I’ve previously criticized much active shooter response training, both for officers and citizens, for focusing almost exclusively on response; in other words, what to do upon hearing gunfire and becoming aware of a shooter on campus. That earlier article went beyond the rationale behind the Run-Hide-Fight strategy; it identified the three factors shaping how one selects a response strategy and then how to execute it most effectively.

Article author Lt. John Weinstein will be presenting “Overcoming Obstacles to Innovation” at the 2025 Campus Safety Conference in Austin, Texas, July 21-23. For more information and to register, CLICK HERE.

An integrated approach to active shooter training must recognize all four phases of a crisis: prevention/deterrence, response, mitigation, and recovery. In many ways, the most productive phase of preventing an active shooter is the first. Indeed, the average citizen can do far more than most officers to keep their campuses safe but rarely is given the tools to live up to this potential.

Consider, for instance, an officer driving on the highway while on duty versus off duty. When driving a marked police cruiser on the highways, an officer routinely drives behind the most courteous motorists in the world. However, when off duty in his or her personal vehicle, all manner of crazy, aggressive, rude, and dangerous maneuvers are regularly observed. The lesson is motorists and other individuals usually hide questionable behavior from uniformed officers. As a result, uniformed officers rarely see the behaviors generally seen by campus community members.

Campus citizens can have extraordinary impacts on creating “hardened” campuses by exercising both situational awareness and then reporting what they see. Their vigilance in the “prevention/deterrence” phase alerts a potential shooter that people are paying attention and complicates their chances for a successful attack.

Unfortunately, we tell people to say something when they see something (i.e., concerning behavior), but they rarely do, our encouragements notwithstanding. The reasons are many:

- They are not sure they’ve observed an actual crime

- They don’t want to waste the time of police

- They figure someone else will make the report

- They fear getting involved or retaliation

- They are intimidated by the 9-1-1 process

- They don’t want to “narc out” a friend

- They hope they are wrong or that the problem will disappear

- They don’t want to be accused of being prejudiced or discriminatory if someone of a different race, culture or life-style has caught their attention

- They don’t think the police are capable of addressing the issue

- They fear the police, or

- They simply don’t like the police.

In the absence of reports on concerning behaviors from citizens, the police are destined to see precious little of ongoing or potential wrongdoing and the preliminary cues to potentially deadly attacks. On the other hand, if citizens were active partners and provided police with information on concerning behaviors, timely deterring or mitigating interventions could occur. In time, the campus would develop a reputation a one whose citizens were situationally aware.

This awareness and the light it sheds on potentially criminal activities make it more difficult for potential shooters to surveil their targets and plan their carnage. Situational awareness increases the risk of discovery to the potential shooter, thereby deterring this behavior and effectively making the campus a “hardened” and more secure target.

The empowerment of the campus community to create a partnership with police requires two initiatives: teach campus citizens what types of behaviors to report and convince them to report it. Both initiatives are accomplished through effective campus police/security community outreach programs.

Teaching People What to Report

At my previous institution, we provided campus-wide training on “Recognizing and Reporting Suspicious Behavior.” This training identified potential characteristics (e.g., dress, behavior) of suspicious behavior as well as indicators of concealed weapons, improvised explosives, etc. Most importantly, we reminded the audience that they are not being asked to report suspicious individuals; rather they are asked to report suspicious behavior.

This presentation, along with others on topics like sexual assault, human trafficking, self-defense, active shooters, and more, provided ample opportunity to demonstrate our professionalism, approachability, our desire to hear their reports, explanations of how we operate, citizen safeguards, our commitment to their confidentiality, etc. This outreach made people feel comfortable knowing what to report and how to report it, and they were confident about an appropriate and effective police response. Citizen-police communication increases, making campuses become safer.

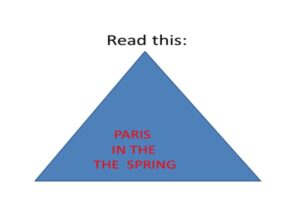

However, before we can convince people to report what they see, we have to train them to recognize what they are looking at. Consider the words in the triangle:

Most people, when asked to read this, see “Paris in the Spring.” They miss the second “the” because they know the phrase and don’t expect to see the extra word.

We use this exercise to describe the difference between “looking” and “seeing” and how the latter is imperative for effective situational awareness. We explain that they missed the second “the” for the same reason they don’t catch typos (absent word check) in their own writings; they don’t expect to see uncorrected mistakes. They are confident everything is OK. In other words, they are complacent.

However, if they are complacent, they are likely to see little. We tell them, referring back to “Paris in the Spring,” that if they expect never to see a weapon on campus, they never will. We also do a drill where arrangements are made with someone in the audience, usually in the back of the room, to get up and leave at a predetermined time. The rest of the audience is asked to describe the person’s height, weight, hair color, clothing, shoes, backpack, etc. Observational skills are noted to be perishable and, more importantly, crucial for effective situational awareness.

So, what are some of the things we teach our citizens to notice? They are:

- Indicators of a concealed weapon

- Unattended vehicles

- Indicators that a vehicle might be holding an explosive device (sagging suspension, certain smells, etc.)

- Indicators of an explosive device

- Dress that is inappropriate for the situation (e.g., a long raincoat in sunny 95-degree weather)

- Behavior that deviates from known baseline behaviors

- Precursors to concerning behaviors.

As noted above, even if people notice concerning behaviors, they often fail to report them. Getting people to report potentially concerning and dangerous behaviors can only be achieved over time by an active community outreach program, consisting of campus presentations, newsletter articles, accessible and friendly patrol, and citizen-police events that promote fellowship, communication, and mutual understanding.

Outreach must address the following reasons, which often explain why people don’t report concerning or unusual behaviors. Under each reason, several counterpoints are suggested to overcome these reasons:

- They are not sure they witnessed an actual crime and they don’t want to waste police time.

- In 2009, a student brought a rifle to our campus and took two shots at a professor in an attempted homicide. (Fortunately, the weapon jammed and the student was taken into custody and subsequently prosecuted and convicted.) We explain that it is not illegal to carry a hockey bag, but doing so is uncommon since the school does not have a hockey team. If the police had been notified of this unusual activity, the shooting might well have been avoided. Campus audiences need to understand that even events that may seem legal may have significant negative and even horrific consequences. Similarly, an unattended backpack may be nothing, but it could also be a bomb.

- Campus audience members are told the police would rather respond to 99 calls that turn out to be false alarms than not respond to the one instance that turns deadly.

- Even calls that result in no serious consequences have a positive impact on campus security because police are seen continuously serving the campus community. People will feel empowered to notify them and expect an appropriate police response.

- They expect someone else will make the report.

- There is a critical role for all members of the campus community to participate in keeping campuses safe and secure. It is not a matter of reminding campus citizens of their obligations but rather discussing how their situational awareness and subsequent reporting empowers them to play a positive role in keeping the campus safe, thereby supporting the college’s academic mission.

- They fear getting involved due to time involved or possible retaliation.

- We discuss how, when, and the extent to which we can provide confidentiality.

- We also discuss the college’s safeguards against concerning behaviors.

- Does an individual’s convenience justify something bad happening to someone else as a result of unreported behavior?

- They don’t want to “narc out” a friend or colleague.

- A recent U.S. Secret Service (USSS) report suggests that timely reporting may be the only opportunity to prevent a disgruntled person or one in need to receive help that makes a positive difference in his or her life. According to the USSS, 100% of the people who commit mass violence were dealing with or had in the past 5 years been dealing with significant stress. This finding is consistent with evidence showing perpetrators of past active incidents had been bullied, had problems in school, suffered romantic disappointments, suffered financial difficulties, had negative experiences with the law, etc. If people had reached out to these individuals, might violence have been averted?

- Employee Assistance Programs, CARE Team processes, mental health counseling, and other college and local resources should be identified as aids for, not punishment of, people in crisis.

- They are intimidated by the 9-1-1 process.

- Explanation of the role dispatch plays and the kinds of information it needs can be presented during outreach, thereby reducing the fear of the process. Tours of dispatch centers are also valuable means of providing information and understanding.

- Outreach can also inform people that they may request anonymity, which also encourages reporting.

- Mobile safety apps often allow anonymous reporting and can be done in a non-obtrusive way. The ubiquity of people always using their cell phones shields the fact that one may be using his or hers to make a report.

- They hope they are wrong and the problem will disappear.

- Hope is not a strategy! Although this response sounds disrespectful, nobody wants to predicate his or her safety on hope.

- Hoping they are wrong is similar to not being certain they have witnessed criminal activity. We train people that if something or someone is out of the ordinary, to report it whether they think it is criminal so we can check it out.

- Intuitively, we know that problems, especially mental needs, feeling of grievance, etc., do not simply disappear or get better with time. People may not report the problem, hoping it will disappear, for the same motivations noted in no. 5 above. The same responses apply.

- They don’t want to be accused of being prejudiced or discriminatory if someone of a different race, culture, or life-style has caught their attention.

- Individuals have stated a reluctance to report people performing certain activities for fear of being labelled racist, a homophobe, an islamophobe, etc. The key to addressing this issue is to note that we do not ask people to report suspicious people; we ask them to report suspicious behavior. Quite simply, it is behavior, such as wearing a full-length raincoat on a 95-degree sunny day that gets an officer’s attention. It is not important whether the raincoat is being worn by a male or female, Black or White, Muslim or Jew, young or old, etc. The fact that the coat could hide a weapon or a bomb is what’s important.

- When an individual speaks to dispatch, dispatch will ask the caller to describe the person. All the person needs to report is the concerning behavior; i.e., why the call is being made. The call is about what; not who.

- They don’t think the police are willing or capable of addressing the issue so reporting is considered futile.

- Most citizens have never heard of a “closure” rate, but they will be surprised to know that most campus police and security departments have very high closure rates because of omnipresent security cameras that identify suspects.

- The bigger issue is the perceived lack of professionalism of campus officers relative to local agency personnel. Campus citizens can learn via various outreach events that campus officers have all the same training and qualifications as municipal and county law enforcement officers, that they often teach firearms, defensive tactics, and other specialty areas to local officers in local police academies, various training they have undergone, significant accomplishments, awards, etc. Most campus departments have a good story to tell about their own professionalism but fail to tell it.

- They fear or don’t like the police. This can be a significant problem on campuses with large international student bodies since in many countries, police are instruments of oppression as opposed to “protecting and serving.” In presentations to international students, over 80% state they have a negative impression of police in their respective homelands.

- We tell audiences that municipal policing is 75% to protect and 25% to serve, but these percentages are reversed in colleges, where the service culture is more pronounced.

- National and state legal and constitutional safeguards should also be explained. Freedoms of the press, assembly, due process, rights against unreasonable search and seizure, rights against self-incrimination, equality under the law, Miranda rights, etc. are non-existent in many countries. When foreign students come to the U.S., they, and even some U.S. citizens, are surprised to learn they have these protections.

- The existence of General Orders, which structure officer behavior; the departmental complaint process; and the independent nature of internal affairs investigations hold officers accountable for their actions and provide additional safeguards for citizens.

- Friendly, helpful and approachable officers, who engage students on foot or bicycles, out of vehicles, can do the most to put once fearful people at home with police officers.

- They believe the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and other information control safeguards prevent reporting and create a risk of liability for so doing.

- Concerns about safety, articulated with reasons and made in good faith, are never against the law or regulation. People need to know that safety and security override these civil and administrative regulations.

Take These Steps Now So Your Community Will Report Threats, Incidents, and Troubling Behavior

Teaching people how to respond to an active shooter is important and cannot be neglected, even though it is highly unlikely that they will ever be the victim of an active shooter. Campuses can deter more concerning behavior and enact timely interventions to maintain safety and security if people know what to report, feel empowered to do so, and actually report concerning behavior. Since first responders rely on inputs from community members to maintain safety and security, it is in the interest of campus police and security officials to play an active role in integrating the community into this culture of awareness.

Briefings and references mentioned in this article are available upon request. Contact the author at [email protected].

NOTE: The views expressed by guest bloggers and contributors are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to Campus Safety.