Editor’s Note: In response to the widespread protests about George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, Campus Safety is reposting this article we ran in July 2018 on unconcious bias.

Original July 5, 2018 article:

The problem of implicit or unconscious bias has been making big headlines recently. In April, two African-American men were arrested at a Starbucks in Philadelphia when a manager called police on them because they hadn’t purchased anything. They didn’t do anything wrong; they just were waiting for a friend. In May, a white Yale University student called campus police when she saw a black graduate student sleeping in a common room of their residence hall. The white student who made the report had to be reminded by campus police that the black student had every right to be there.

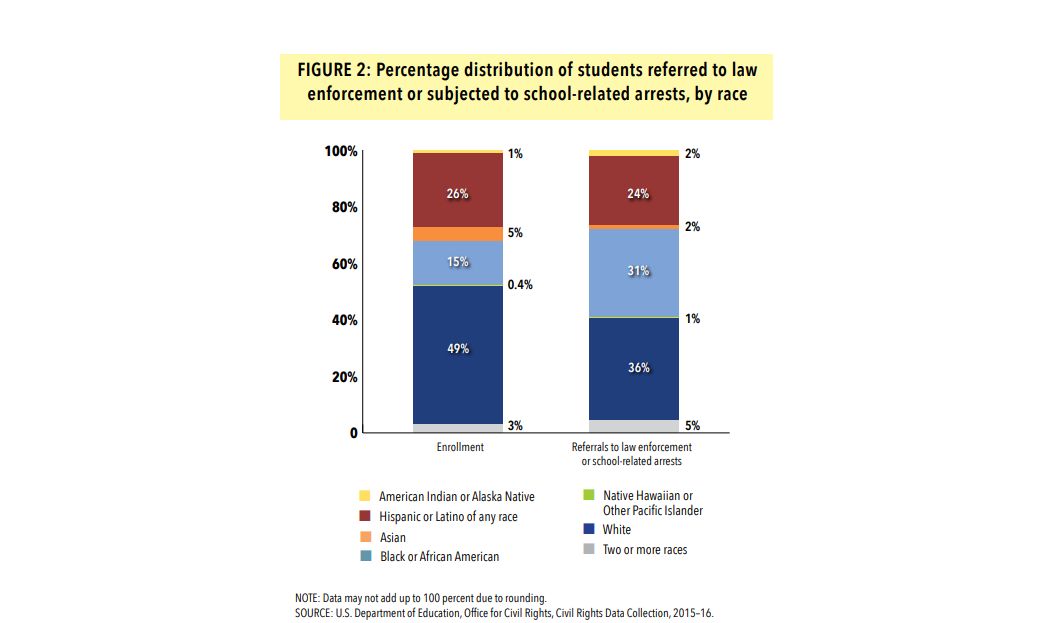

It’s not just black adults who are on the receiving end of bias. K-12 students who are African-American (and even preschoolers) fall victim. This spring, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights released its 2015-16 civil rights data collection on school climate and safety. It found that 31 percent of black students were referred to law enforcement or subjected to school-related arrests despite them only making up 15 percent of student enrollment. Although white students make up 49 percent of enrollment, they only comprise 36 percent of the law enforcement referrals or school-related arrests (see chart.)

There are indications that implicit bias is in healthcare too. According to the CDC, U.S. black women, regardless of their socio-economic status, are three- to four-times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related causes. Some experts believe the disparity could be due, at least in part, to deeply ingrained stereotypes.

I recently saw with my own eyes implicit bias in action. As I was checking into a hotel in April, the receptionist didn’t ask if I was a member of their awards program (I am). I checked in with no problem. After I had completed my check-in, I stepped aside to put my driver’s license and credit card away. While I was doing this, an African American woman who had been waiting in line behind me walked up to the reception desk to check in. I then noticed that the receptionist’s demeanor changed from friendly to very reserved. The receptionist then asked for the black woman’s member number. She didn’t have one, so the receptionist made her get in another line for non-members that was much longer.

Why did the receptionist not ask me, a white woman, for my member number, and why was she so friendly to me but not to the black woman? It sure seemed like a textbook example of implicit bias.

In hindsight, I wish I had fully realized what was happening at the time and said something to the receptionist. I suppose I was thrown off guard, in part, because the receptionist was African American, just like the woman she had targeted with her unconscious bias.

I mention my experience because when we talk about unconscious bias, I think a lot of people (myself included) mistakenly believe it is only a problem for white people. Also, a lot of white folks get defensive about the subject. However, my hotel check-in experience demonstrates that all of us —regardless of our race — have biases we might be unaware of and need to mitigate.

Although unconscious bias awareness is important for everyone in our society, it is particularly so for campus public safety departments. When we witness everyday activities, such as someone taking a nap in the student union, are we attributing ulterior motives to one race that we aren’t attributing to others who do the exact same thing? Are we punishing minority students (as well as students with disabilities) more severely for things like talking back to their teachers or dress code violations?

I doubt it’s possible for humans to be completely self-aware and objective about their thoughts. It’s not easy to admit or even see our own biases. That being said, we all could use more training on this matter.