Over the past few years, sexual assault investigations have been making headlines across the country. From college campuses to military installations, many municipalities and organizations have been under fire for their handling of these important cases. Growing media attention has inspired conversations, studies and the proverbial microscope on these crimes.

Extremely low prosecution rates of sexual assaults were discovered, as well as communication breakdowns between law enforcement, victim advocates, nurses and prosecutors.

Victim advocates sometimes saw the systems and protocols of these investigations chewing up victims and spitting them out. Victims sometimes would not participate or cooperate in the process because they thought the legal system might not believe them. Communication between advocates and Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE) was solely for patient/victim care. Investigators would normally not get involved in that aspect of the case.

Traditionally, investigators would gather facts about a sexual assault case, conduct a victim interview or two, and screen the case with the prosecutor. However, this screening usually only occurred if the investigator believed there was probable cause. Investigators were simply doing what they had always done. We did the best we could with the knowledge and training we had at the time. Some cases appeared to have problems with witness credibility or lack of evidence, and were not prosecuted.

Researchers from a number of colleges and universities collaborated with a few forward-thinking police departments and dug into police reports, court records and prosecutor files to get answers. They soon discovered some disturbing patterns.

Officers initially responding to crime scenes doubted the victims, and seasoned investigators closed cases because they didn’t believe the victims. However, what investigators were seeing were the effects of trauma as the result of sexual assault… trauma that law enforcement personnel interpreted as lying.

So, here’s what we did in Utah.

Police Try Out New Process for Interviewing Sexual Assault Victims

The Salt Lake County (Utah), Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) was already organized and conducting regular meetings. Missing, however, was the regular involvement of law enforcement. Once a few detectives from various agencies got involved, however, the team began to hit its stride. Communication and networking were key. New and exciting changes began to occur.

RELATED: How Title IX Complaints are Handled by the OCR

Investigators began to train together. I attended a breakout session on the neurobiology of trauma taught by Donna Kelly who is now the Salt Lake County assistant district attorney. Fireworks went off in my head, and the gaps in my cases suddenly started to fill in. Shortly after that, the guilt set in because I knew I had not done right by the brave individuals who disclosed what happened to them, only to have me close their cases.

I felt the guilt of knowing that I was previously patrolling my community and not understanding what was happening on calls involving trauma from sexual assault as well as other crimes, such as domestic violence calls, robberies and vehicle crashes. I felt horrible thinking I might have booked several people into jail who shouldn’t be there. I began to study, search the internet and go to trainings around the country on my own dime to see the experts instruct. But something that appeared to be missing was an outline on how to conduct an interview.

The experts at the event I attended were sharing excellent information, however, as a career cop I needed a simple tool to follow. I understand bright colors and four letter words. I needed a short, simple, flexible outline to refer to during an interview. I reached out to Kelly and asked if there were one out there. She made phone calls around the country to the individuals we had seen present. At this point in time (2013), we were unable to locate such a tool.

Kelly had experience during her career in Oregon developing the child interview process. She suggested we try to do something similar for sexual assault. Honestly, we couldn’t screw up these cases any more than we already had been. SART member Dr. Julie Valentine, who is a professor and researcher at Brigham Young University, signed on to study the effectiveness of what came to be called the “Trauma Informed Victim Interview” (TIVI) process after getting full Institutional Review Board approval to do so through her university. Approval was also obtained by West Valley City Police Chief Lee Russo to conduct the study. Our study was only conducted with adult victims of a sexual offense.

Detectives Change Their Approach to Sexual Assault Victims

We started the TIVI study by changing a few processes and then trained the detectives who were going to conduct the interviews and investigations. One of the most important processes to be changed was patrol officer response to the initial case. The new process began with a brief interview on scene with the victim to establish probable cause that a crime was committed, locate evidence and witnesses and identify a suspect. Then a call was made to the investigators for direction.

A delayed interview was set up at the station in a comfortable interview room. The only exception to the doing the delayed interview was if a domestic or intimate relationship existed. Domestic violence victims were interviewed in a trauma-informed way on scene. We used this approach for domestic violence victims because they are the least likely to follow through with the system once police officers leave the scene for myriad reasons I won’t get into now.

At interview time, we requested and encouraged the victim to let a victim advocate be with them during the interview. This formed a bond with the advocate that helped keep the victim involved from report to court. Then we began the interview process, which I’ve separated into three phases.

The 3 Phases of the Victim Interview Process

Phase 1: Set the Tone — We set the tone of the interview by explaining to the victim the roll of the investigator and the victim advocate. Then the investigator explains that the purpose of the interview is to gather as much information about what happened as possible. We tell the victim that it’s important to share everything. We tell her or him that we understand some things might be difficult to talk about, might be difficult recalling and might be painful. Sometimes we might need to ask hard questions, but before we do, we’ll explain why this information is important. It’s also OK for the victim to say “I don’t know.”

Phase 2: Listen to the Victim — Phase 2 is the hardest part of the process because we have to shut up and listen to the victim’s full account of what happened. It’s important not to interrupt the victim’s narrative. A flood of information will begin to come out, much of it you don’t need for your investigation. Despite this, shut up. Your job as an investigator is to sort through this narrative and find the gold nuggets. The appropriate time to ask questions is towards the end of the narrative, and you’ll know when that is. Narratives have been known to go from ten minutes to an hour. Patience is also key. Using silence as a tool, we begin to ask sensory and feeling questions around the event — that moment during the incident when consent was no longer part of the interaction between the victim and suspect— as well as other traumatic events that occurred.

Phase 3: Explain the Process — During this phase, we advise the victim how to communicate with their investigator and advocate when they leave. For example, I don’t respond well to phone calls, but if a victim emails me, I respond quickly and sometimes when I’m off duty. Communicating via email also provides a record of questions and emotions they are feeling. I then explain the process and the estimated time the system takes in this area. I don’t make promises about outcomes, but I do let them know that I will try my hardest for their case.

It’s also critical that all cases with a known suspect be taken to the prosecutor for screening, even the ones we believe do not have probable cause. In some cases, prosecutors might suggest follow up and then file. Even if the case is not filed, investigators should follow through with all of their leads. Offenders are often serial in nature, and these cases could show a pattern on the next report.

Results of the TIVI Approach Are Promising

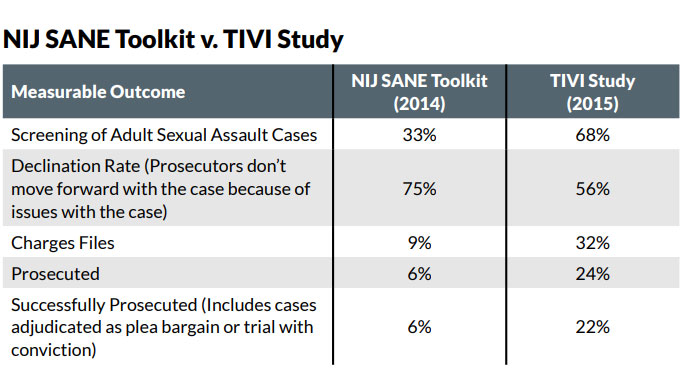

Before the Trauma Informed Victim Interview (TIVI) study, Dr. Julie Valentine completed a study in Salt Lake County using the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Toolkit on criminal case outcomes. The NIJ SANE study examined criminal case outcomes in adult sexual assault cases in Salt Lake County from 2003 to 2011 with a collection of sexual assault kits. West Valley City Police Department numbers were consistent with those found across the county. These were cases that had sexual assault kits completed. The TIVI study included all reported adult cases in West Valley City. During the study year, 64 cases were reported with approximately 75 percent currently adjudicated. Although not a large number, the results of the TIVI approach were extremely encouraging. (Some of the results comparing each approach can be found in the NIJ SANE Toolkit v. TIVI Study chart below)

Just as impressive are the numbers reflecting the survey questions asked of the investigators and victims during the process. In one year there was a slight culture change in the attitudes of the investigators, showing what can happen over time. Anonymous surveys from the victims indicated that they felt heard, validated and believed. Regardless of the criminal case outcomes, helping victims to heal through our interactions and the interview process is critically important and helps a victim become a survivor of sexual assault.

There are two ways to think of this process of investigating sexual assaults for the victims. I like to define this as “system justice,” where the victim is treated with respect, believed, listened to and the case is fully vetted, however not filed. Then there is the “justice system” where the case is prosecuted successfully and the suspect is sentenced. Both are extremely important for the victim, who is now a survivor.

This process is not fast. In fact, this process takes more time in a system and culture that is not set up for it. Change is hard, but it is necessary, and above all it’s the right thing to do.

Justin Boardman has been an officer with the West Valley City (Utah) Police Department for 14 years and is a member of the Salt Lake County sexual assault response team. Along with Salt Lake County Assistant District Attorney Donna Kelly and the Utah Prosecution Council, he coauthored a trauma informed victim interview protocol for adult victims of sexual assault.

Read Next: How Colleges Should Respond to Sexual Assault Reports