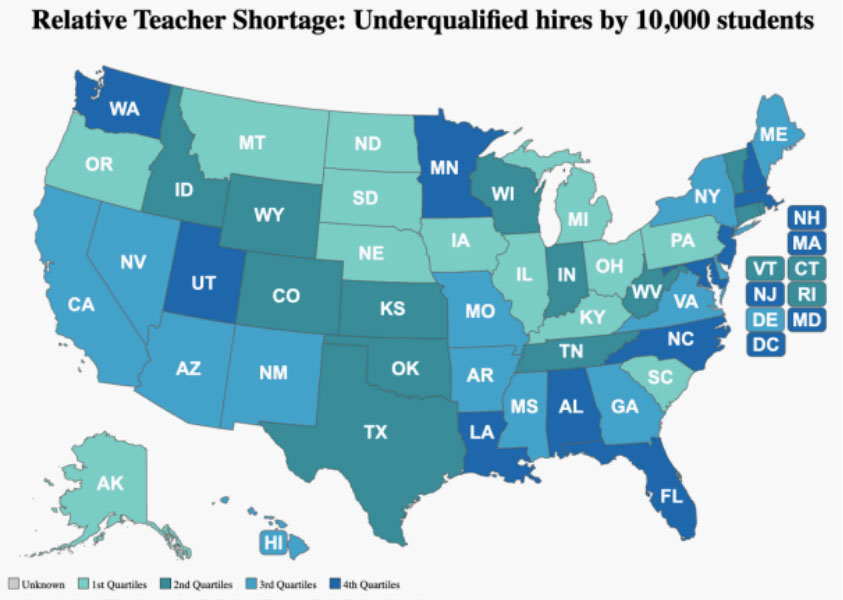

Schools have subsequently lowered employment standards to get positions filled. As of Dec. 2024, nearly 10% of active teachers were underqualified for their position.

Teacher Pay, Mental Health

To pay teachers more, Cardona and Walsh also urged states and districts to use federal pandemic recovery funds. New data shows that on average, teachers make 33% less than other college-educated workers.

“If we’re serious in addressing the teacher-shortage issue, we must first address the teacher-respect issue,” said Cardona. “And that means first and foremost paying our teachers a livable and competitive wage.”

A recent analysis from FutureEd found nearly a third of the country’s 100 largest school districts have increased teachers’ paychecks through bonuses, raises, and college loan forgiveness by using federal pandemic relief funds. Other recent research found that raising compensation does help retain teachers. A study of Florida shortage initiatives found a state loan forgiveness program and a bonus program aimed at teachers in shortage subjects reduced teacher turnover, and annual bonuses of $2,500 were enough to lower attrition among special education teachers.

While paying teachers more helps with turnover rates, the education industry has a higher-than-average vacancy rate of roughly 6%, compared to about 5% across all industries, according to data from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Employees in the education industry also register the most complaints about pay, according to a new USA Today analysis.

Teacher mental wellness is also being taken more seriously. The recent State of the American Teacher survey found three-quarters of teachers reported having access to at least one type of well-being or mental health support in 2023. However, improvements must continue as only slightly more than half said these supports were sufficient. Similarly, the aforementioned RAND report found only half of teachers believe they have adequate mental health support to deal with the levels of stress they are facing post-pandemic.

Districts Shortening School Weeks, States Easing Teacher Requirements

In Texas, the Jasper Independent School District changed to a four-day school week in 2022 to incentivize more teachers to apply for jobs. Since then, nearly 60 school districts across the state have also made the switch. Districts in Colorado, New Mexico, Idaho, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Texas have also moved to a shorter school week. The move to four-day weeks is most popular in rural areas, where districts can save on utilities and cut the miles put on their school buses. About 90% of districts that have adopted the four-day week are in rural areas. The total number of districts adopting the four-day schedule has increased more than 30%, from 650 in 2020 to 850 now, reports EdSource.org.

Some states and districts are responding to shortages by reducing the qualifications to enter the classroom. In 2021, California started allowing teacher candidates to skip basic skills and subject matter tests if they have taken approved college courses, reports EdSource. New Mexico’s Public Education Department decided to eliminate subject skills tests as a requirement for people earning teaching certifications by 2024, according to The Santa Fe New Mexican. Instead, prospective teachers will be allowed to submit portfolios demonstrating their teaching competency.

Oklahoma eliminated its General Education Test as a certification requirement, and Missouri now only looks at a prospective teacher’s grades earned in select courses required to become a teacher. Alabama lowered the cutoff scores for its teacher certification exams. In the state’s Black Belt, there were no certified math teachers during the 2021-2022 school year in Bullock County’s public middle school.

Arizona now allows people without a college degree to begin teaching so long as they are currently enrolled in college. At the beginning of the current school year, schools in Mesa piloted a team teaching model to combat declining enrollment and teacher shortages. At Westwood High School, four teachers instruct 135 students in one giant classroom.

The aforementioned Brown University study also looked at the number of unqualified hires by state, as depicted in the graphic below. The researchers estimate there are 163,000 positions being held by underqualified teachers.

Source: Nguyen, Tuan D., Chanh B. Lam, and Paul Bruno. (2022). Is there a national teacher shortage? A systematic examination of reports of teacher shortages in the United States. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-631).

The highest quartile includes six states in the South, three each for the Northeast and West, and one in the Midwest. Illinois has the lowest number of underqualified teachers at 1.17 positions per 10,000 students while New Hampshire has the highest at 348.79. Notably, New Hampshire has not reported teacher shortage areas to the U.S. Department of Education since the 2019-2020 school year, according to the report.

School Districts Building Affordable Teacher Housing

A 2022 EdWeek Research Center survey found that 11% of teachers said that subsidized housing would make them more likely to stay in the teaching profession. In California, at least three school districts — Los Angeles, Santa Clara, and Jefferson Union — have educator workforce housing development, according to EdWeek. At least 80 other districts in the state have expressed interest in learning more about the process.

In Colorado Springs, Colo., Harrison School District 2 is in the planning stages of building an affordable duplex complex on an acre parcel of land at one of its schools. New teachers have a starting salary of $47,545.

“They ask, ‘Can I live in Colorado Springs?’ And I say you can, but you have to have a roommate or two or three in order to make a paycheck go as far as possible,” said Mike Claudio, assistant superintendent of personnel support services.

Claudio said the units will be net-zero electrically powered homes and rent for $825 a month. Comparatively, the average rent in Colorado Springs is $1,720 a month and the average home price is $523,456, according to Forbes Advisor.

Heather Peske, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), told EdSurge that the relationship between housing costs and teacher recruitment is clear: When teachers can’t afford homes in their school district, it exacerbates teacher staffing challenges. It also hurts retention as teachers who can’t afford to buy a home in their district after 15 or 20 years take their veteran talent elsewhere.

“You lose your skill and capacity in a school when you keep bringing in new teachers who don’t have experience,” Peske said. “When teachers leave, [their] knowledge and skills and the investments districts have made go out the door. The district has to start again with a new crop of teachers.”

Colleges and Universities Working to Improve Shortage

Colleges are trying to do their part as well. A March report from the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education showed that the number of people completing a teacher-education program declined by almost a third between the 2008-2009 and 2018-2019 academic years. In response, Washington, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Nevada, and New Mexico now offer teacher programs at community colleges.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is offering incentives to colleges and universities by only approving new teacher training programs if they involve fields where there are shortages. The Colorado Department of Higher Education is targeting rural shortages by offering $10,000 stipends to teacher candidates who work in rural communities for a year with half the cost covered by the state and the other half by the candidates’ colleges. According to the nonprofit National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), in 2020, Hawaii started paying special education teachers $10,000 more than their peers. In just one year, the initiative drew in 300 new special educators, cutting the shortage by half.

The University of South Carolina is partnering with the Charleston Country School District to use federal COVID-relief aid to train teaching assistants and other school staff to teach math and other subjects with significant job vacancies.

Hope on the Horizon?

Overall, the root causes of teacher burnout and the subsequent nationwide shortage include low pay, increased scrutiny, and poor working conditions. We cannot deny the significant impact these shortcomings are having on educators and therefore the entire education system.

However, there may be some hope as we start to see the impact of federal, state, and local strategies that have been implemented in recent months. The State of the American Teacher survey found a slight improvement in job satisfaction with 23% of teachers saying they were likely to leave their job by the end of the 2023-2023 school year. Of the 77% of teachers who said they were unlikely to leave their job following the 2022-2023 school year, their ability to positively affect students and positive relationships with students and other teachers were the top reasons they intended to stay.

According to NCES’ Feb. 2024 findings, 45% of public schools reported feeling that they were understaffed — a decrease from 53% who reported feeling understaffed the year prior.

Although there has been a slight improvement, NEA President Becky Pringle warns educators are still “exhausted and increasingly feeling disrespected.”

“I call on our policymakers, again, to value our nation’s educators and get serious about solving this problem. That means paying educators like the professionals they are, ensuring that their students can get the mental health supports they need, protecting them from gun violence in schools, and addressing the staff shortages so our educators can do what they do best – help every student thrive,” she said. “Through the pandemic, continued attacks on public education, and an educator shortage crisis, our educators have shown how committed they are to helping their students thrive. Educators need and deserve better. Our students deserve better.”

Curious about how your state is trying to recruit and retain teachers? News Nation Now compiled an impressive state-by-state deep dive. Check it out here.